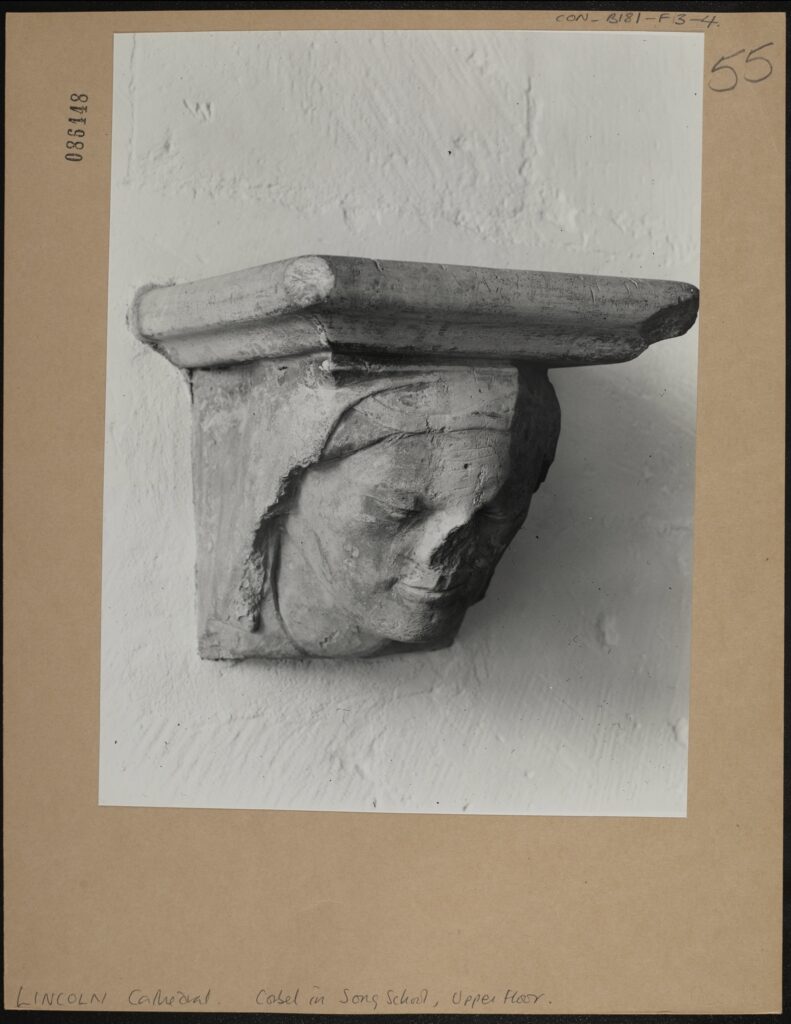

Box CON_B09765 is full of destruction. Perusing the photographs within, you encounter crumbling palaces, streets full of rubble, and churches that have become unrecognizable. This box contains part of the Macmillan Commission’s archive of formerly confidential photographs showing second world war bomb damage in Austria, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Each mounted photograph has a notice on the back that reads:

RESTRICTED.

The information given in this document is not to be communicated either directly or indirectly, to the Press or to any person not authorised to receive it.

