As another academic year draws to a close, I want to reflect on the wonderful time I have had teaching my Class of 2019 MA Documenting Fashion students…

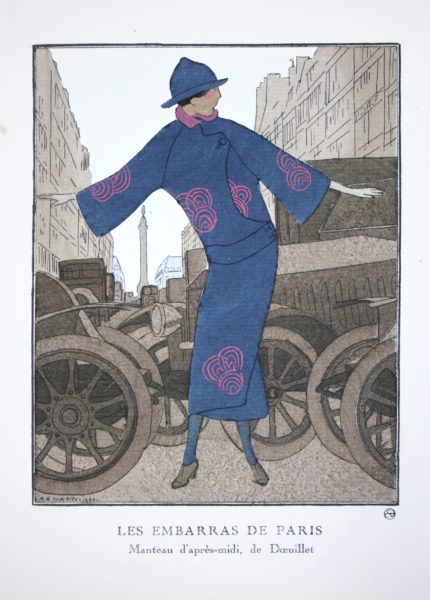

The autumn term started with a breakfast to greet my new students—and it was clear what an interesting and sparky group they would be. During the initial thematic classes, we discussed what the terms ‘dress’, ‘fashion,’ ‘costume’, etc. meant and looked at a range of books in our Special Collections—from a 1598 edition of Vecellio’s Habiti antichi, et moderni di tutto il mondo to Paul Iribe’s beautifully illustrated Les robes de Paul Poiret of 1908, to consider the ways fashion has been documented and represented through history.

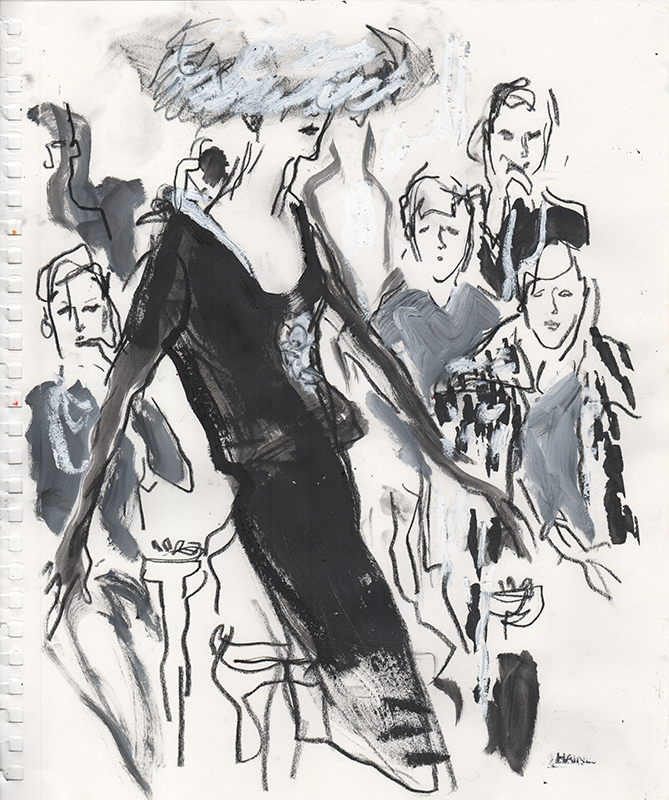

We talked about our sensory experiences of fashion, fashion’s relationship to memory—personal and historical—and visited archives to develop our ideas. This included a trip to see Beatrice Behlen, Head of Fashion and Decorative Art at the Museum of London, where she showed us several people’s wardrobes; there, the group was entranced by the ways individual style can be recognised and analysed in any era.

And this was just the opening section of the course and of the students’ entry into the world of Dress History. It has been so rewarding to see all of you develop from this point—increasing your already considerable skills and finding exciting lines of enquiry as you developed your dissertation topics.

So, thank you Daisy, Ellen, Fran, Imogene, Jeordy, Lacey, Lily and Marielle—you have all been a complete joy to teach, and I am really looking forward to seeing what you do next. Enjoy the summer—get some well-deserved rest and relish your success at The Courtauld.

Please join us Friday 29 June, 2018 at the Courtauld Institute of Art 10:30am-12:00pm for a live recording of The Conversations with Jason Campbell & Henrietta Gallina podcast, open to all free admission

Please join us Friday 29 June, 2018 at the Courtauld Institute of Art 10:30am-12:00pm for a live recording of The Conversations with Jason Campbell & Henrietta Gallina podcast, open to all free admission