When one speaks of Stanley Kubrick, what comes to mind is often the world-renowned director’s timeless oeuvres as A Clockwork Orange (1971), Barry Lyndon (1975), The Shining (1980) and Eyes Wide Shut (1999). And yet, Kubrick’s brilliance was evident even in his often overlooked teen years, when he was just starting out in his career behind the lens, with photographs taken in the streets of New York.

At the mere age of 17, a young teen from the Bronx, Kubrick traded in life as a student after graduating from high school, when he was discovered by Look magazine and hired as staff photographer in 1946. Thus began his brief yet fruitful career as a photojournalist which in many ways paved the way to his stepping into Hollywood and becoming of a filmmaker.

1940s was the time of photo narratives/stories which had surged in popularity with Life magazine. A rival of Life, Look magazine’s aesthetic was focused on the everyday rather than the events of the globe. It aimed to convey the intimacy, eccentricity, and ordinariness of life in New York City. The city’s dynamism, chaos and its multiculturalism made it the perfect location to base the photographs and stories for which it was a source of endless entertainment. Kubrick’s photographs taken for Look between 1945 and 1950 are a reflection of the golden age of post-war America and boom of capitalism. The palpable energy of the city is very clearly translated to the viewer while the style of Kubrick in capturing everyday life reminds one of film noir, a genre he favoured in his films as well.

Kubrick’s career in Look, which ended in 1950 when he decided to leave the magazine behind to focus on making feature films, encompass over a thousand photographs by the famous director. They were often named as being proto-cinematic that signalled to his talent with the camera and unsurprisingly, interest in filmmaking. Although this talent was strongly nurtured during his time in Look that gave Kubrick the opportunity to focus on human interactions and how it could be reflected through the camera it is evident that he was already a naturally gifted storyteller. His genius in conveying the psychological depth and emotion of his subjects through the lens clearly shows through his adeptness at handling the camera, setting and framing scenes to push his narratives, which all formed the strong foundation for his filmmaking career.

‘Everyday’ in New York City that Kubrick captured with his camera encapsulated ordinary people in parks, subways and stores to TV and Hollywood celebrities going about their lives. Kubrick’s ability to turn the ‘everyday’ and ‘ordinary’ into a visual story, and a compelling one at that, was evident early on. Although many of these photographs were spontaneous instances from everyday life, many of them were staged, which also perhaps nodded to Kubrick’s passion for storytelling and interest in film. Kubrick was given assignments, shooting scripts to construct and align his photographs/photo-essays accordingly. He also presented his own themes which were often accepted by the magazine. The given narratives strengthened the filmic quality of Kubrick’s photographs.

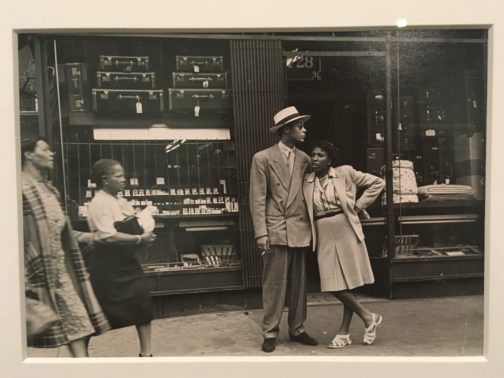

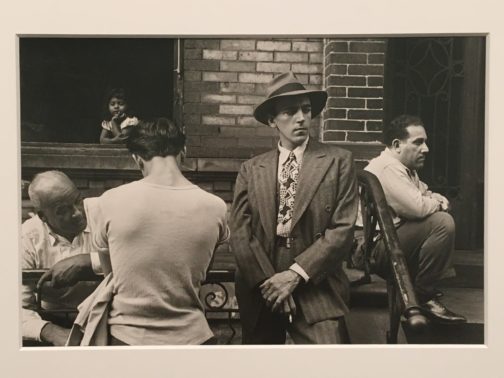

One of the main themes of Kubrick’s photographs was genuine human interactions embedded in daily life. His series for the 1946 November issue of Look feature photographic sequences from the street titled Bronx Street Scene: The Camera Catches an Off-guard Episode over a Hairdo. In a series of photos shot consecutively, two women are first seen chatting in front of a shop which is then followed by another shot that show the entrance of a passer-by, another woman into the frame and the two women fixing her hair and having a laugh over the matter. A different strip shows a couple smoking and chatting on the street in front of a store. The naturalness of the gestures and facial expressions coolly emanate from the frame, mesmerising us and insinuating that we have caught glimpses, instances from life with these people and watching from afar in a discreet manner. The consecutive shots and usage of the same vantage point here that reveal the continuation of these two different events very clearly refer to filmic techniques.

