Lesley Miller is Senior Curator of Textiles and Fashion at the V&A and Professor of Dress and Textile History at the University of Glasgow. She has led the curatorial team on the reinterpretation of the Europe 1600-1815 Galleries at the V&A over the last five years, and returns to her duties in Textiles and Fashion in 2016. Her current research projects focus on early modern dress and textiles.

Your first degree was in Hispanic Studies at the University of Glasgow, before you went on to pursue the History of Dress for an MA at The Courtauld. What led you to Dress History? How was the transition; did any interesting connections arise between the disciplines?

The sewing skills I learnt as a child provided the route into historical dress studies while seasonal treks around remnant shops and department stores handling materials laid the foundations for my knowledge of textiles. As a student, I spent my summer holidays making costumes for either theatrical performances or museum displays under the guidance of my mother. Penny Byrde’s book The Male Image alerted us to the existence of the Courtauld course. I was not optimistic that I had the qualifications – no history or art history at undergraduate level. But, I did have more than two modern European languages, and they have proved invaluable throughout my career. Initially, at the Courtauld, having come from a language and literature background without an image or an object in sight, my visual memory was extremely poor. A daily diet of dozens of slides at the Courtauld, a weekly diet of visiting art galleries and the Witt Library’s rich photograph collection soon had its impact – and I am still grateful for that exhilarating training.

What was the History of Dress course like when you studied at The Courtauld?

The History of Dress course was still a two-year programme in 1980 under Aileen Ribeiro’s stewardship: the first year was a survey from the classical world to the present day; the second comprised a special subject – in our case, ‘Dress in England and France, 1740-1790’ – and a 10,000-word dissertation on a subject of our choice – in my case, on men’s dress in Golden Age Spain. The 18th-century course provided my entrée into a PhD on 18th-century French silk manufacturing, while my dissertation put dress into the Golden Age drama I had studied at undergraduate level before I had any inkling of what the plays might have looked like on stage. That research also allowed me to understand the paintings and sculpture I had seen in art gallery, church and street in Castile during the time I had lived there, and the impact they might have had on contemporaries. At the end, I knew that I wanted to pursue research to PhD; that I didn’t want to work in a museum; and that teaching was how to share my newfound passion.

How did your time at The Courtauld make an impact upon you? Can you tell us about your PhD at Brighton University?

The Courtauld Institute and Brighton University were poles apart, the former a small, specialized monotechnic with an exclusive focus on art history (and conservation), quite precious in many ways and isolated from the wider University of London geographically and socially (those were its days at Portman Square). The latter was a polytechnic in which the Art and Design Faculty was developing what became an influential BA in Design History that encouraged the study of and debate around designed objects of all sorts, not just those of top quality for the highest level of society. Indeed, the study of elite art and luxury was at that time rather frowned upon, and study of the silk industry not obviously a happy fit with the more democratic principles of the institution. I was fortunate, however, to have Lou Taylor as my champion and supervisor, she having proposed the project on the basis that British designers and manufacturers from the 18th century onwards always bewailed the excellence of French design over their own. Their assumptions on why this was the case needed investigation. The Research Assistant’s post that I occupied for four years required a small amount of teaching – lectures for first year fashion textile students and the supervision of a few third year dissertations. These duties punctuated periods of research in France. Never having set foot in an art school in my life, I was not best equipped to understand the needs of these students – but was fortunate to have a mentor in Lou who alerted me to the desirability of thinking about my audience and how to engage it. Courtauld-style content and presentation were not going to do the trick!

You taught the History of Design for over 20 years – how did the field change over this time?

As you say, I did teach Design History for many years, and still do, though now only through my own particular specialism (textiles, dress and museology). Indeed, I was lucky to teach not only studio-based design students, but also Design History and Humanities undergraduates, Textiles and Dress History post-graduates (I went to Winchester in 1991 to help Barbara Burman set up an MA in Textile and Dress History, which continues in a slightly different form today in Glasgow under the able stewardship of Sally Tuckett) and Textile Conservation students. When I started out, the secondary literature was very limited, so we often had to work from primary sources – and thus my awareness of object-centred study evolved. Today, there is not only a good range of reliable texts introducing the field, but multiple theoretical approaches to the subject. Earlier historical periods have gradually assumed their place in the literature (in the early days Design History was almost exclusively 19th and 20th-century in focus) and luxury production is no longer denied. The ‘material turn’ in mainstream history is also informing the field, and now, ‘Material Culture History’ provides a more inclusive term for describing what all art and design historians do, alongside archaeologists, anthropologists, and some historians, all with slightly different inflections.

