Each month in 2015, we will post an interview with one of our alumni, as part of our celebrations of this year’s auspicious anniversary. The Courtauld’s History of Dress students have gone on to forge careers in a diverse and exciting range of areas. We hope you enjoy reading about their work, and their memories of studying here.

Alumni Interview Part Two: Harriet Hall, Courtauld Institute of Art MA (2011).

Harriet Hall is a freelance journalist specialising in Art, Fashion and Entertainment. She has published work online and in print, as is currently working on a book about the history of Sportswear. Harriet also works for the BBC, producing segments for live radio and television, and has interviewed celebrities, designers, artists and industry experts.

Could you tell us a little bit about what you are up to now?

I am a journalist. I work three days a week at the BBC News Channel as a producer, and three days freelance, writing Fashion and Art pieces. I am currently writing a fashion book for Bloomsbury on the history of Sportswear. I give myself Sundays off!

Did the MA course help you to progress to where you are today?

Absolutely. The course provided me with knowledge of how to analyse and write about dress, and a historical grounding that I apply to everything I write. It made me realise I was allowed to take fashion seriously. It also introduced me to many people across the world of fashion and dress, most of whom I am still in touch with. It’s important to have a network of close friends and colleagues you can turn to for advice and vice versa.

You graduated from the Courtauld in 2011. Could you describe the structure of the course back then?

It was the first year that Rebecca Arnold taught the course (although I’d stupidly spent the pre-application time reading Aileen Ribeiro’s work, which was a century earlier!) so it was great, because we were all new; we were all starting a journey together. The course focused on the inter-war period in Paris, London and New York. It was all very liberating and chic. I wrote mostly about feminism- Virginia Woolf and then for my thesis, the Japanese Lolita – I missed the memo about keeping a tight focus!

Would you say that the History of Dress Department, with such small numbers (alongside fashion’s undeserved association with ‘triviality’), was seen as inferior in any way?

I never found at the Courtauld that anyone looked down on anyone’s subject – academic importance was afforded to everything, because the word Art is so all encompassing. They wouldn’t include it at the university if it wasn’t considered important. We were, as a class, a little separate from the other students, but that just made us all a lovely tight-knit group.

Are there any memorable highs and lows of the course that you’d like to share with us?

The high point was definitely going to New York on a study trip. We went behind the scenes at some of the most prestigious museums and met all the curators, and did lots of shopping! Low point – returning from New York to revise for our exam a week later. Jet lag and libraries aren’t a great combination.

Did you come from a fashion background or was it something new to you?

I studied History of Art for my BA, so it wasn’t entirely removed. I had always considered studying straight fashion design or art, but I wanted to know about everything that had come before, how it was received and how it was built upon. I was always obsessive about fashion, reading about it at every moment, collecting Vogue and spending all my money on clothes, so I felt perfectly at home studying it – it never felt like something new to me.

Did the Courtauld succeed in paving the path to a career in fashion? How important do you think a fashion-specific degree is to a job in the industry?

For curator roles, the History of Dress MA is virtually a requirement, but for my career it has been more of an invaluable addition. In journalism, many people expect you to have done a more vocational degree but for me, I think the historical and analytical knowledge is far more important, you learn the rest on the job.

Could you talk a little bit about your career path since leaving the Courtauld? Any mistakes, any triumphs?

I started by interning at the Victoria & Albert museum, where I worked in the fashion department as a cataloguer and, separately, alongside a curator on a display of Japanese Lolita dresses. It was great timing with my thesis, and I was able to speak alongside him at the museum and at Hyper Japan events. Afterwards, I interned at Marie Claire, and later secured a job as Features Assistant at InStyle the January after I graduated. I worked at InStyle for a year. After I left InStyle, I began working at the BBC, whilst writing freelance Art and Fashion reviews for various publications. Soon the BBC promoted me to become a Broadcast Assistant on the news, and someone asked me to write a fashion book at the same time!

There have been some difficult moments, working in the media isn’t an easy path, and you’ve got to be prepared to stay at home a little longer. I’ve had to hold myself up with part time work – at a hairdresser and a beauty salon, and write a lot for people for free, but it’s important to prioritise building up a portfolio, first and foremost.

Did extra curricular activities and networking with peers and alumni have an impact on your academic life?

I didn’t really have time for much else other than researching for the course, but I would say that developing friendships and bonds with the other students was invaluable. We helped each other through everything – from advice on topics, to essay stress-outs and even sharing our photocopier money! It’s important to realise you’re all a team, not individual competitors. I made friends for life.

Could you talk a little bit about the sportswear book you are working on?

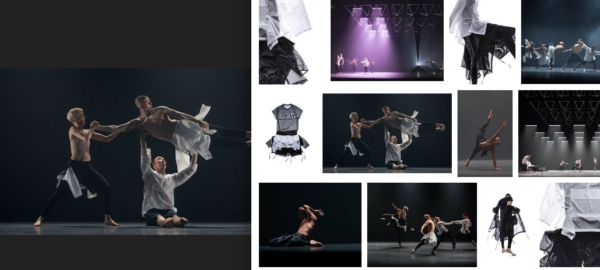

It charts the history of sportswear from the 1900s to present day, focusing on specific designers as milestones. I am writing it alongside sportswear designer, Christian Blanken, who is going to illustrate it. It’s a brilliant time, because sportswear is more popular now than ever, and it’s such a versatile, liberating style of dress. It’s going to be a coffee table book- big and glossy with lots of great pictures. It should be ready for publication at the end of 2016- so that’s what everyone’s getting for Christmas next year.

Do you keep up to date with the Courtauld’s events, exhibitions and publications?

I keep my eye out to see how the new classes are going and have attended a few lectures – you feel somewhat connected to the people on a similar journey to you. And of course I keep in touch with my peers and Rebecca. I think the History of Dress blog is great.

If you could own one exquisite piece by any designer (dead or alive) what would it be?

I love the black feather dress from Alexander McQueen’s Autumn/Winter 2009-10 ‘Horn of Plenty’ collection – it looks impossible to wear but it’s magnificent – although I don’t know if the birds were killed or not, so maybe the red cape and white gown from the Autumn/Winter 2008-9 ‘The Girl Who Lived in the Tree’ collection – it’s so regal. Of course, I don’t think I’d get away with them down the local…

What is your dream project/achievement/job?

To author a book (nearly there), to produce and present my own fashion programme and to be editor of Vogue one day. (aim high, I say.)

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve been given?

Comparison is the thief of joy. I try to hold onto that because in every walk of life there will be someone younger, more intelligent and more successful than you, and you just gotta get over it. Also, don’t let the bastards grind you down.