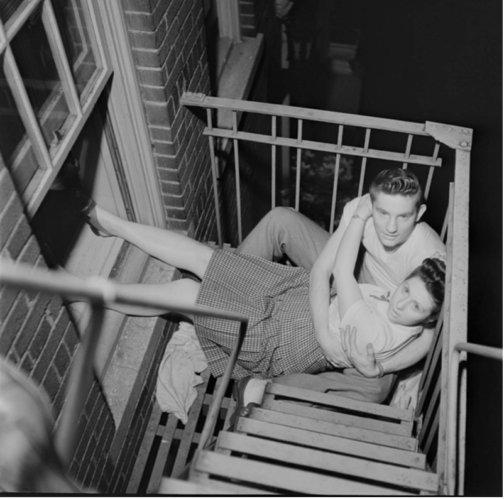

Kubrick caught spontaneous scenes from the street. Some he turned into scenes with consecutive shots as seen here. Others instead, were single shots that entailed an overarching theme, such as Park benches: Love is Everywhere series created in 1946 for May 1st issue which was a love series where Kubrick captured young couples on benches, fire escapes and street corners, embracing. Kubrick’s usage of infrared film and flash intensified the candidness of the scenes. The couples were often seemingly caught in unexpected moments, especially at night-time, similar to paparazzi shots which highlighted the voyeuristic tones that Kubrick’s photographs often carried, resembling the technique that was frequently used by famous tabloid photographer Weegee.

A Couple Embracing on a Fire Escape is one of the most unique shots in the series that seems to have a sinister undertone. With not only the oblique angle, the awkward positioning of the couple on the fire escape but also the overpowering flash that has overly whitened the eyes and skin of the couple, transforming them into ghostly figures, reminiscent of deer caught in headlights, which speaks to Kubrick’s genius with the play of light.

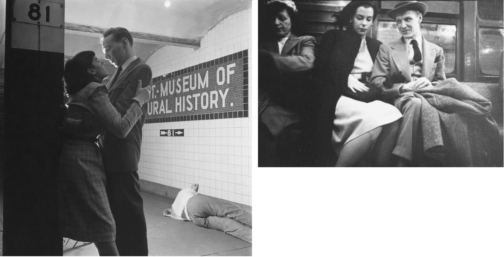

The New York subway offered a microcosm of the city. Spending time at the subway for almost two weeks, Kubrick shot discreet photos of people riding the subway with a hidden camera for another assignment titled Life and Love on the New York Subway in 1947 that fit the everyday life of New Yorkers narrative. Placed amongst the candid photographs in the subway spread, some of the photographs such as this one that show a couple, in fact Kubrick’s friends Alexander Singer and Toba Metz, sleeping, were argued to be staged. While the low vantage point, the dramatic contrast between black and white made scenes as the photograph with the couple embracing cinematic, it also put forward the harsh realities of big city, with the homeless man sleeping in the background, somewhat taking the focus away from the romance in the shot.

The shots that focus on individuals and their facial expressions show a study of psychological depth that also belongs to the cinematic verse. Glorifying the normalcy of everyday life of ordinary people in the big city stretched from photographing people waiting in line to do laundry, waiting in the subway and shopping in the city. What all of them shared in common was the focus on large crowds to highlight the act of looking. We see people watching other people and then we realise we are also watching these people through Kubrick’s lens.

This theme was made central in a series that Kubrick had created, capturing in separate ‘reaction shots’, the confused and surprised expressions of people watching a publicity stunt with a model triumphantly posing next to a group of sign painters in front of a billboard for a Peter Pan bra advertisement high up on a building on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street (September 3, 1947). In this collaborative work with Frank Bauman and Tom Weber, Kubrick’s interest in film became more poignant, whilst also showing that entertainment and spectacle were always around the corner in an ordinary day in New York City, embedded in the spirit of the city.

In another series for Look, Kubrick started to focus on individual profiles. In this spread he celebrated the balancing act of a young shoeshine boy named Mickey, documenting a day in his life. Son of Irish immigrants, Mickey made a living by shining shoes to support his family. Taking around 250 photos for his first long photo-essay assignment, Kubrick presented the young boy’s life, showing him playing and conversing with friends in one shot, working, doing laundry, or contemplating life in a mature manner on a rooftop of a New York building in the next shot. Showing Mickey’s difficult life stuck between trying to provide for his family whilst simultaneously trying to enjoy his young years, Kubrick poignantly captured the difficulties faced by lower classes in attempting to survive in a thriving, chaotic city. The fact that this series was not published shows that gruesome realities of a big city were mostly glossed over in Look compared to Life. This photo series that contrast shots of Mickey with friends and ones where he is wandering the city alone poignantly intensify the difficult double life he leads, both, juggling adult responsibilities.

