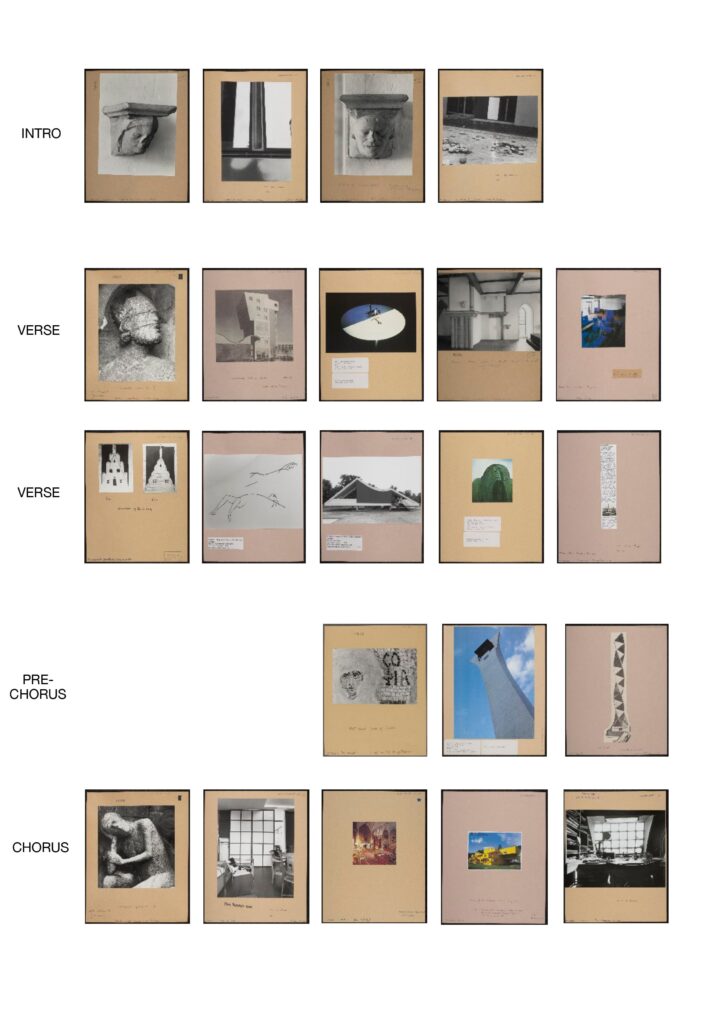

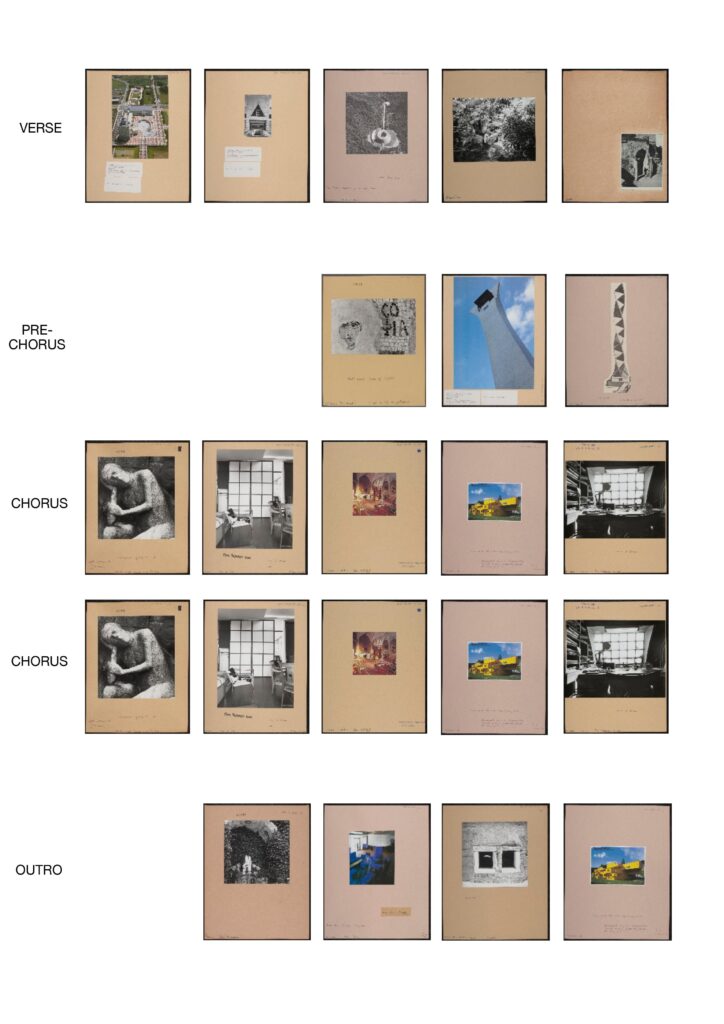

I have composed a visual song made of the images from the Conway archive. I like the idea that associations between images are what cause us to put them together – that there are certain ways that shapes interact which make us grasp them. Images have rhythms and tones, like a song. I have tried to incorporate the patterns of a song to reflect this, freely associating images from the archive – some from the same boxes – to create a whole piece which appears to randomly fit together. I have repeated some images and have tried to give the verses similar rhythms, and to give the chorus a rhythm of its own. I have tried to make these rhythms out of images.

When you are looking through the Conway archive, you are drawn to one box, then to another. They do not seem forcefully connected, but your mind draws mirrors between the images you have selected. Some of the images form a narrative, some do not. Images lead onto other images, and some appear more important than others and some do not feel worth noticing. The images feel as if they mean something together and against each other. I like the idea that making a visual song out of images is similar to the process of collecting and of taking images: it appears random but has a reason only you can fully recognise. And from this, images can become like phrases. And each phrase has a logic, just as each box in the archive has a logic which I cannot understand.

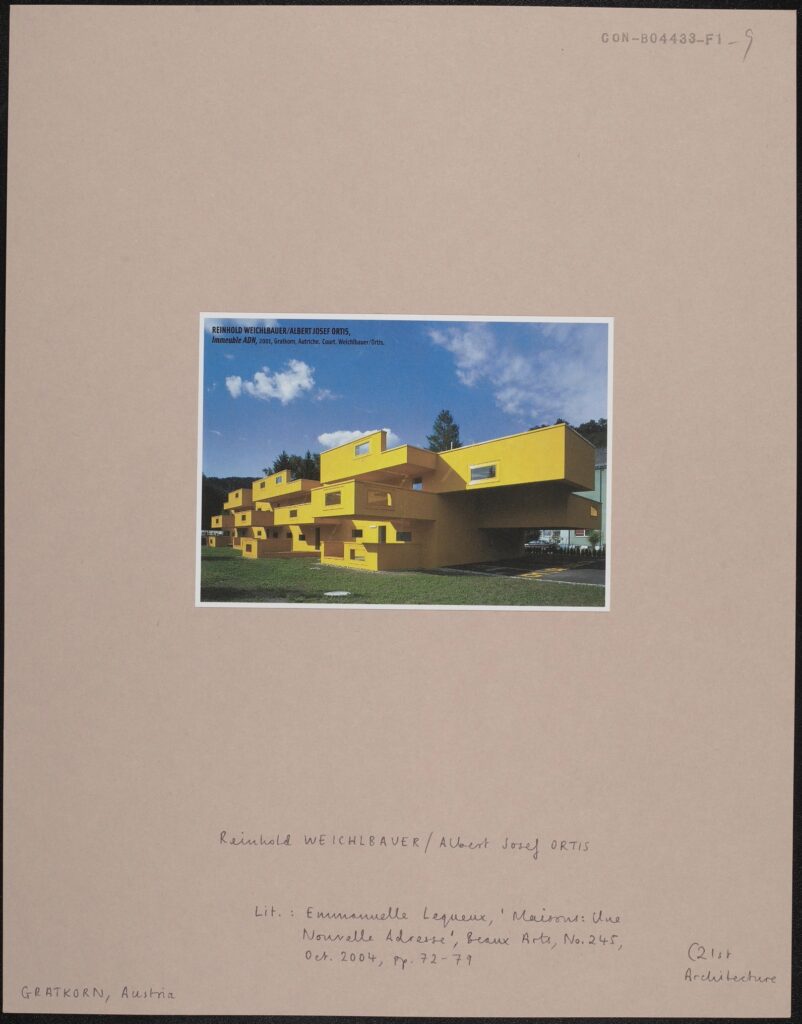

In my song, I have tried to order coloured and black and white images so that they relate to each other and create a kind of order. The intro has no colour images, until colours are slowly introduced in the verses and then repeated in the chorus. I repeated the motif of a grid in the chorus to reinforce the chorus structure. The last verse has an image which is situated at the bottom right corner of the archive page, as if finishing the progression of the verses and leading to the final choruses. The song finishes on a colour image, blue and yellow, of a small house – an image also used in the chorus. This is to mark the ending of the song and to refer to the slow progression to colour images at the beginning, which create the ending of the song.

The associations are free and tempting and indulgent – just like looking through an archive. You do not always notice the meanings or the history of images, but they show other opportunities.

Please click the link below to access a PDF file of the Visual Song.

