As the dissertation deadline looms, we’re spending some time getting to know the current MA Documenting Fashion students. Simona discusses growing up in her family’s fashion boutique, dress as a language and American screwball comedies from the 1930s.

Do you have an early fashion memory to share?

I have many early memories related to fashion. I often say that I was born among clothes: my grandfather started his textiles business in the south of Italy in the 1950s, which he shortly after turned into a menswear boutique. My father started working there at the end of the 1970s and then opened his own boutique in 2000, when I was just four years old. The boutique still exists in its original location and is currently run by my elder siblings, with the support of my father. I have many memories related to both my grandfather’s and my father’s businesses. As a child, I was extremely fascinated by the tactile qualities of clothes: I particularly loved passing my hand through the suits, perfectly hanging on their display racks, organised by colour, cut and fabric, and unfolding every shirt, sweater and pair of trousers to look at their smallest details, often deciding to try them on despite the obvious size mismatch. Some of my favourite memories involve a game I used to play in the boutique, where I would pretend to be a sales assistant with the support of our oldest employee, who would kindly and patiently play along, interpreting the role of ever different customers with the most bizarre requests. It was certainly good training – also because he taught me how to fold every item properly.

What is one thing you’ve learned about dress history that you wish more people knew?

That dress history in itself is not just about ‘clothes’. The general understanding of the concept of dress is so shallow that trying to explain to those who ask what it means to study it is quite complicated. I recently came across a picture in a fashion magazine with a text reading ‘I don’t understand what my clothes mean’, and I became obsessed with it. It made me think that this is precisely the reason why I decided to study dress history: to understand the meaning of these items that we put on our bodies – along with all the elements that compose our appearance – which possess a unique and incredible communicative power, even more immediate than words. The problem, however, is that this language is unknown to most people, and trying to decipher it without the right tools is practically impossible. Studying dress history gave me those tools, unlocking an immense universe which encompasses multiple fields, such as sociology, social anthropology, psychology, economics, and politics.

What is your favourite thing you’ve read this year?

Every paper or book I read thanks to this course was fascinating and challenging in its own way. However, to go back to what I was saying before about not knowing what the concept of ‘dress’ actually means: I would say one of the most important things we have analysed, at the very beginning of the MA, was Joanne B. Eicher and Mary Ellen Roach-Higgins’ ‘Definition and Classification of Dress: Implications for Analysis of Gender Roles’. As a long-time supporter of Judith Butler’s ideas on gender as performance, this paper furthered my understanding of how, in the societal context I am writing from, the most prominent social distinction communicated by dress is that of learned gender roles.

What is your dissertation about?

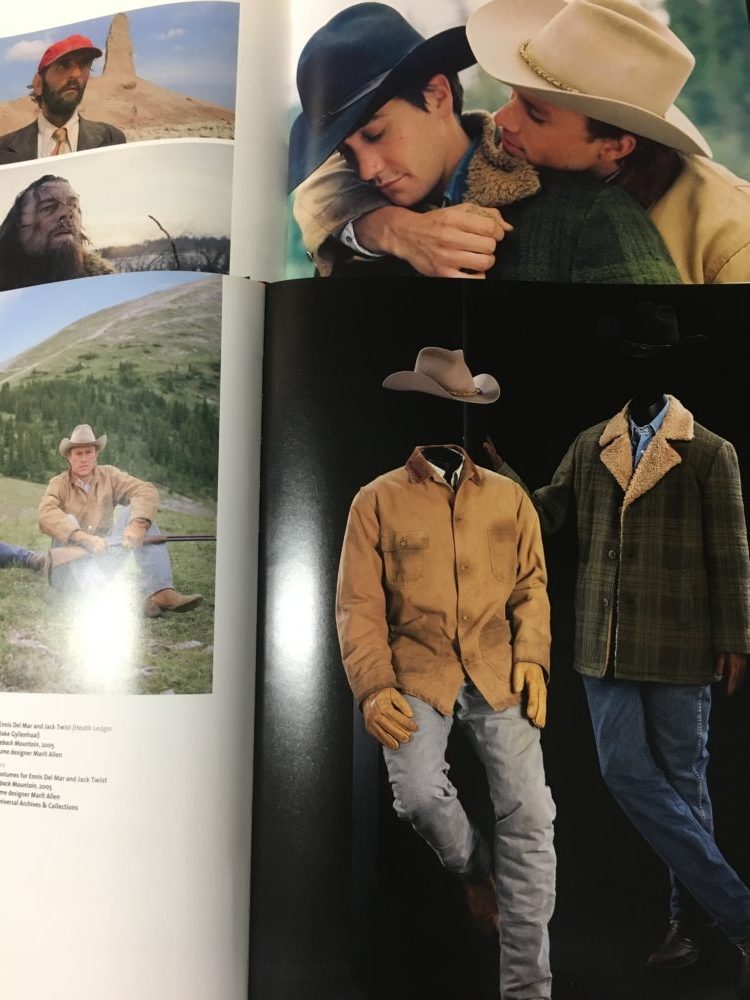

My dissertation is about the intersection between star image, costume design and film genre. I am discussing the function and meaning of costumes in the context of the American screwball comedies of the 1930s, through a specific focus on the screen couple Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant in Howard Hawks’ 1938 movie Bringing Up Baby and George Cukor’s The Philadelphia Story, released in 1940. Throughout my academic career, I have been particularly interested in star studies and how this field relates to film and fashion. I wrote my undergraduate dissertation on Sophia Loren’s costumes in Vittorio De Sica’s 1963 comedy Ieri, Oggi, Domani, and, although through different lenses, I enjoyed the idea of following a similar path to conclude my MA. Comedy is one of the richest and most fascinating genres, in my opinion, and I believe there is much to be said about the implications of clothes and fashion when it comes to screen comedies.

Which outfit from dress history do you wish you could wear?

This is such a hard question! I will go with the one outfit that immediately came to my mind when I read this question, which is included in one of my favourite portraits and dress history images: Charles Frederick Worth’s evening ball gown worn by Empress Elisabeth of Austria, Sissi, in her 1865 portrait painted by Franz Xaver Winterhalter. It is just sublime. The off-the-shoulder neckline, the white satin mixed with tulle, with thousands of silver foil stars shimmering throughout the dress, matching the diamond edelweiss pins in her long, braided hair… I must have dreamt of a dress like this a thousand times in my childhood ‘princess’ fantasies, way before I became acquainted with this painting. Plus, what an unforgettable experience it would have been to be dressed by the father of haute couture himself!