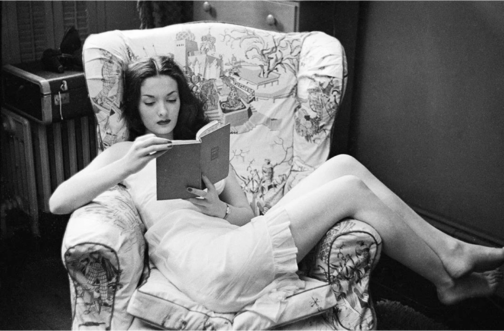

Edging closer to his interest and career in film, Kubrick’s photographs after 1948 started to focus on well-known faces from TV and Hollywood. Kubrick offered the most psychologically complex portraits from these people’s lives. One series that showed the disparity between public persona and private, backstage reality, was another ‘unpublished’ photo narrative series from March 1949, where Kubrick captured a day in life of a showgirl named Rosemary Williams. Williams was a young girl that had come to New York City dreaming of becoming an actress.

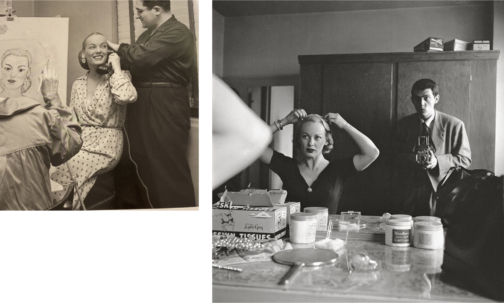

However, struggling to make ends meet as an ingénue in the big city, Williams became a showgirl by night to attempt to make it as actress by day. It was evidently a far less graceful lifestyle compared to that of an actress, as Williams often performed in revealing clothes for the pleasure of men. Captured walking in the streets of New York, having coffee, reading in the privacy of her home to posing in front of the camera and in the backstage getting ready to go on stage, Williams’ life is documented in around 700 images, amounting to one of Kubrick’s longest narratives.

Her professional life is shown through shots of her either conversing or dancing with men or posing in front of the camera. These photographs that show her with company, emphasize the overpowering male gaze that is directed on Williams that signal to her profession and the tool that allows her to sustain her dreams in the big city. Kubrick captured Williams’ despair resulting from the hardships she faces perfectly in her demure expressions and often contemplative manner, from moments of leisure when she alone appears within the frame, much like the aforementioned Mickey. Perhaps the most intriguing photograph of Williams is the in-between public and private realms, where she is getting ready in the backstage in front of a mirror before her performance. Yet, Kubrick haunts this scene with a menacing stare and manner, with a camera in hand which is strategically lowered as he looms large behind Williams as she carries on preparing for the stage, seemingly unaware. Insinuating the voyeurism of the male spectator and the life of a showgirl – which is one that is under constant scrutiny of the male gaze due to the exhibitionist nature of the profession – is perfectly reflected here not only with Kubrick’s sinister placement at the back, intensely staring at Williams getting ready, but also with the mirror and the camera that appears to be subtly filming her below vantage point. Undeniably eerie, the genius of Kubrick lies in the blurring of the concept of the gaze. Perhaps a reference to Velazquez’s Las Meninas the subject of the photograph also becomes the viewer. The viewer is caught in the act of watching Williams in a private moment. Williams is caught between a crossfire of gazes as the camera directed to the viewer reminds us that we are also active voyeurs. The widened frame and the surrounding sense of mystery contributes to the filmic elements of this scene. It becomes evident that the running theme of the ‘unpublished’ spreads were harsh and forsaken reality of the city that Kubrick attempted to unearth and present to the wider public in the manner of Life magazine yet one that was often hindered by Look. This perhaps became a further push for Kubrick in the direction of cinema where he could tell his stories freely.