The photographs used are listed below:

Intro

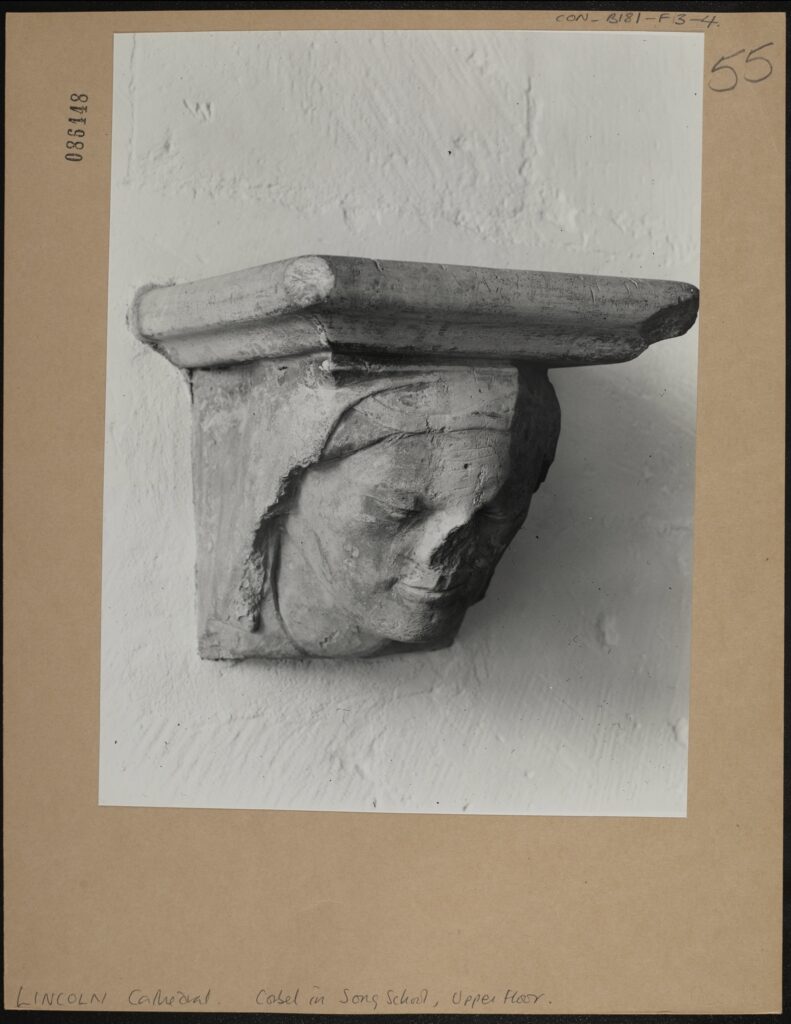

LINCOLN Cathedral. Corbel in Song School, Upper Floor. CON_B00181_F003_004, Conway Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

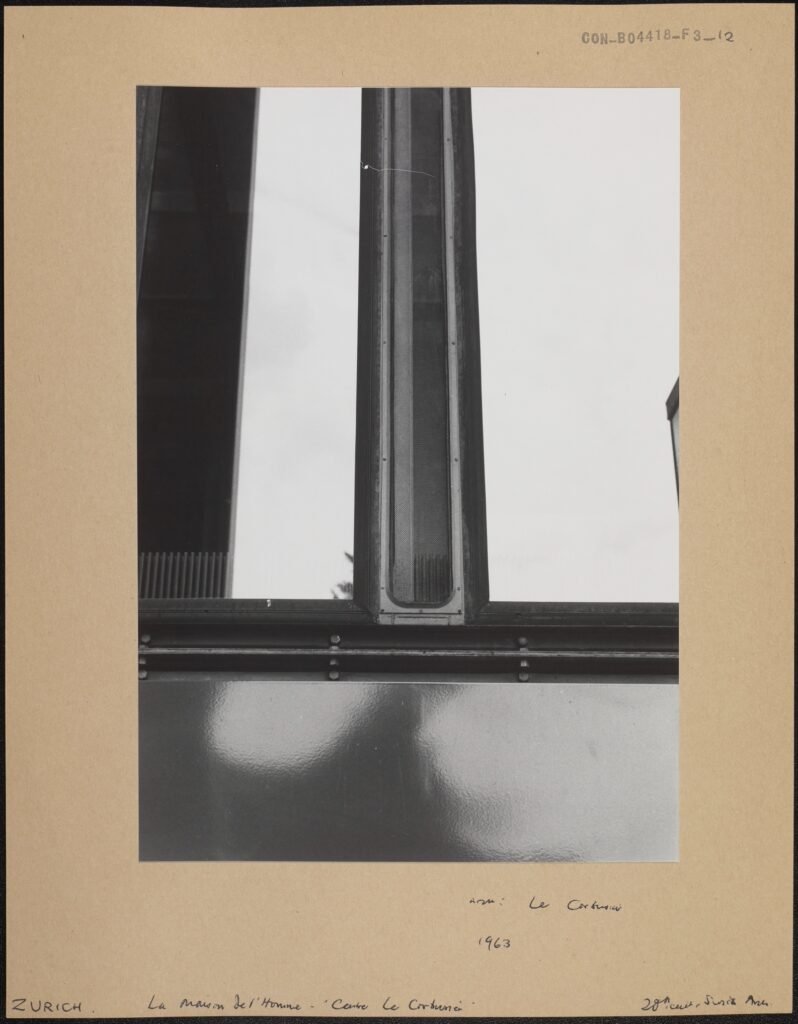

La Maison de l’Homme – ‘Centre Le Corbusier’, Architect: Le Corbusier, Zurich, 1963, CON_B04418_F003_012, Conway Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

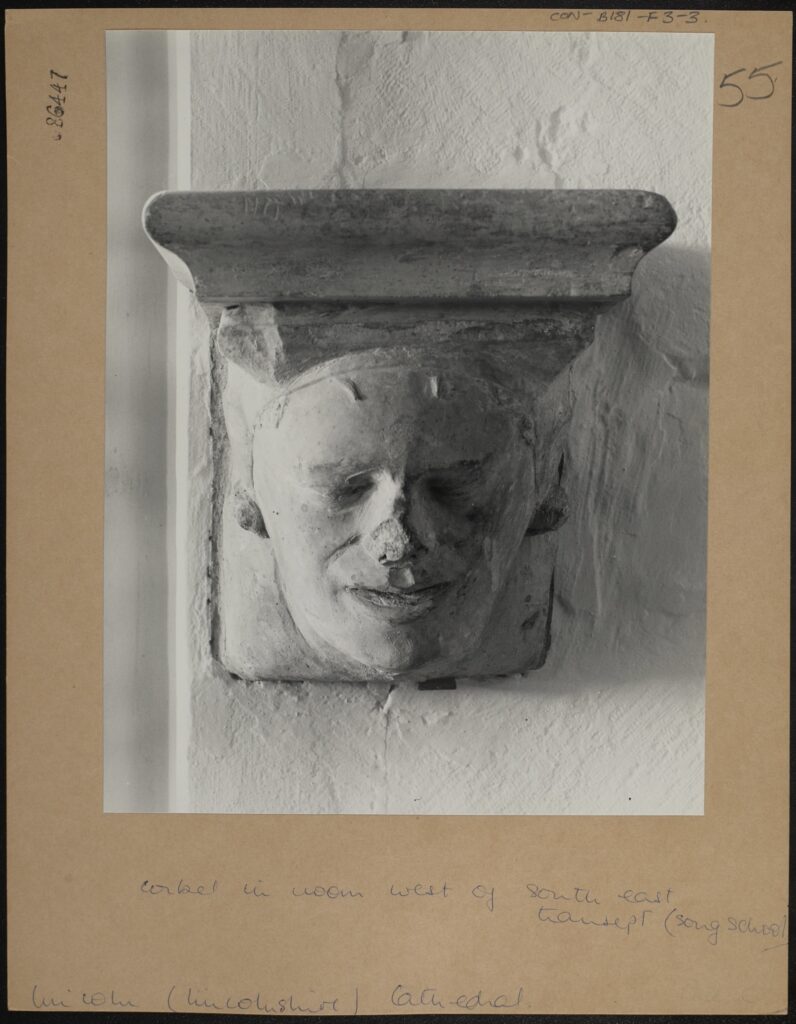

Corbel in room West of South East Transept (song school), CON_B00181_F003_003, Conway Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

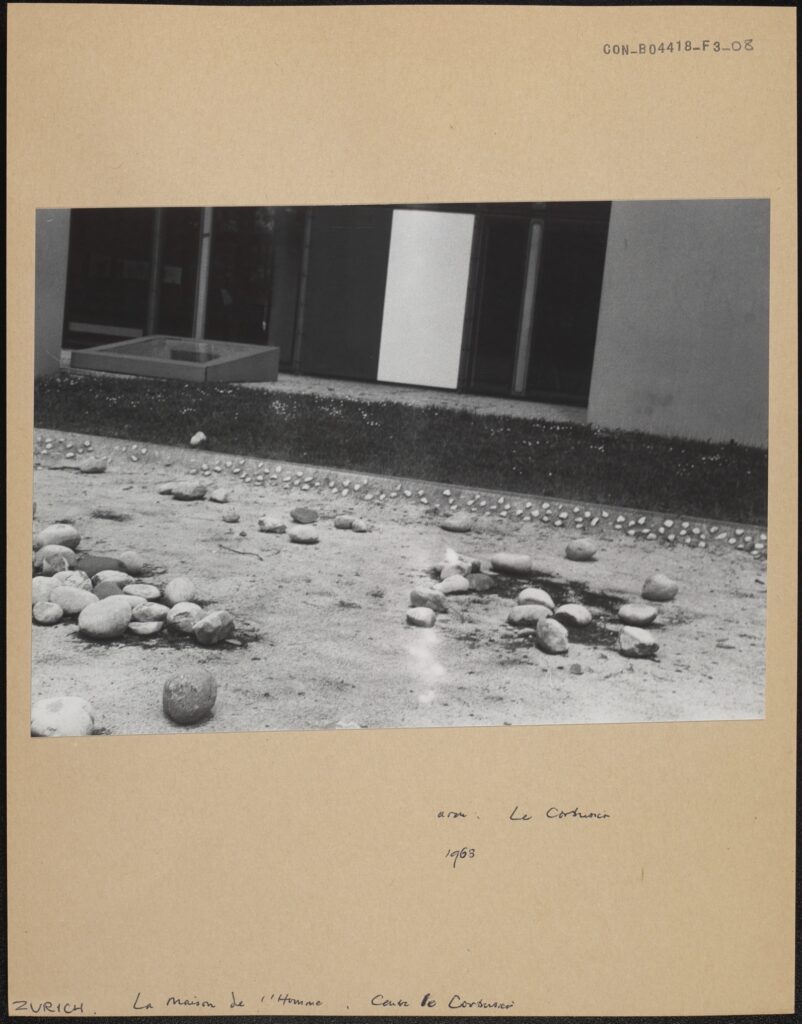

La Maison de l’Homme, le Corbusier, Centre le Corbusier, 1963, CON_B04418_F003_008, Conway Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