You’ve produced a lot of fascinating work on the 17th and 18th centuries, with an emphasis on silk – how did your research interests develop?

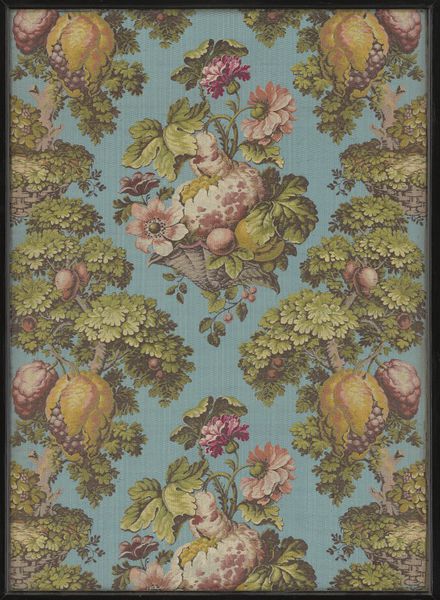

My interest in the early modern period developed through my MA special subject and dissertation, and then led directly into my PhD – and I have never let go. My initial interest in designers in the Lyon silk industry has gradually broadened into an investigation of other trades in manufacturing, notably that of manufacturer and that of salesman. Of course, my greatest pleasure is burrowing into archives to find the elusive documents I haven’t yet read – or to explore in more depth the manufacturers who emerge from my work on V&A objects. A classic example is my recent introduction to a facsimile of a merchant’s sample book of 1764, kept in the V&A collections. The identification of manufacturers’ initials in this book has given me the perfect excuse to frequent that great French gastronomic centre again – and appreciate how archive-management has evolved. Thirty years ago, I couldn’t quite believe that anyone would stick with the same subject for a life-time. Now, I understand the addiction – and, of course, now, it is much easier to travel and do research efficiently in short bursts, armed with laptop and digital camera instead of simply pencil and paper. Nonetheless, a prolonged period of time getting to know the place of production or consumption, as well as its archives, is invaluable. Silk is a very seductive fabric on which to focus, but, at the end of the day, it is the people who designed, made and wore silk that fascinate me.

You wrote a wonderful monograph on the Spanish fashion designer, Cristóbal Balenciaga. What led you to focus on Balenciaga? What do you think of the house today?

Ironically, my monograph – not wonderful, but certainly one of the first serious attempts at an analytical approach to understanding a fashion designer’s reputation through his work and context – was the result of failure. Thanks to Aileen’s recommendation, as I was finishing my PhD, Batsford commissioned me to write a book on dress in Golden Age Spain, one of a series on Dress and Civilisation. Unfortunately, the first two books in the series did not sell as well as anticipated, and since I was lagging behind (PhD dissertations never take as little time to write as one imagines), my contract was cancelled. Within a month, however, Batsford decided to launch its Fashion Designer series, asking me whether I might like to take on Balenciaga. I had French and Spanish and some knowledge of the corresponding cultures and their art, and had much appreciated the pioneering Balenciaga exhibition at the Musée des Tissus in Lyon in the first year of my PhD, which underlined the designer’s debt to textiles. Understanding of historical dress was fundamental in the case of a designer whose oeuvre owes a great debt to dress from 17th – 19th centuries. I accepted with alacrity, on the pragmatic basis that I needed to develop understanding of 20th-century fashion and textiles, if I were to teach in an art school. It is salutary to realise that in 1993, when the first edition of my book was published, there was only one other monograph on Balenciaga and little substantial on couture history. Now, one trips over such literature astoundingly frequently – and the number of student dissertations on Balenciaga is legion. As I prepare the third edition, to coincide with the V&A exhibition on Balenciaga’s Craft to open in 2017, I look forward to reflecting on the expansion in ‘Balenciaga Studies’ and to exploring with new eyes – mine and the exhibition’s curator Cassie Davies-Strodder – the expanded riches of the V&A collections. This is an exciting time for the House, as a new designer has just been appointed. Will he have the impact that Nicolas Ghesquière had in reviving its fortunes in the 1990s? Will we know by May 2017?