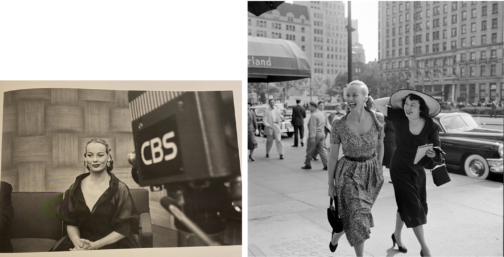

Look magazine also differed from Life in the sense that it aimed to show the ‘real’ lives of Hollywood and TV figures to instil the sense of normalcy around famous people, showing them both on and off camera. Yet, Kubrick still offered heavily staged photographs. Williams’ story was most likely swapped for a high-profile celebrity spotlight issue on Faye Emerson titled, Faye Emerson: Young Lady in a Hurry. Emerson was considered as picture of elegance, grace and intelligence. TV was on the rise and was slowly becoming a rival to radio and print. A Hollywood actress recently turned in to TV presenter, Emerson was regarded as ‘First Lady of TV’ and listed under ‘Top Female Discovery of 1949’ list, which, alongside her career switch, made her worthy of a cover story according to Look magazine. Emerson in this photographic series created by Kubrick for the August 1950 issue, is presented as joyful, both behind and in front of the camera: whether she is distributing autographs for eager fans, interviewed near the Plaza hotel, captured having a laugh with the society columnist Eleanor Harris, casually sitting for a portrait with a phone in hand making calls whilst also getting her hair done.

Emerson never ceases to smile in the photos despite her evidently busy schedule, forming part of Kubrick’s constructed story surrounding Emerson, promoting the busy yet elegant and content lady to aspire to, which the title clearly insinuates. In one photograph, Emerson is captured whilst getting ready in her dressing room. Kubrick uses the same style and framing with the mirror he used in the unpublished photograph of Williams backstage, placing himself behind Emerson with a camera, watching her whilst she’s getting ready. Yet the difference here is that Emerson is aware of being photographed by Kubrick and almost poses for him whilst getting ready to be on screen. Usage of a mirror cleverly conveys the duplicity of TV personas, and their elaborate yet fabricated self-creation for TV.

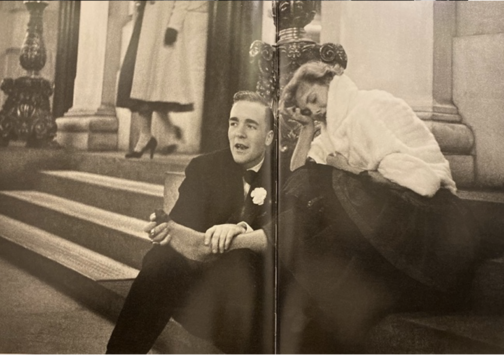

Very similar to Emerson’s profile was one created for Betsy Von Furstenberg. Furstenberg was the daughter of a German aristocrat and was also as an actress in New York. Another, ‘Day in the Life of’ piece, her everyday life was represented in a cinematographic and theatrical way in these photograph series by Kubrick. She is shown engaging in a variety of ‘serious’ and normal activities such as preparing for a role in her home, socialising with friends as well as silly moments from peeling a banana in a fancy restaurant to sleeping on the steps of the Plaza hotel next to John Hamlin. These pictures were featured in Look magazine’s spread from July 18, 1950 with the title The Debutante Who Went to Work. Photographs represent the juggling of day-to-day life with a highly glamorised one with comedic effect, evident from the awkward moments, humorous gestures, and facial expressions of Furstenberg. Whilst a more psychologically in-depth narrative was worked on for the earlier photographs of Williams was ultimately shelved, favouring a feature that was created around a lady that worked despite her aristocratic background.

Very similar to Emerson’s profile was one created for Betsy Von Furstenberg. Furstenberg was the daughter of a German aristocrat and was also as an actress in New York. Another, ‘Day in the Life of’ piece, her everyday life was represented in a cinematographic and theatrical way in these photograph series by Kubrick. She is shown engaging in a variety of ‘serious’ and normal activities such as preparing for a role in her home, socialising with friends as well as silly moments from peeling a banana in a fancy restaurant to sleeping on the steps of the Plaza hotel next to John Hamlin. These pictures were featured in Look magazine’s spread from July 18, 1950 with the title The Debutante Who Went to Work. Photographs represent the juggling of day-to-day life with a highly glamorised one with comedic effect, evident from the awkward moments, humorous gestures, and facial expressions of Furstenberg. Whilst a more psychologically in-depth narrative was worked on for the earlier photographs of Williams was ultimately shelved, favouring a feature that was created around a lady that worked despite her aristocratic background.  This shows the elegant façade that sought to represent life in New York City, with the gruesome realities of hardship were kept very deliberately hidden. A debutante that balanced life and work was one to be aspired to while a showgirl trying to make ends meet was one that was far too real and far less glamourous. Von Furstenberg’s story was about elegance, and, on the surface a light-hearted, innocent story of how to make it as an actress in the big city, despite being further removed from reality. The theatricality of the mimics and gestures of Von Furstenberg is in high contrast with that of Williams which almost insinuates the fabricated nature of this narrative and lifestyle.

