Ocean Liners: Speed and Style, currently on view at the Victoria & Albert Museum, brings the luxury, modernity, and romance of traveling by sea during the 20th century. While the exhibition covers all aspects of ocean liner travel, including décor, promotion, and engineering, I was particularly struck by the room detailing Life on Board. Life on Board features a stunning array of cruise-wear ranging from the turn of the century to the late 1960s. The show gives room to show everything from high-end couture worn by first class passengers in the 1920s and 1930s to bikini’s worn by the deck pool in the 1960s. This broad range gives a comprehensive overview of golden age ocean liner fashion in the 20th century, and the changes to life on board as the century progressed.

As you enter the ‘Life on Board’ room a screen with an ocean scene creates a ship deck ambiance. The pool-side scene featuring bathing suit looks from different decades is set against this blue sky and sea backdrop. A mannequin languidly lounging behind the “pool” sports an Emilio Pucci bikini from 1968. The bikini has been styled with large, white sunglasses and a matching headscarf. The pattern, of different shades of blue and aqua, and accessories give the mannequin a distinct, almost psychedelic, youthful 1960s glamour. Sitting next to the Pucci-clad model is a more conservatively dressed mannequin dipping a toe into the pool. She is dressed in a Jantzen one-piece bathing suit from the 1950s. In between the two seated mannequins is a standing mannequin wearing a bathing top and shorts made by Viking in the mid-to-late 1920s. Finally, the mannequin in the very front is placed to look as if she is diving head-first into the pool. This athletic mannequin is clothed in a two-piece yellow bathing suit from 1937-39. The contrasts between the different colours, eras, and styles of bathing suits gives a broad sense of life on deck throughout the golden age of Ocean Liner travel. The reclining and active mannequins placed against the blue-sky background allowed me to feel as though I were truly witnessing a poolside scene on the deck of a grand ship.

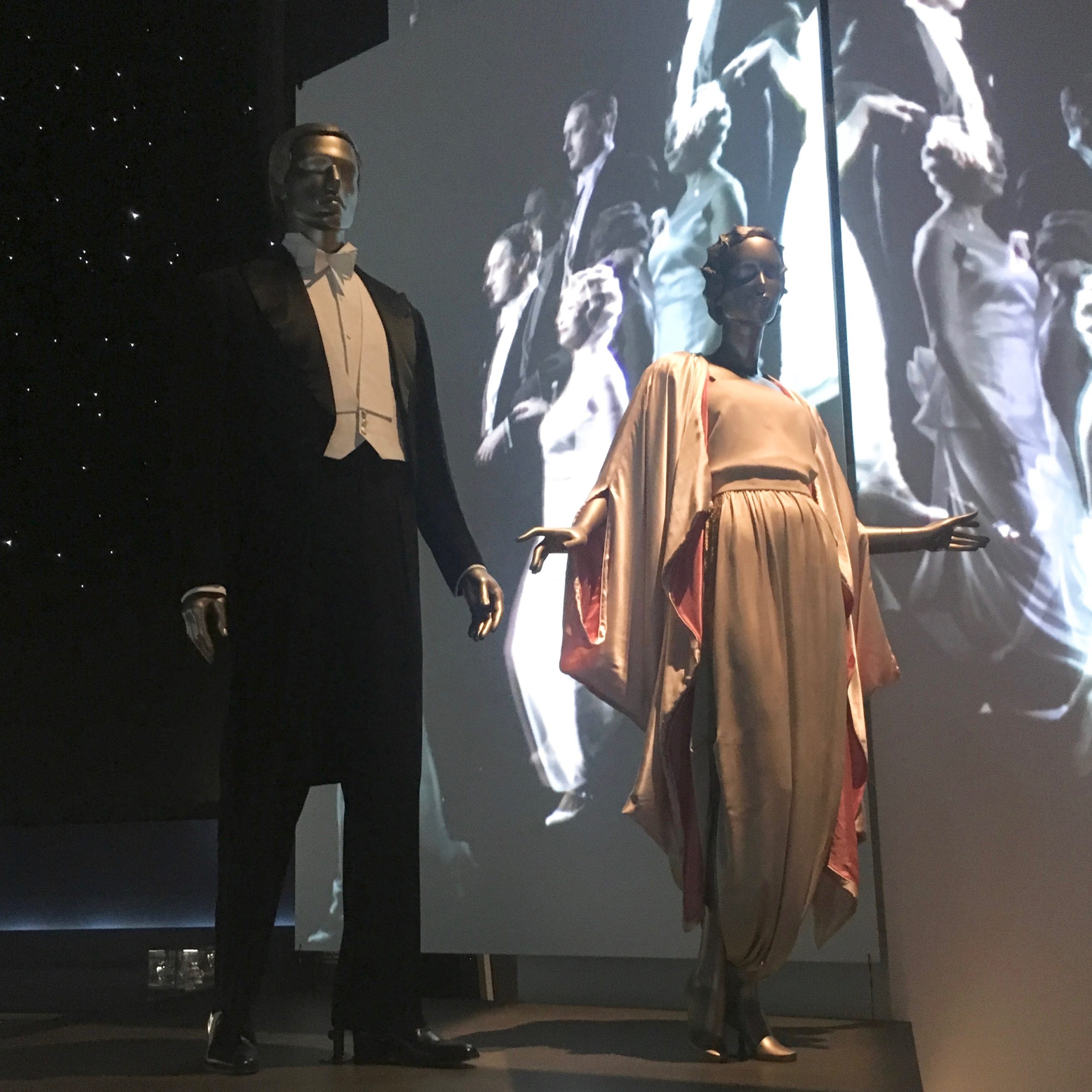

On the opposite end of the spectrum, displayed directly opposite the pool-side scene, is a re-creation of the Grand Descente. The Grand Descente was an elaborate staircase that led into the dining room, from which fashionable first-class passengers could make a memorable entrance and show off the latest fashions. The staircase is recreated as a series of plain back platforms elevated one above the other. The austerity of the staircase in the exhibition allows attention to be drawn to the garments. Behind the mannequins is a screen, onto which, a procession of models in gowns is projected, thus giving the sense of movement associated with the Grand Descente to the still mannequins. The ceiling above the display is black with countless small, lights, giving the appearance of a glittering, glamourous night sky. The mannequins display three gowns worn by New York socialite Emilie Grigsby in the 1910s-1920s, and a men’s evening ensemble worn by US Diplomat Anthony J. Drexel Biddle Jr. The outfits all enhance the glamorous image of ocean liner travel in the early 20th century.

Ocean Liners: Speed and Style does an excellent job of comparing and contrasting clothing from different decades and different occasions. By placing elegant 1920s couture across from bikinis from the 1960s, the viewer gains a sense of how much ocean travel changed during the course of the 20th century, but how it remained a glamourous endeavor.

Ocean Liners: Speed and Style is on view at the Victoria and Albert Museum until June 17th.

By Olivia Chuba

All photos taken by the author