How have your academic studies contributed to or shaped your professional activities? What does your role at the V&A involve? What is your favourite aspect of it?

My academic studies are at the heart of all I have done and all I do in my professional life, and probably all I will do when I retire. They gave me the incentive to explore in detail objects and images in museums and documents in archives and libraries, and to be rigorous in analyzing them to formulate an argument or story. Fortunately, over the years, a great variety of different approaches to my subject have come from the tutelage of or discussion with inspiring colleagues, and I have been obliged to go through periods of being a generalist as well as a specialist, though I am a specialist by nature. My current role as Lead Curator of the Europe 1600-1815 Galleries refurbishment has been salutary in this respect, reminding me that dress and textiles do not exist in isolation, demanding that I think about them holistically and justify why I think it’s important to include them in these galleries. What I have enjoyed most about this five-year project is the teamwork collaborating with colleagues across the Museum, all with different specialisms, ideas and skills, all thinking about how we communicate with different audiences. At this stage in my career, both as Senior Curator for Textiles and Fashion at the V&A and Professor of Dress and Textiles Histories at Glasgow University, it is my pleasant responsibility to facilitate the development of the next generation of textile and dress specialists, whether through sharing subject expertise or advising on professional practice.

Could you share with us some of your goals for the future?

As you probably know, working in a museum means that institutional priorities dictate to a large extent what one’s goals are, and they can change from one year to the next. For me, a third edition of Balenciaga, this time with a focus on the V&A collections will be a short-term goal, once the Europe galleries open on 9 December. It is very exciting to imagine how beautiful this book will look in comparison with the first edition – and how much more accurate the V&A catalogue will become. I will also return to my role as one of the three specialists in the early modern period in textiles and dress, caring for the collections and ensuring both physical and intellectual access to them.

Then, of course, there are other projects that will come to fruition in the longer term, informed by my past research and executed largely in my own time: the annotated translation with my Courtauld friend, art historian Katie Scott, of a translation of the first manual of silk design published in Paris in 1765. Do look out for the small exhibition of 18th-century textiles from the Courtauld’s very own Harris collection next Spring outside the library, and the conference Fabrications that we are running on 5th March in the Research Forum. Then there is the completion of a monograph on 18th-century Lyonnais silk designer-manufacturers, and of a collaborative book project on European silks during the period of French dominance between 1660 and 1815. And, finally, in retirement, I hope to be back on the road to Spain and Portugal to continue my slightly strange academic perambulations.

Finally, do you have any advice for budding dress historians who aspire to have a career similar to yours?

Budding dress historians have to be persistent, prepared to take risks and grab opportunities, some of which may not seem terribly enticing at the time, either because of where they are or what they are. Just remember that menial and repetitive tasks often prepare you in a way that is not immediately obvious for intellectual as well as practical goals. Developing a reputation for working collaboratively and courteously is crucial.

As our subject is young and enticing to a variety of audiences, avoiding academic snobbery is a very good idea, whilst maintaining meticulous attention to detail in all you do. Aileen Ribeiro’s greatest advice to me was to learn to write at a variety of levels, in other words for different audiences – a stricture I probably didn’t appreciate at the time, but do now. I would add to that advice, that keeping on writing, even when you don’t actually have to prepare material to submit for deadlines, is important. And, of course, for ‘writing’, you could substitute ‘speaking’.

I have been lucky to have two careers, the first in teaching and the second in a national museum. I would not have been suited to the latter at the time I took up the former, so I would advocate open-mindedness as to what the future might hold. Don’t feel you have to do the same forever – even if you do want to retain your specialism, and do look beyond both museums and academia for opportunities. My main mantra may be contentious, but here it is: you can’t do dress without textiles satisfactorily, nor contemporary fashion without a background in historical styles and practices.