Verse 1

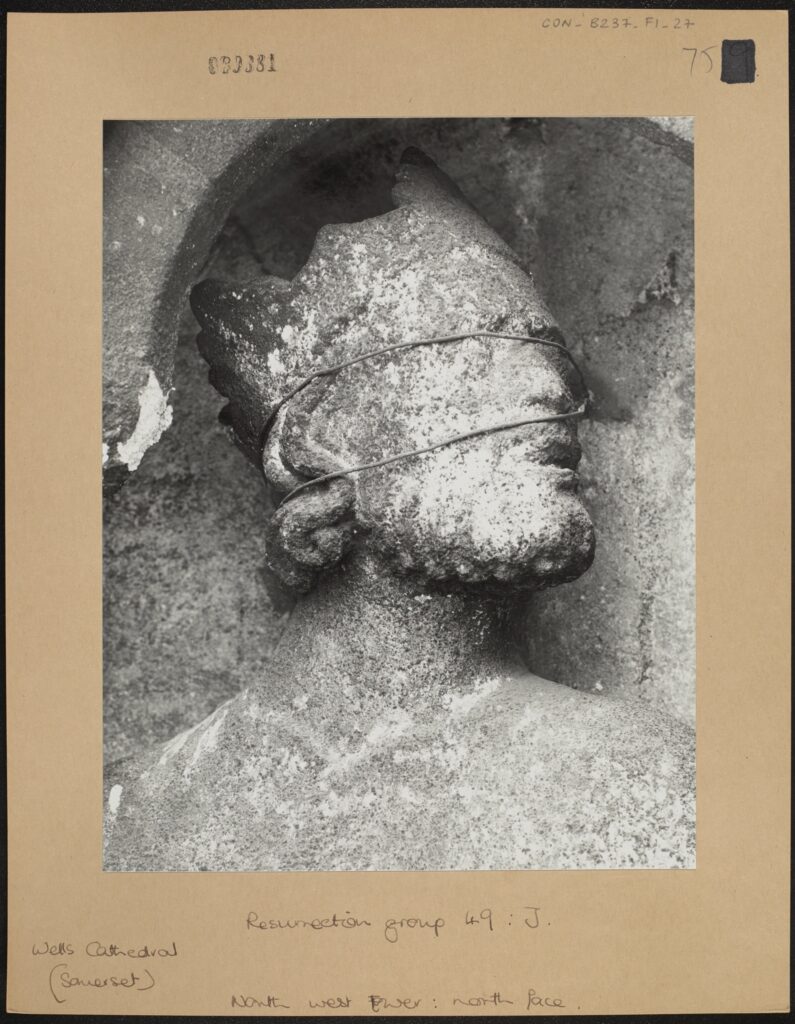

Resurrection group 49: J. North west Tower: north face. CON_B00237_F001_027, Conway Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

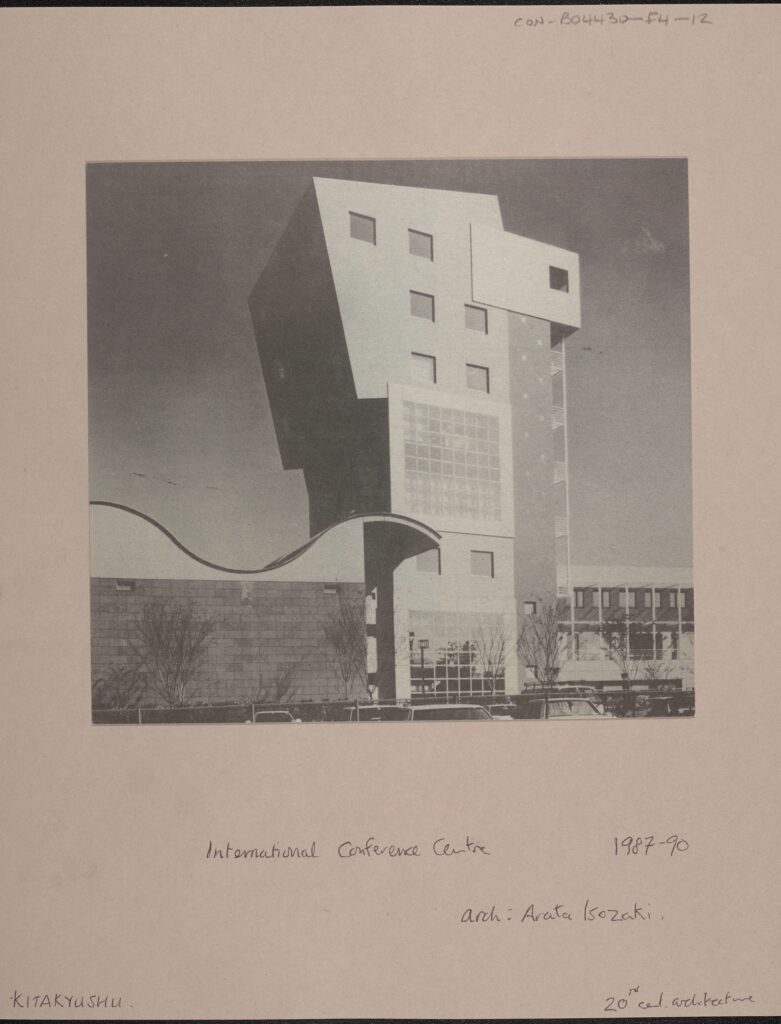

International Conference Centre, 1987-90, arch: Arata Isozaki, 20th Century Architecture, CON_B04430_F004_012, Conway Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

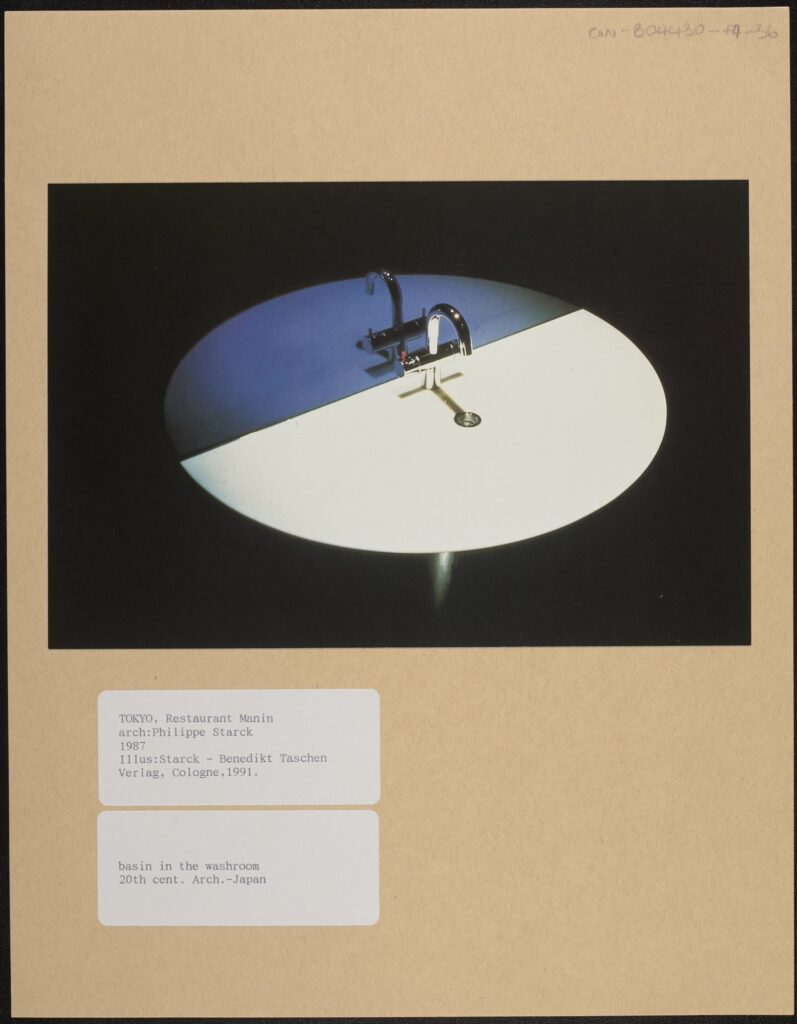

Basin in the Washroom Illustration: Starck – Benedikt Taschen, Verlag, Cologne 1991 20th Century Architecture, CON_B04430_F004_036, Conway Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

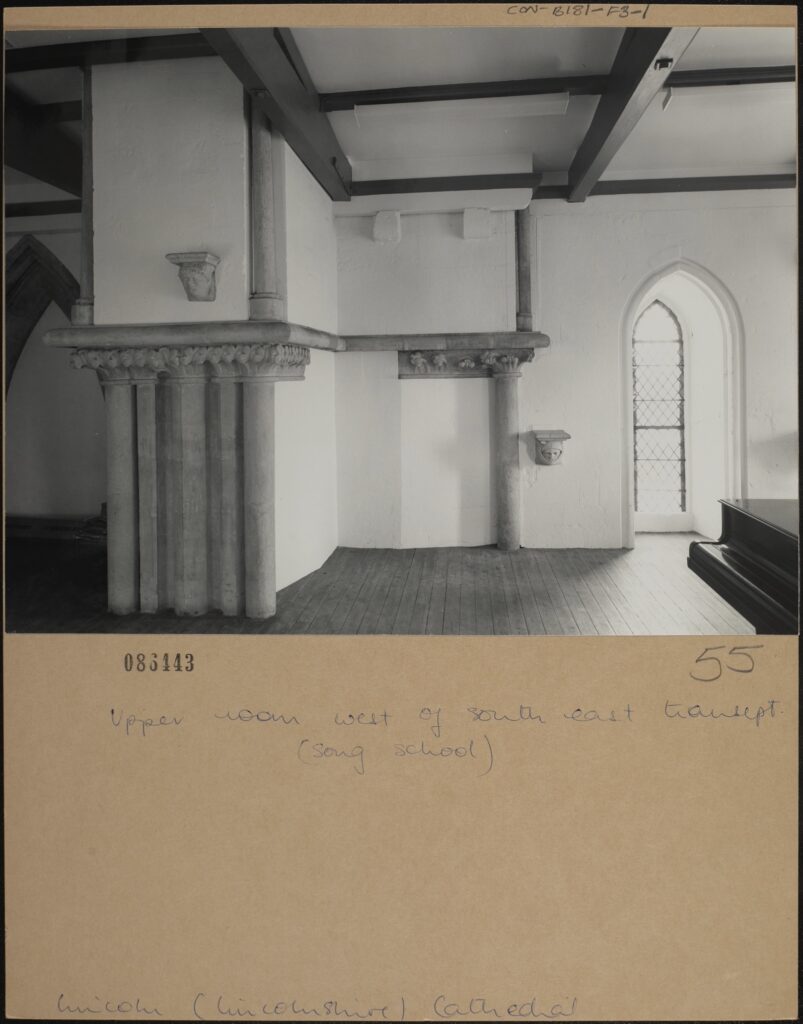

Upper room west of south east transept. (song school), Lincoln, Lincolnshire Cathedral, CON_B00181_F003_001, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

