“You are always switching from disappointment to love and despair to admiration”

Elisa De Wyngaert graduated from the Documenting Fashion MA in 2014 and now works as a fashion curator at the MoMu Fashion Museum in Antwerp. In between, she worked for Raf Simons and A.F. Vandevorst, reviewed fashion exhibitions on the Belgian radio, and in the evenings gave guided tours of exhibitions at MoMu. I spoke to her about her career trajectory, her curatorial process, and her valuable advice on pursuing a career in the history of fashion.

JH: How was your time at the Courtauld, and how did it lead to where you are now?

EW: Before the program, I did my MA in Belgium in art history. At that time I wrote a dissertation on fashion and was looking for some guidance or for someone to teach me how to do academic research on fashion not just from a classical art historical viewpoint. I wanted to do another MA and it took me quite a long time to find the Courtauld and decide. It played a very big part in the way I think about the subject, which really shaped my approach to fashion studies and the way I create now. You reflect in a very different way on fashion—it’s academic, it’s sociological, it’s cultural history, but it gave me more than that. I think it is also very much about the emotional and personal layers of dress and sensorial experiences; it is a completely different way of thinking about art and fashion and it gives you time to develop your thought process and challenges you which was good. The Belgian University system is very different: the professors will teach you, you study books and books of information and then you will take an exam where you repeat everything they told you, but Rebecca is very different. She doesn’t just teach, but she enables you to teach yourself and that is something extraordinary. I remember the first few classes I was like ‘I want her to tell me everything she knows!’ but that isn’t the point. The course was very instrumental.

Right after I graduated I was mourning a bit, I was like ‘this is what I love but how will I ever do something that even comes close to this experience in the next years!’

JH: I’m feeling that right now! It is a scary thought really.

EW: It is a scary thought and I empathize with you and your fellow classmates. I felt very alone when I came home in that there was nothing like it and no one to reminisce with. I didn’t find people with similar experiences when I returned and no one knew where I could work. I applied to different fashion companies and they all understandably said ‘but what do you want to do here?!’

JH: How did you then transition to curatorial work? I think that is kind of the dream for a lot of us.

EW: The previous question is important to this, if you graduate and you hope to immediately find your dream job for you, your personal dream, then it is so easy to be incredibly disappointed. What I did—and it wasn’t easy to do—was that I went to work in a multi-brand shop, a few days a week, and half of the time I was doing an internship at Raf Simons. After a while I really needed full time paid work and started at A.F. Vandevorst where I worked on logistics, wrote newsletters, worked in the flagship store, packed boxes. It was very hands on, but in the evenings I gave guided tours at the fashion museum in Antwerp, and I also worked for the Belgian radio as someone who reviewed fashion exhibitions.

It is very important to make the transition, there are not so many jobs, and it is important to stay busy. It was also important for me financially to go and take a job rather than wait and write letters at home, and to have colleagues that I formed close friendships with. It can be an incredibly inspiring time even if it isn’t a job you will do forever. You will learn from everyone you meet on a personal and professional level.

I have to say working in a fashion house wasn’t the job for me but I learned so much from A.F. Vandevorst. I have so much respect for designers and their work ethic, for what they create, and I think by working for a fashion company, as a curator now I have much more empathy. If I ask for loans at different fashion houses, I realize that they have a different schedule, that they are so busy, their timing is different and their deadlines are different and it’s good to have insight into an industry when you work on the more academic side.

Work on different aspects of things you want to curate, learn and have fun in the meantime. I never thought I would find a job as a curator but all of a sudden I saw I could apply and I was almost sad, thinking “there is a position and I won’t get it,” so it also takes a bit of luck and serendipity and right timing. Don’t give up!

JH: I am interested in your curatorial process. During class we spoke to someone at the V&A about their curatorial process but I’m curious to hear more about how you choose exhibition subjects and how you get something approved and to the point of starting work on a show.

EW: We have to find a balance between designer exhibitions and thematic shows. The thematic shows especially lead to new ideas for future exhibitions. I like these because you can display a large variety of artists and designers and it allows you to work in an interdisciplinary way. Fashion is intrinsically linked to emotion, to society, to the world in transition, to people’s psychology and I feel there is a lot more to tell and the ideas seem endless, but it’s important to discuss these topics with external voices with different iterations, different viewpoints. I have learned that curation is more about listening than about speaking, it is more about including different voices, realities, perspectives, and you have to get used to the fact that you can find something interesting or relevant but other people might not feel that way.

JH: I’m just curious, when you were at the Courtauld did you have the virtual exhibition as an assignment? What did you do yours on?

EW: Yes – I did mine on the friendship and artistic symbiosis between Ann Demeulemeester and Patti Smith. I made an exhibition about sound and clothing coming together and it was very immersive (although it never actually happened haha). It was quite conceptual and I am still happy about it, I’m still hoping it could happen one day!

JH: That for me was a lot harder than the essay writing for some reason!

EW: Ah! That for me was the least stressful part, I discovered that I always thought I loved writing so much but I actually get such a thrill from making visual connections and finding new and personal stories so I am perhaps at my core more of an exhibition maker than an academic or a writer. I also love working on the publications for our exhibitions, getting all the texts from the different writers, focusing on some essays myself and finding the right images. It is kind of thrilling seeing things materialize, and that is something I learned from being on the fashion house side. I did really like the virtual exhibition but as a non-native English speaker I found writing that first essay rather scary.