This shows the elegant façade that sought to represent life in New York City, with the gruesome realities of hardship were kept very deliberately hidden. A debutante that balanced life and work was one to be aspired to while a showgirl trying to make ends meet was one that was far too real and far less glamourous. Von Furstenberg’s story was about elegance, and, on the surface a light-hearted, innocent story of how to make it as an actress in the big city, despite being further removed from reality. The theatricality of the mimics and gestures of Von Furstenberg is in high contrast with that of Williams which almost insinuates the fabricated nature of this narrative and lifestyle.

Looking back at his brief time as a photojournalist in 1972, the director himself commented: ‘By the time I was 21 I had four years of seeing how things worked in the world. I think if I had gone to college I would never have been a director.’ Photographs such as these taken in the streets of New York put forward the theatricality of the city which Kubrick presented in his characters, personas and well-known faces that made up the city, delving into private lives of public figures, producing intimate and psychological portraits. Whether watching these figures from afar, standing in the crowd beside them or even in their private quarters, Kubrick always placed the viewer in the intimate world of his subjects. The photographs offered a genuine image of New York City, shining light on different lifestyles of those from a variety of backgrounds, showcasing moments that revealed the everyday routines of people from different classes, with everyone united in their common goal of attaining ‘The American Dream’.

Looking back at his brief time as a photojournalist in 1972, the director himself commented: ‘By the time I was 21 I had four years of seeing how things worked in the world. I think if I had gone to college I would never have been a director.’ Photographs such as these taken in the streets of New York put forward the theatricality of the city which Kubrick presented in his characters, personas and well-known faces that made up the city, delving into private lives of public figures, producing intimate and psychological portraits. Whether watching these figures from afar, standing in the crowd beside them or even in their private quarters, Kubrick always placed the viewer in the intimate world of his subjects. The photographs offered a genuine image of New York City, shining light on different lifestyles of those from a variety of backgrounds, showcasing moments that revealed the everyday routines of people from different classes, with everyone united in their common goal of attaining ‘The American Dream’.

The director’s final film Eyes Wide Shut (1999), set in New York, caused quite a stir in its exploration of the mysterious and dangerous sides of the vibrant city of New York, focusing on an elite cult. This suggests that the famous director was perhaps making a nostalgic tribute to his time as a young photojournalist in the midst of this chaotic city he found himself in, and the vibrant scenes he caught glimpses of with his camera as a teenage boy. Today, Kubrick is better known for his 12 feature films yet his strength in visual storytelling was implanted in his little-known early career as a photojournalist. It is evident that for Kubrick these early photographs, as Sean Corcoran (the Photography Curator at the Museum of the City of New York) stated, allowed him to master the art of framing the composition and opened his eye in different ways of seeing. Kubrick himself said: ‘Generally speaking, you can make almost any action or situation into an interesting shot, if it’s composed well and lit well.’ Kubrick’s genius seeps from his œuvre produced in his short time as a photojournalist, right on the brink of his career as a director.

The director’s final film Eyes Wide Shut (1999), set in New York, caused quite a stir in its exploration of the mysterious and dangerous sides of the vibrant city of New York, focusing on an elite cult. This suggests that the famous director was perhaps making a nostalgic tribute to his time as a young photojournalist in the midst of this chaotic city he found himself in, and the vibrant scenes he caught glimpses of with his camera as a teenage boy. Today, Kubrick is better known for his 12 feature films yet his strength in visual storytelling was implanted in his little-known early career as a photojournalist. It is evident that for Kubrick these early photographs, as Sean Corcoran (the Photography Curator at the Museum of the City of New York) stated, allowed him to master the art of framing the composition and opened his eye in different ways of seeing. Kubrick himself said: ‘Generally speaking, you can make almost any action or situation into an interesting shot, if it’s composed well and lit well.’ Kubrick’s genius seeps from his œuvre produced in his short time as a photojournalist, right on the brink of his career as a director.

By Ipek Birgul Kozanoglu

Bibliography

Albrecht, Donald; Corcoran, Sean. Through a Different Lens: Stanley Kubrick Photographs, (Köln & New York: Taschen, Museum of the City of New York, 2018)

Mather, Philippe D. Stanley Kubrick at Look Magazine Authorship and Genre in Photojournalism and Film. (Bristol:Intellect, 2013)

https://museemagazine.com/culture/2018/7/31/exhibition-review

https://www.mcny.org/exhibition/through-different-lens

https://ny.curbed.com/2018/5/1/17305690/stanley-kubrick-photos-museum-of-city-of-new-york-exhibit

https://edition.cnn.com/interactive/2018/06/entertainment/stanley-kubrick-cnnphotos/