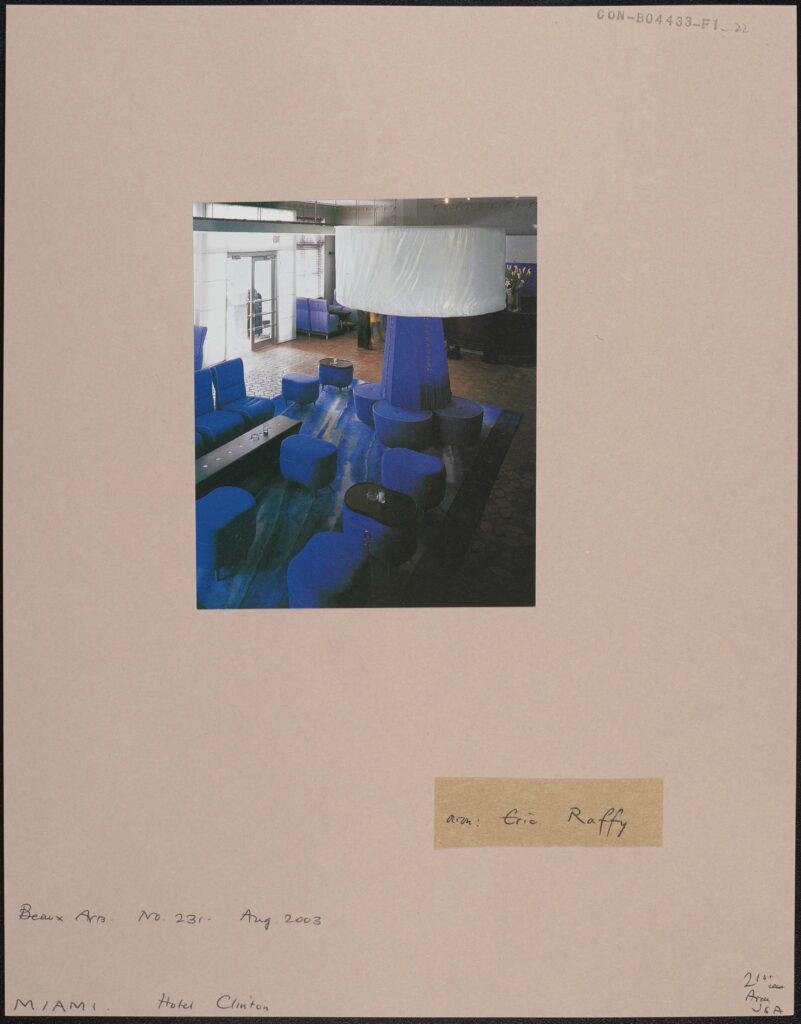

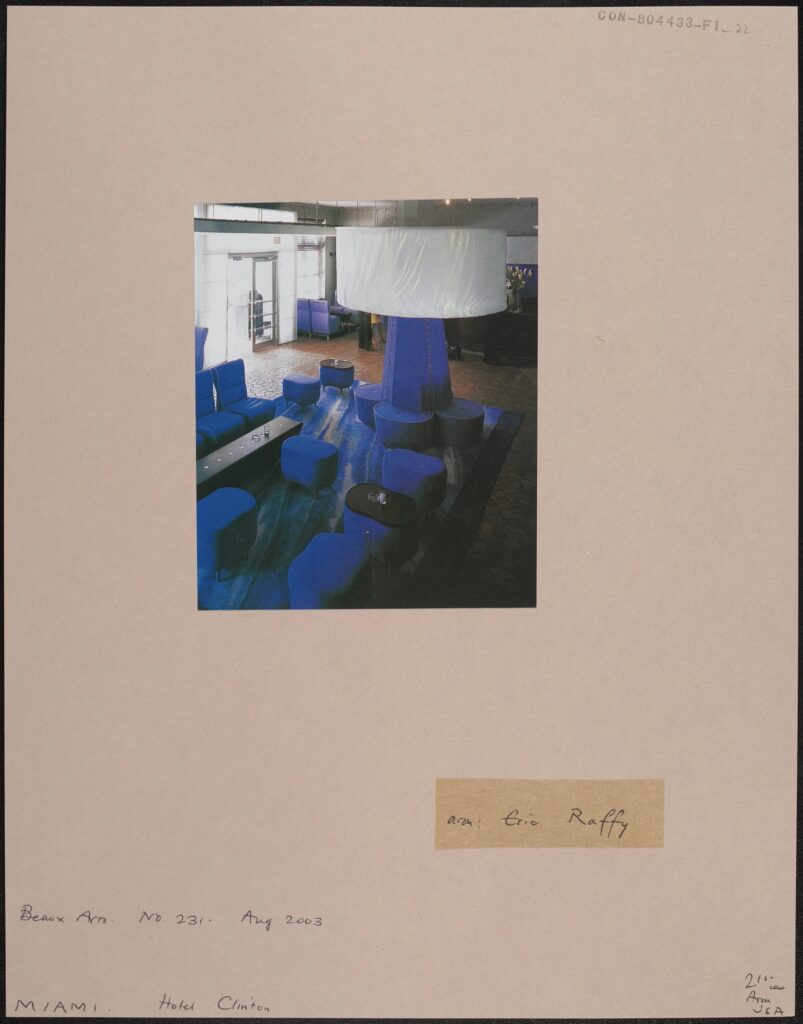

Beaux Arts No. 231, Aug. 2003, Miami, Hotel Clinton, CON_B04433_F001_022, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

Verse 2

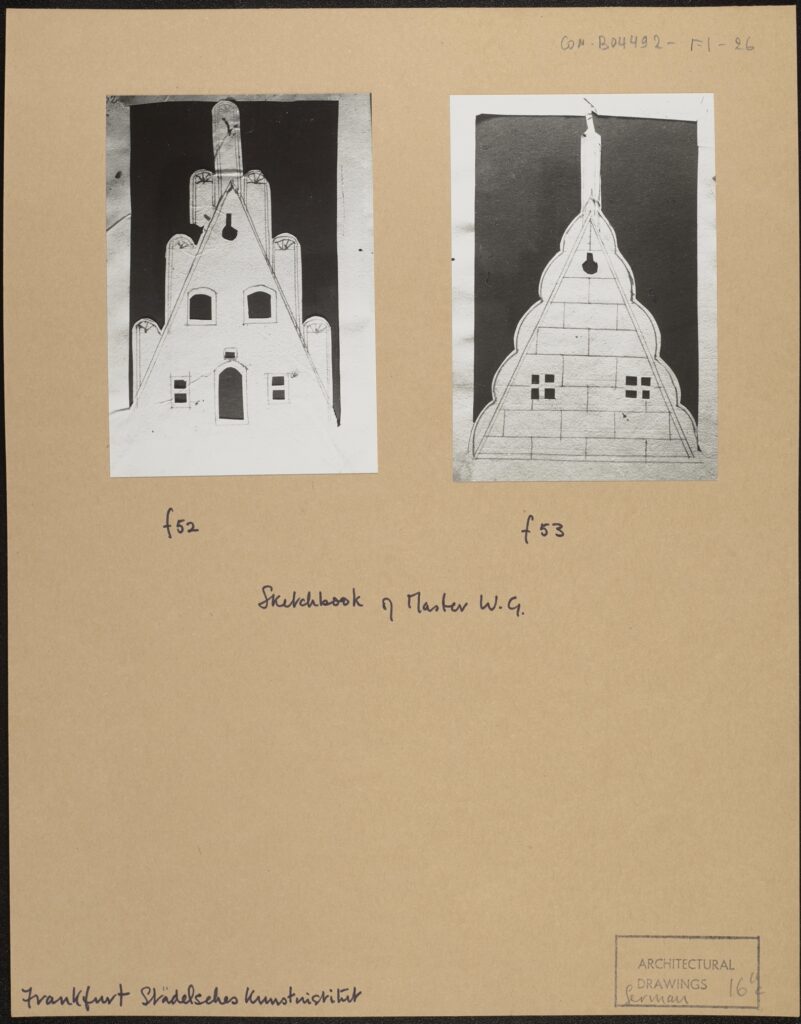

F52, f53, Sketchbook of Master W.G., Frankfurt Stadelsches Kunstinstitut, CON_B04492_F001_026, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

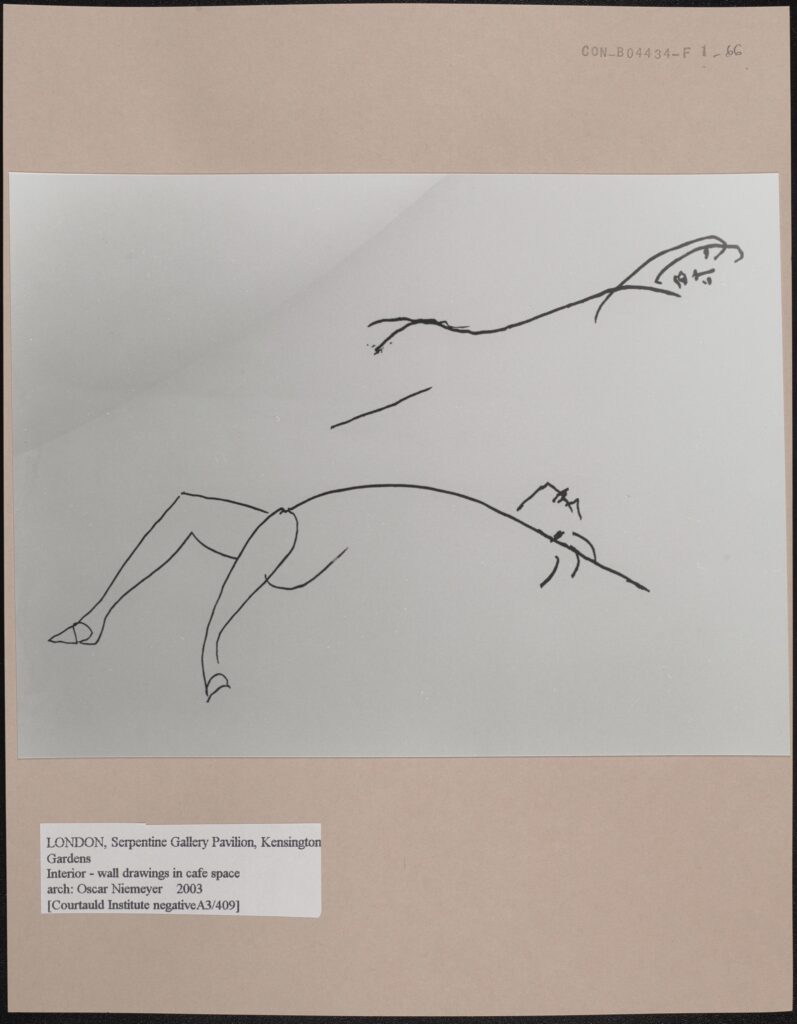

Interior – wall drawings in cafe space, London, Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, Architect: Oscar Niemeyer, 2003, CON_B04434_F001_066, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

