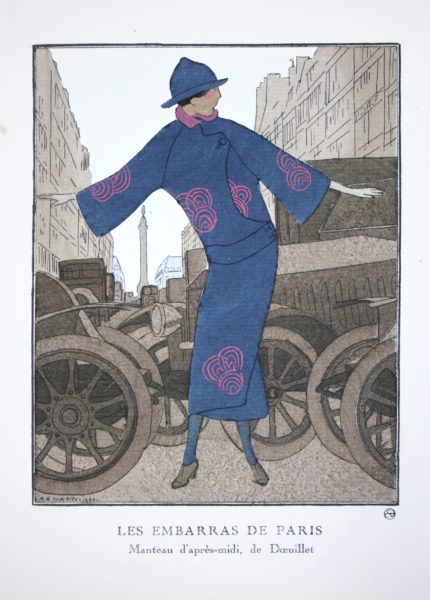

How does your environment affect the way you dress? Of course, there’s the weather to be taken into consideration. But what about the type of place that you live? For example, are we shaped – literally and figuratively – by urban dwelling? Does the city impact not just the type of clothes we choose, but also how we feel when we wear them? Living amongst huge numbers of people, coping with the speed of street-life, the fleeting encounters with our fellow citizens … surely this impacts our psychology, our way of being, and therefore our way of dressing?

These are not new questions, German sociologist Georg Simmel published an essay in 1903 and updated in 1950 entitled, ‘The Metropolis and Mental Life,’ which tackled just such concerns. At the core he argues, is the constant tension between individuality, and being part of society. What is at stake is the ways we adapt (or don’t) to these twin desires/pressures. Of course, Simmel was writing at the start of the 20th century, but many of his ideas remain relevant, and suggest the subconscious issues brought to bear on our daily outfit choices.

Or as Simmel puts it in relation to the ‘psychology of metropolitan individuality’ – which is founded upon: ‘the intensification of emotional life due to the swift and continuous shift of external and internal stimuli.’ Even crossing the road means experiencing multiple sights, sounds, and encounters with people and machines.

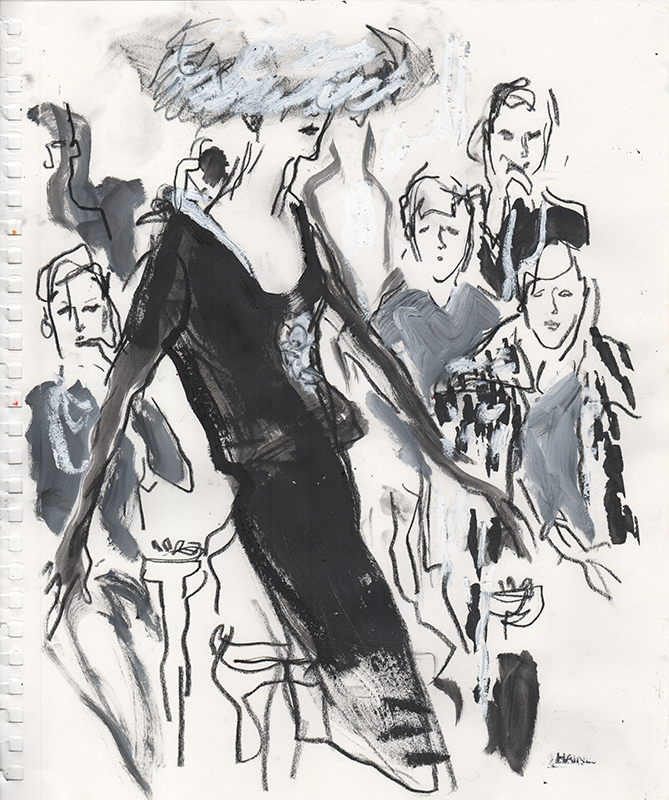

And this must be considered in relation to our brief interactions with other humans in much of daily city life, as well as the money economy that distances consumer from producer. This means that the counter impulses to be hyper-individual and to assert your sense of self, versus the desire for a protective shield of conformity and anonymity are likely to influence how we dress. It makes you think again about the ubiquitous male suit – is it in part saving city workers from the ‘violent stimuli’ Simmel identifies as part of urban life? Does it reinforce his argument that city dwellers must react rationally, rather than emotionally – creating a protective sartorial barrier between themselves and the city?

What is produced, he says, is a blasé attitude that tempers the dissonance that surrounds us. Simmel sees this as a rich site for mental development, despite its problems. And clearly, the Metropolis is equally rich for the development of multiple fashions as well. Just as the suit-clad banker assimilates, so designers and wearers can experiment and create in response to the city’s speed and excess of stimulation.

By Rebecca Arnold

You can read Simmel’s essay in full here