JH: Are you working on anything now (that you can speak about)? Obviously we are in such a unique time, I don’t know if you are working on a project now and how the virus has impacted your work and how you think it might continue to impact the fashion industry and your cultural institution.

EW: We are now closed for renovations until 2021. I am working on the new collection display—this will be a new space where we focus on MoMu’s own collection. This is great because in our thematic or designer exhibitions there is not always a lot of space for our own collection, and we do have so many amazing pieces. We are also working on a book about the collection, and I am working on our opening exhibition and its accompanying publication. All very exciting!

JH: A lot of stuff!

EW: Also I’m on Rebecca’s Fashion Interpretations Network which is so inspiring.

When it comes to the crisis, we are mostly working from home, we are lucky in that we were closed for renovations anyway so we haven’t felt like we missed tickets or visitors as other institutions have, but I really do feel sad for other museums, galleries, universities, and art schools. Mostly for the students and artists who saw exhibitions cancelled, students who traveled from all over the world to get a degree somewhere, spent so much money on it, and now see everything stop. I really believe that our generation and the younger generations, gen z, are great activists and they give me hope for a better world and a better fashion industry, more woke cultural institutions, but there is so much work to do. I try to think ‘ok what I’m doing is not saving the world but how can we help, how can we make it relevant or in some way meaningful to some people’ because fashion is a very difficult industry, it is so damaging in so many ways but also so relevant, emotional, omnipresent, innovative and inspirational. You are always switching from disappointment to love and despair to admiration.

JH: Definitely, even just as a student I agree, I find myself thinking—especially being back in the US at the moment and things are really bad—I feel the same kind of ‘oh how can I be focusing on this niche subject when this is going on in the world?’ but I think art and fashion and the humanities will always be important and relevant.

EW: Like you say it is so important and I keep my fingers crossed that the government keeps investing money so that artists, performers, musicians…can be supported.

JH: I guess just a frivolous question to end on but do you have a favorite piece in the archive for any reason?

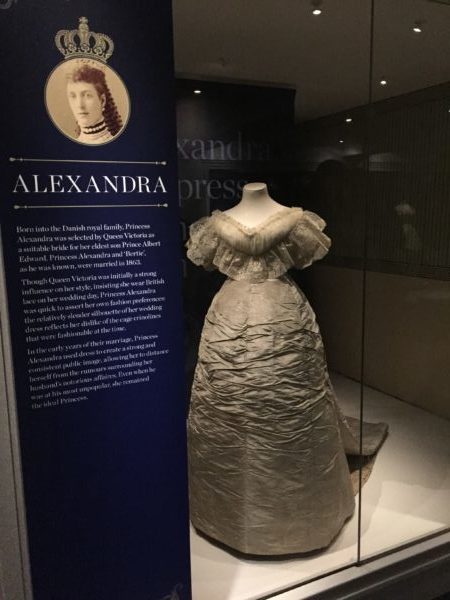

EW: Oh, many. I really like all the pieces we have in the archives that we collected from the wearer. As a museum we actively acquire pieces from designers so we will shop straight from the runway—those pieces are incredible but never worn, but I do really like it when we collect it straight from the wearers. If you collect it from someone and you also collect that person’s biography, their lived experience. For example there is one dress from Kristina De Coninck, a former model of Martin Margiela. It’s a flower dress that Margiela made especially for her, and it’s composed of many recycled vintage flower dresses that he collected from flea markets—it’s like a patchwork. The colors are beautiful, it’s quite see-through. We have a picture of her when she was in her early twenties wearing the dress in her garden, and I was able to interview her. Perhaps in 50 years some curator will think ‘oh, there is a story with this dress,’ and that excites me.

I really like all the garments that we have that display a typical Belgian surrealism. We have quite a few items created from discarded fabrics and recycled materials. For example, a beautiful bustier top by Ann Demeulemeester that she made with very simple hotel soaps which is incredible. We have an A.F. Vandevorst skirt made with corset closures, it is intriguing, and we have pieces by Walter van Beirendonck made of old blankets. When you see them up close you see the fun the designer had, the passion, the originality. These objects make me happy and give me a lot of belief in why fashion is relevant and not a frivolous thing, and why it is something that will always have a future as long as we believe in the next generation and don’t drown in nostalgia.

JH: I think I can kind of speak for the current cohort but it is such a scary time for us to be graduating and looking for work so it is really nice to hear from you and about your experiences.

EW: I often work with people doing part time internships who have other jobs on the side, I do remember it is not easy, but even if you intern for 2 or 3 days you can make it work. I think having those discussions when you apply and being very open about your options just for the sake of own mental health is important. Internships are really crucial because only then do you really learn which job would suit you personally. For example, fashion curating entails a lot of emails, conversations, loan agreements, production logistics, excel sheets, trying to find pieces. I find it all exciting, but I can imagine that some people expect it to be all research or library work and that is only a part of what I do.

There aren’t that many jobs as a fashion curator in a traditional museum but there are so many experimental galleries, new small niche publications, online platforms to get experience from, so be open to different forms of curating fashion. What Rebecca is also doing on her Instagram is curating fashion.

Students now have incredibly curated Instagram feeds, how we engage visually with the world changes so much. I find it incredible how much things have changed even just since I graduated.

[This interview has been condensed for clarity]