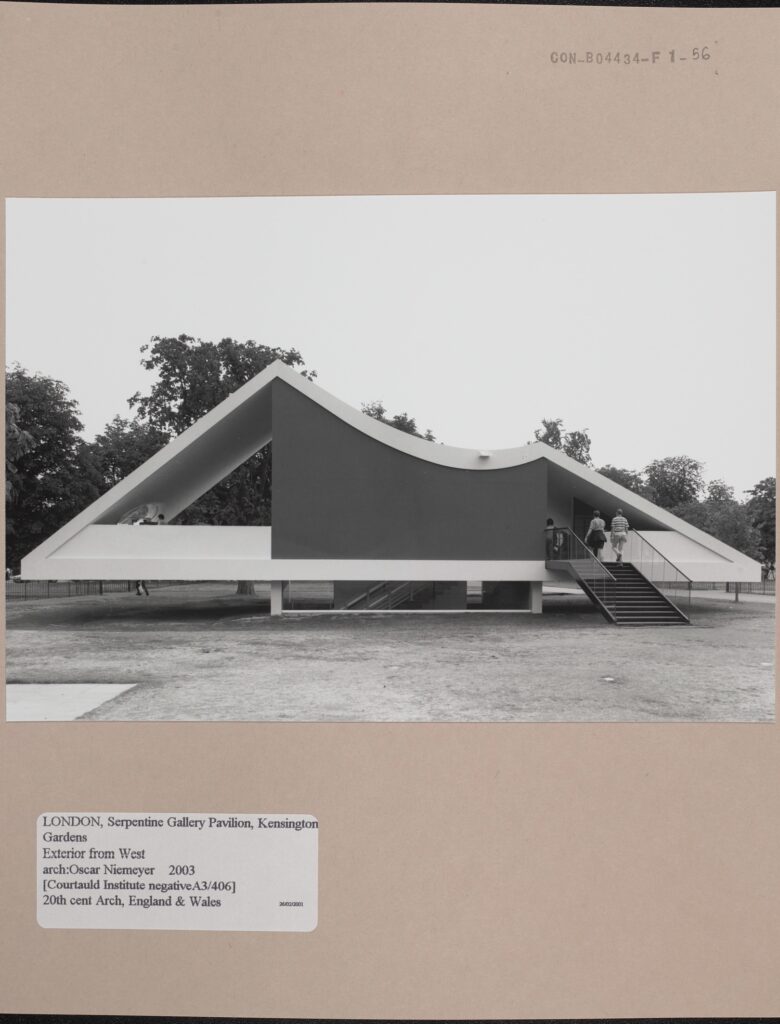

Exterior from west (Courtauld Institute Negative A3/406) 20th century Architecture, England and Wales, London Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, CON_B04434_F001_056, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

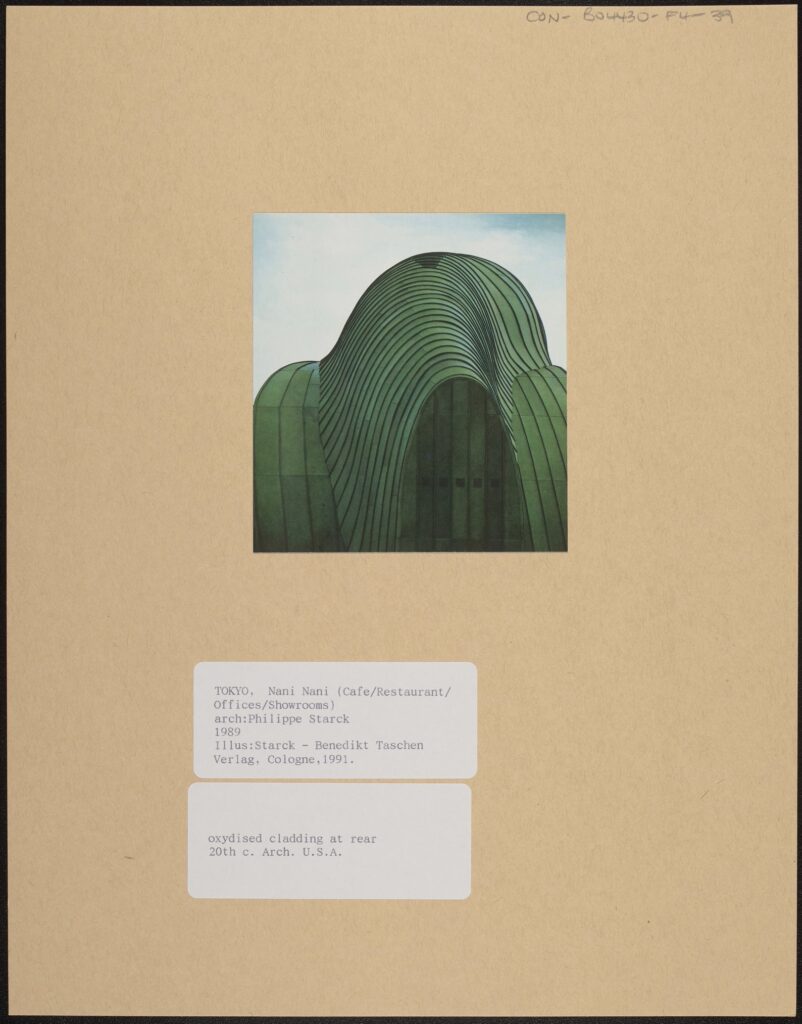

Oxydized cladding at rear. Illus: Starck -Benedikt Taschen Verlag, Cologne 1991, CON_B04430_F004_039, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

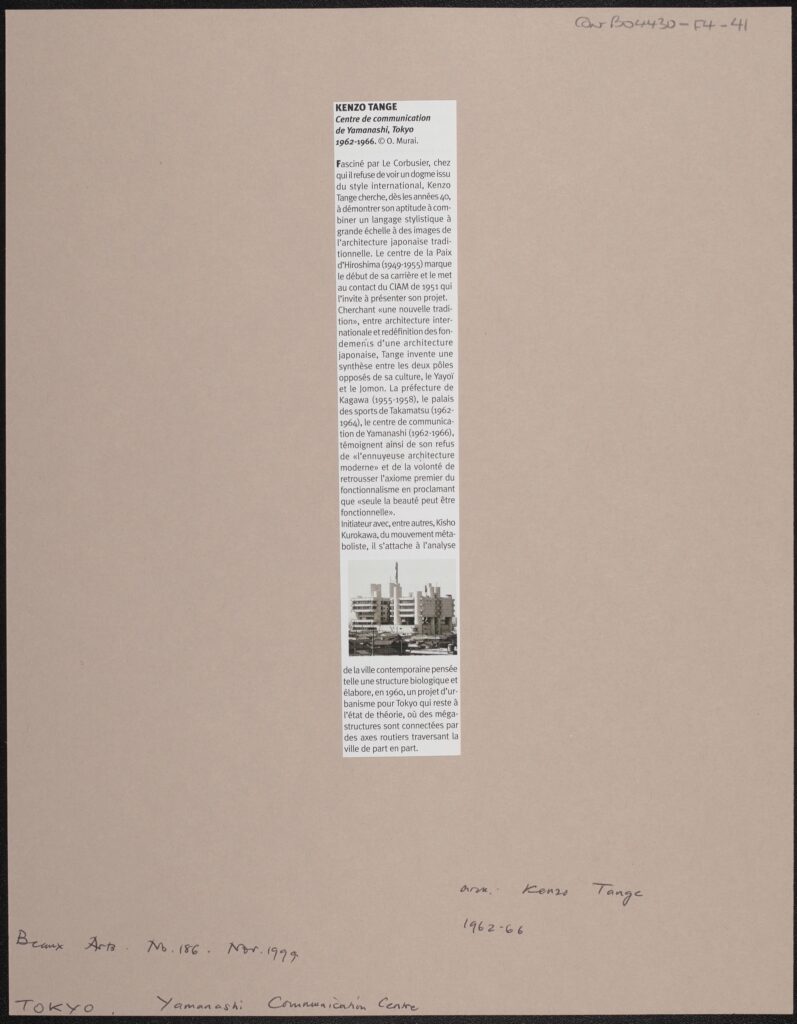

Beaux Arts No. 186, November 1999, Yamanashi Communication Centre, CON_B04430_F004_041, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

Pre-Chorus

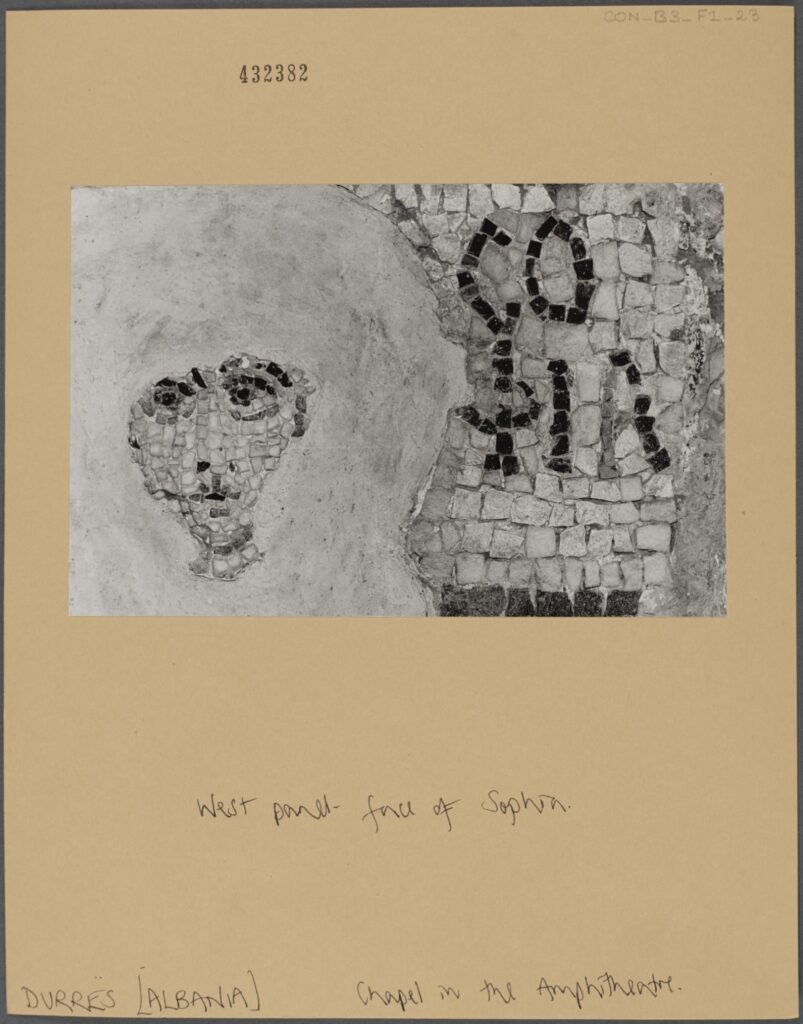

West panel – face of Sophia. Chapel in the Amphitheatre, Durres, Albania, CON_B00003_F001_023, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

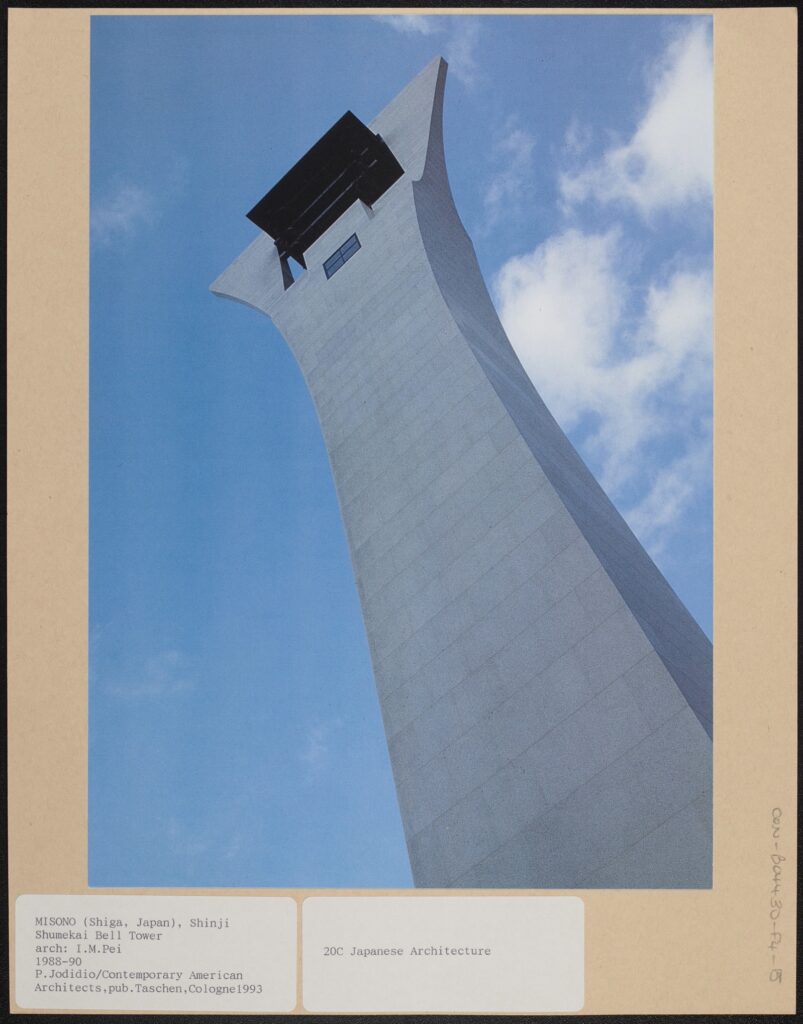

P. Jodidio/Contemporary American Architects, published Taschen, Cologne, 1993: 20th century Japanese Architecture. CON_B04430_F004_015, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

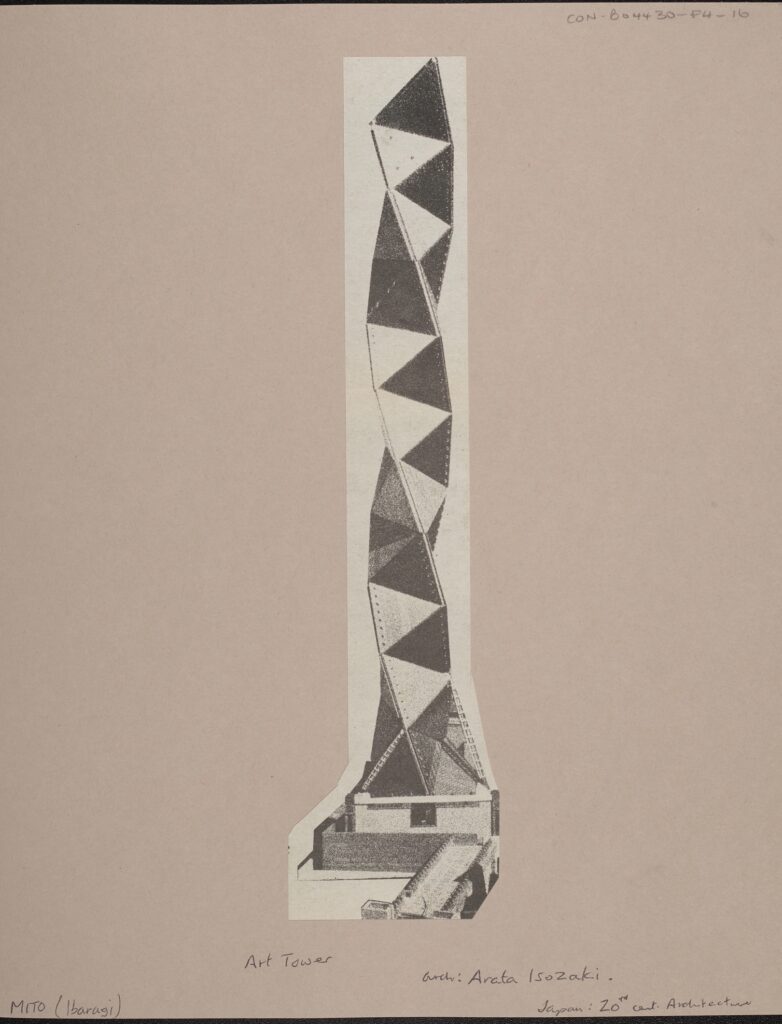

Art Tower, arch: Arata Isozaki, Japan: 20th Century Architecture, CON_B04430_F004_016, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

Chorus

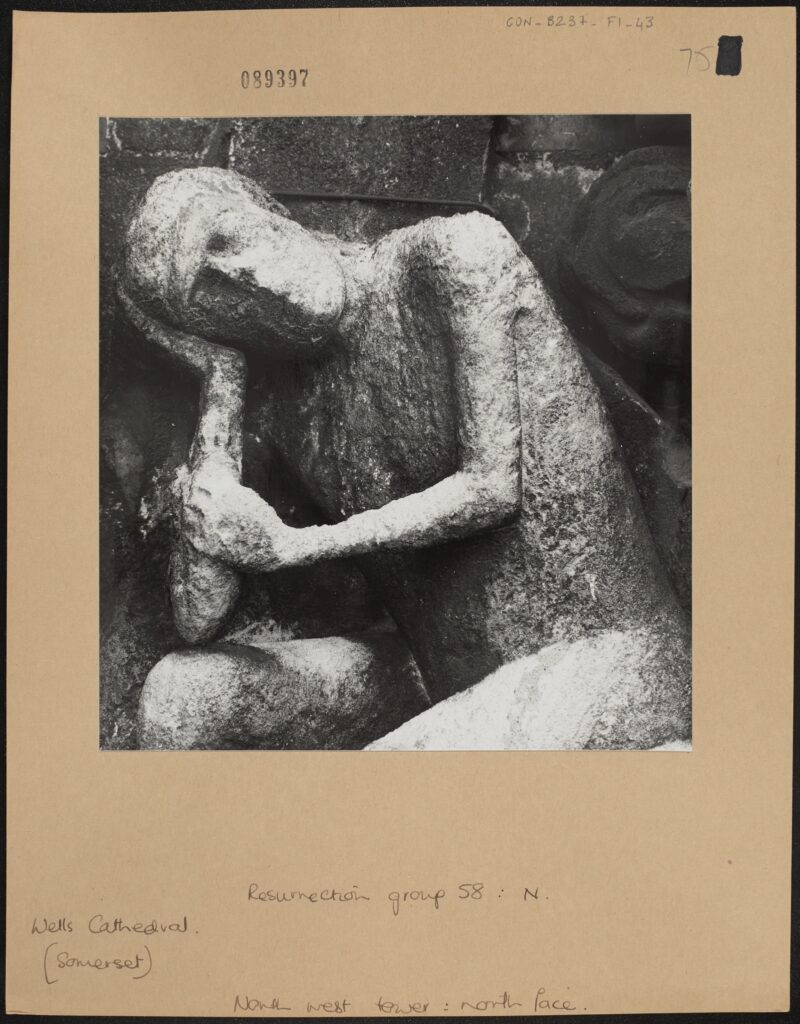

North west tower: north face. Resurrection group 58: N., Wells Cathedral, Somerset, CON_B00237_F001_043, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

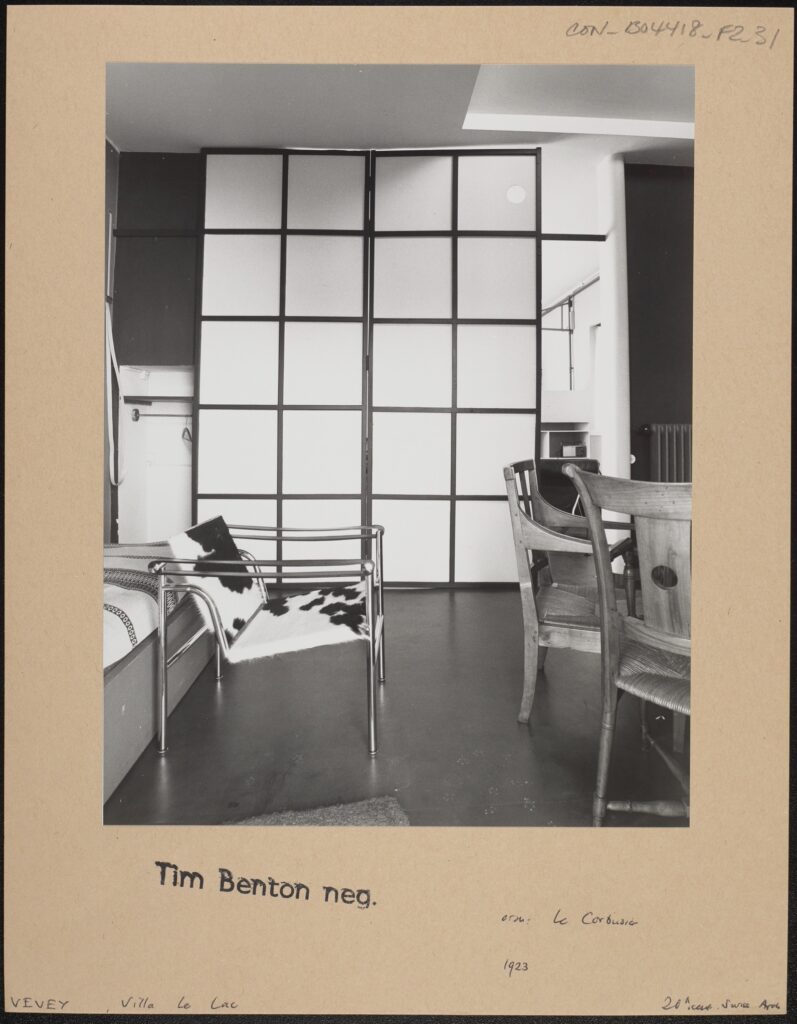

Tim Benton negative 20th Century Architecture, Vevey, Villa le Lac, CON_B04418_F002_031, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

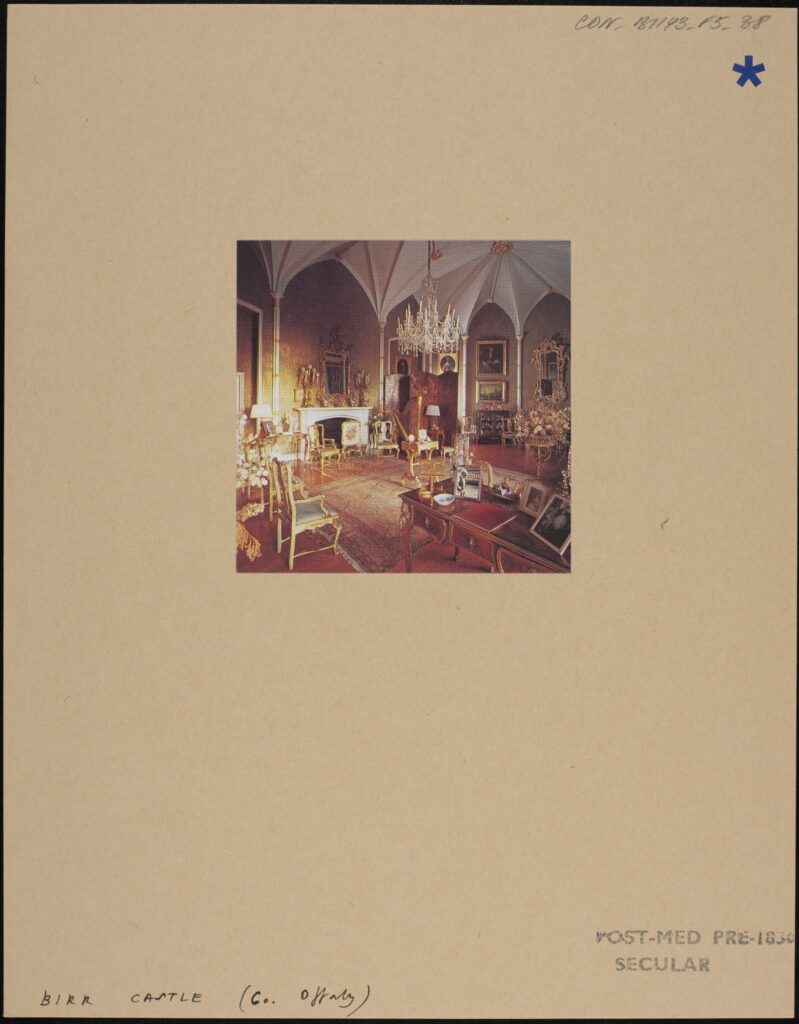

Birr Castle [colour interior: sitting room], CON_B01143_F005_038, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

Literature: Emanuelle Lequeux, ‘Maisons: Une Nouvelle Adresse’, Beaux Arts, No.245, October 2004, pages 72-79. 21st century Architecture. CON_B04433_F001_009, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

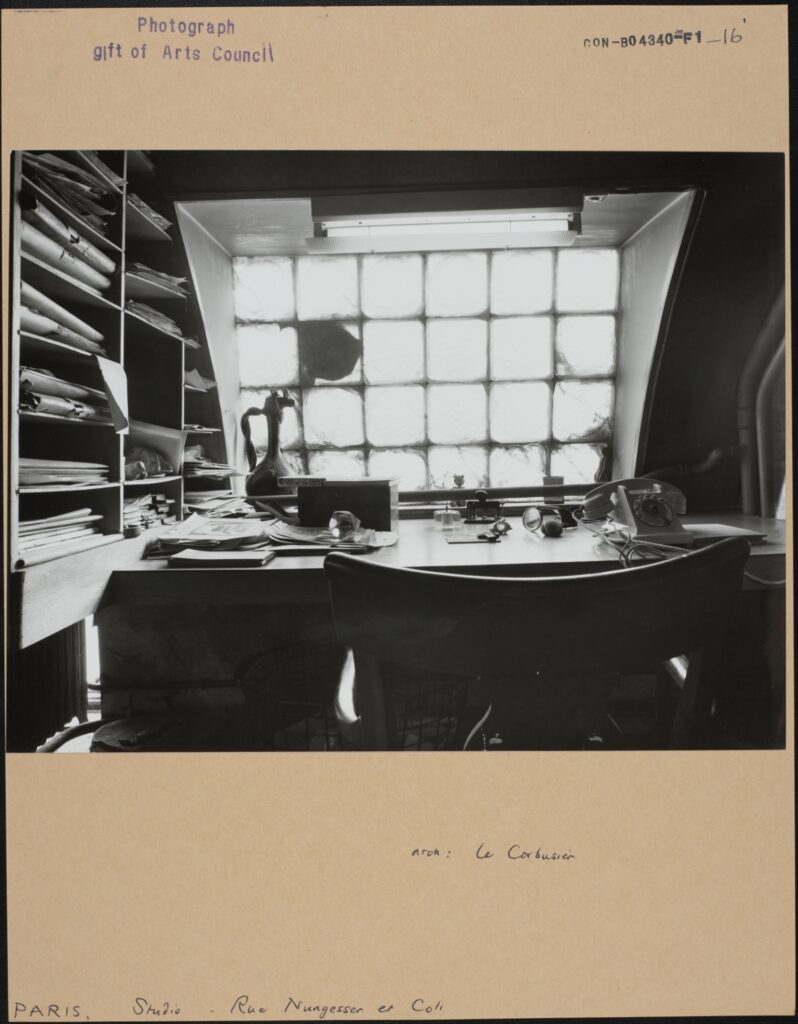

Le Corbusier, Paris, Studio Nungesser et Coli, CON_B04340_F001_016, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

Verse 3

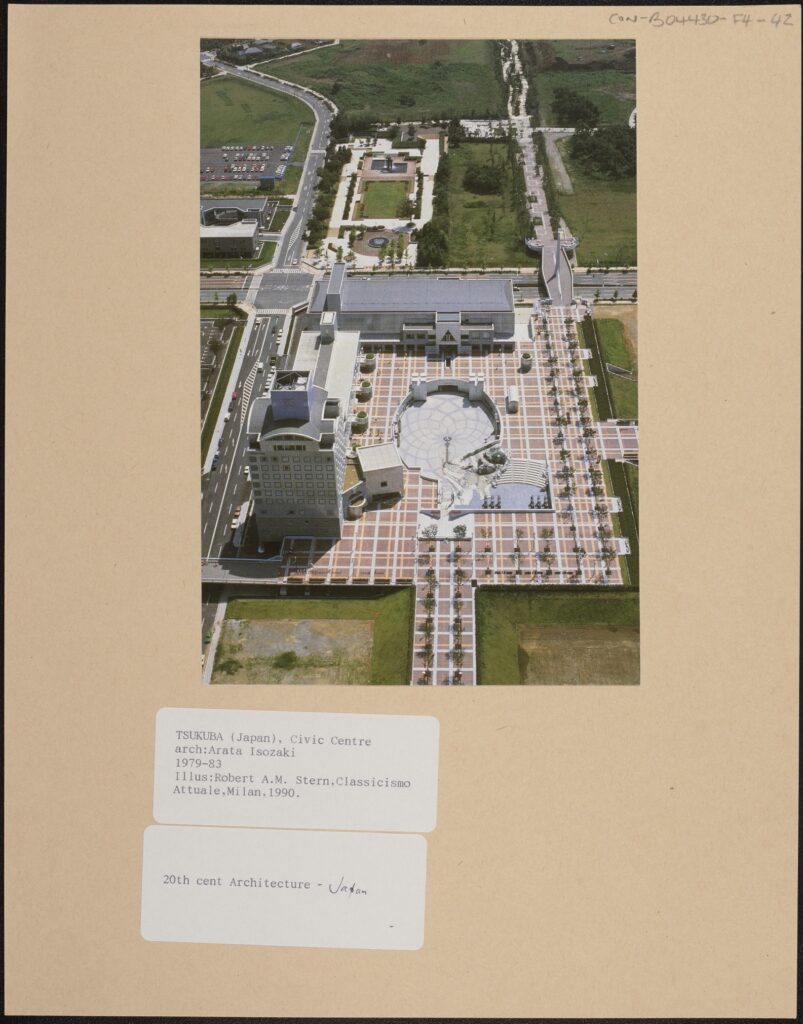

Overhead view of plaza and buildings Illustration: Robert A.M. Stern, Classicismo Attuale, Milan, 1990. 20th Century Architecture – Japan, CON_B04430_F004_042, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

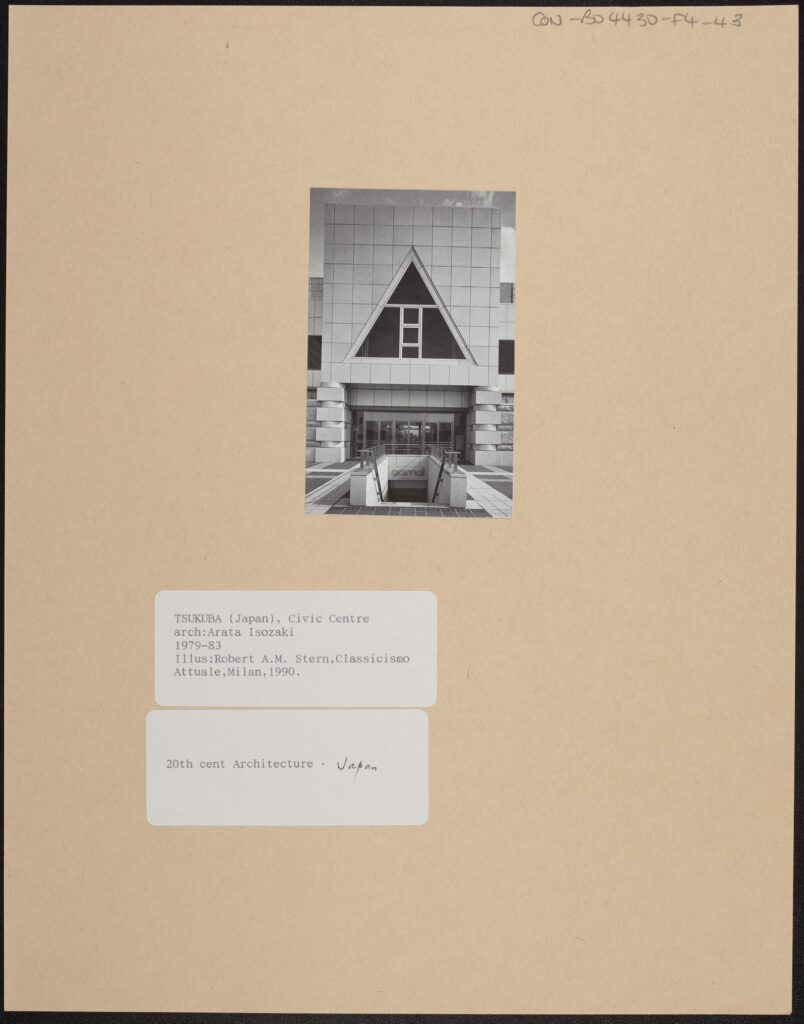

Tsukuba, Civic Centre, arch: Arata Isozaki, 1979-83, Illustration: Robert A.M. Stern, Classicismo Attuale, Milan, 1990, CON_B04430_F004_043, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

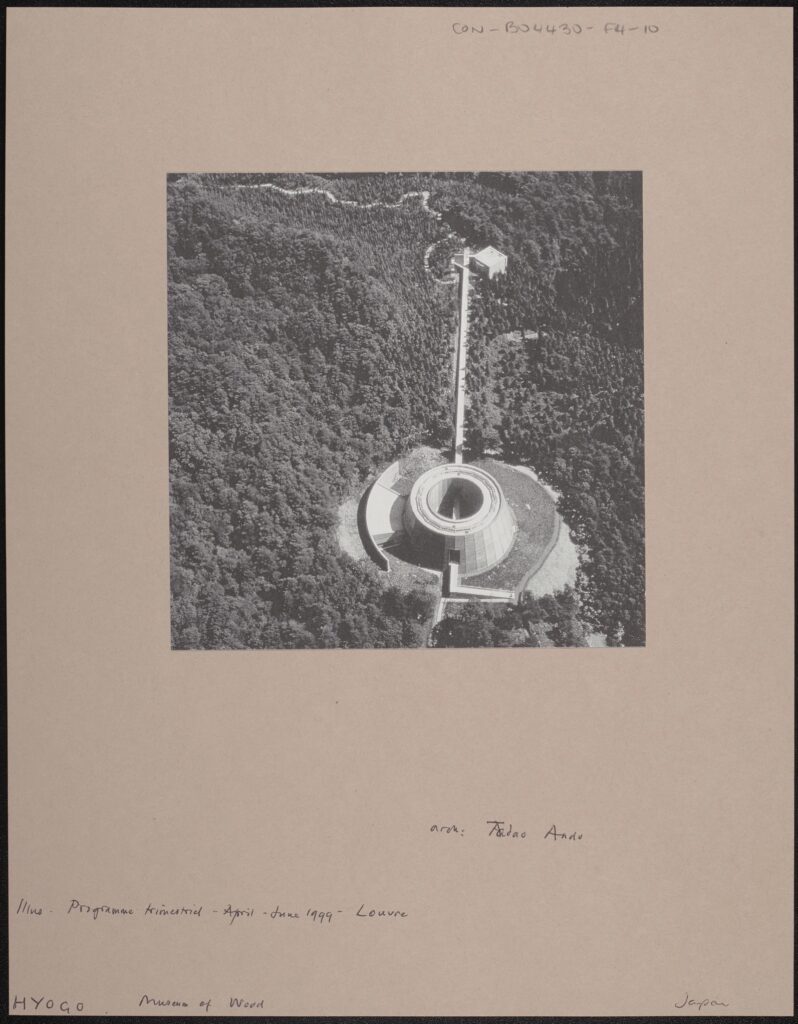

Illus. Programme trimestriel – April – June 1999 – Louvre, Hyogo, Museum of Wood, CON_B04430_F004_010, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

Alexandria, CON_B01218_F002_002, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

Roman Basilica, Luxor, CON_B01218_F009_002, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

Outro

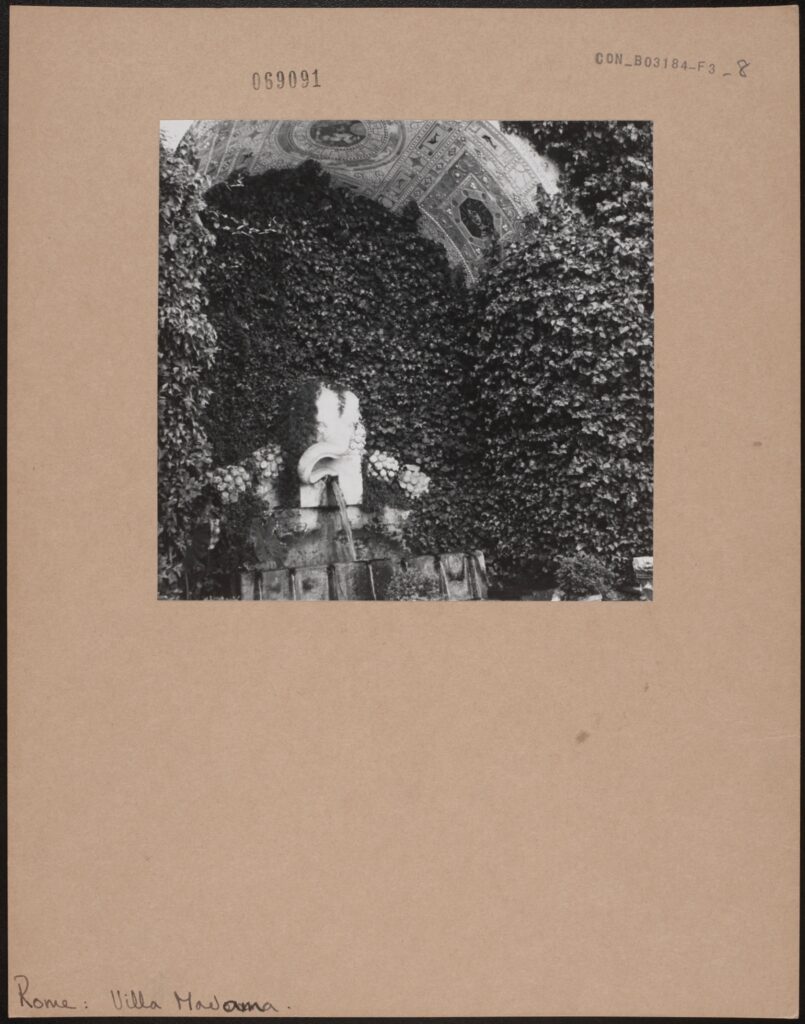

Rome, Villa Madama: Exterior: Gardens, CON_B03184_F003_008, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

Hotel Clinton, Miami, Beaux Arts No. 231, Aug. 2003., CON_B04433_F001_022, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

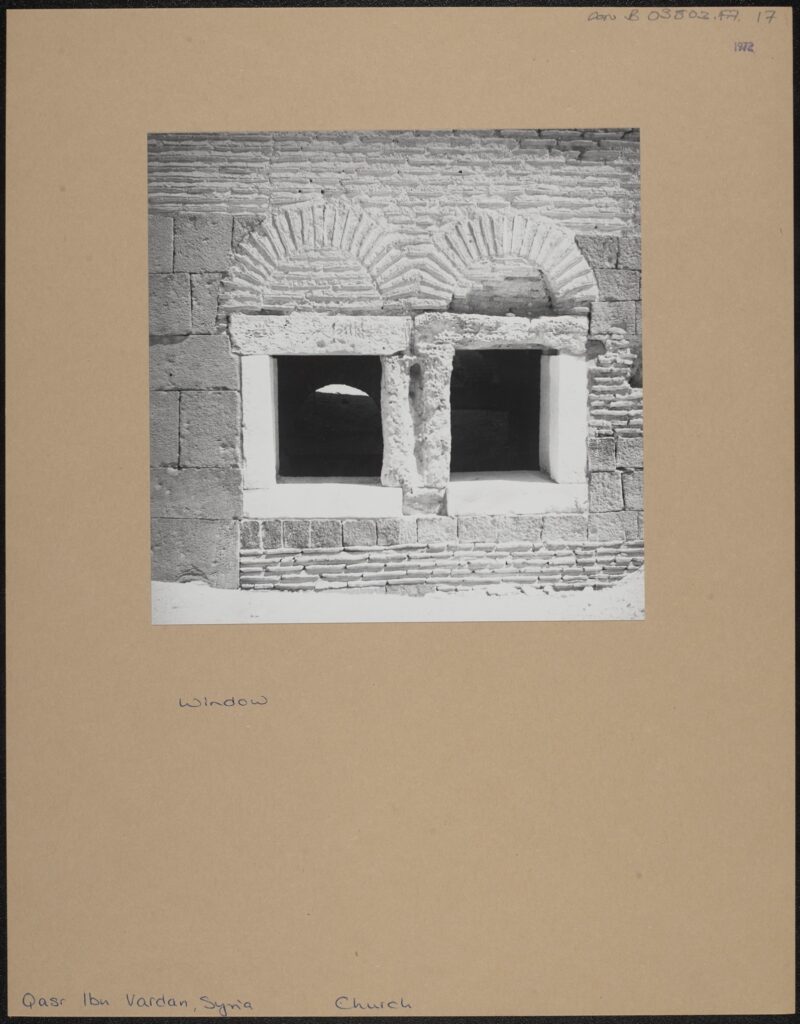

Window, taken in 1972, Qasr Ibn Vardan, Syria, Church, CON_B03803_F007_017, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

Literature: Emanuelle Lequeux, ‘Maisons: Une Nouvelle Adresse’, Beaux Arts, No.245, October 2004, pages 72-79. 21st century Architecture., Gratkorn, Austria, CON_B04433_F001_009, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

Iris Campbell-Lange

Courtauld Connects Digitisation

Oxford University

Micro-Internship Participant