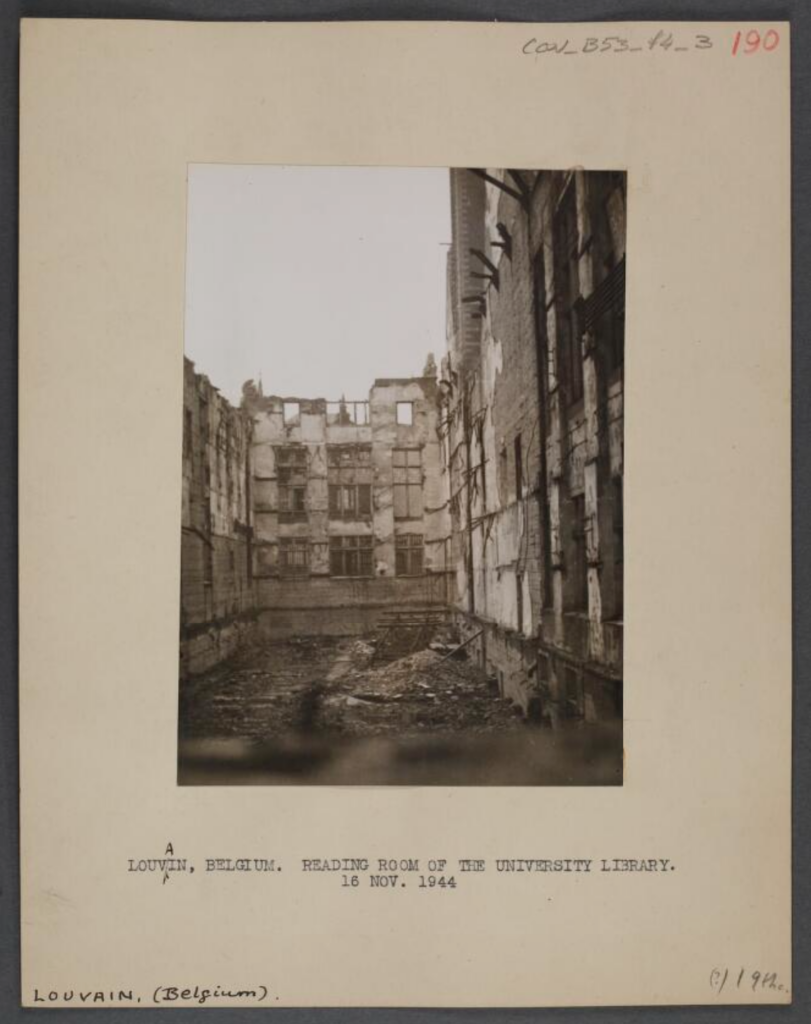

This message, along with the fact that this box remains undigitised*, contributes to a sense of reverence one must feel for the photographs. It is privilege to help steward these images, which have been obscured from the public’s view for nearly eighty years, into public memory. The damage that the photographs show is nearly incomprehensible. Yet, inside this box one image stands out as a testament to hope.

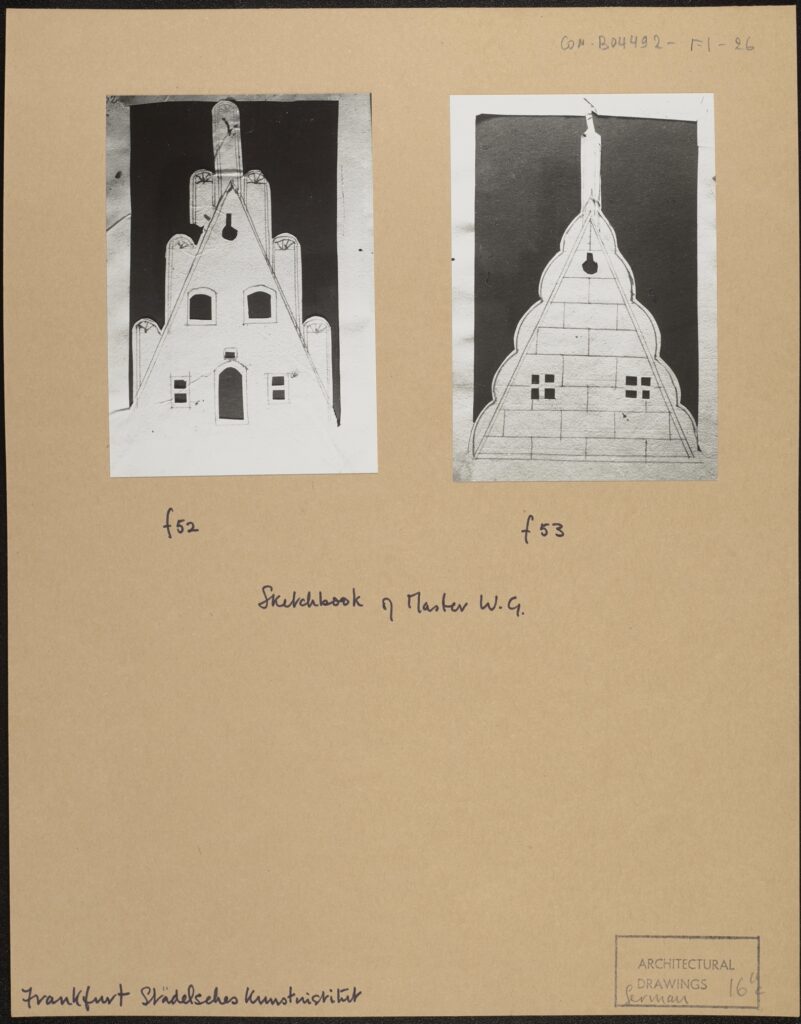

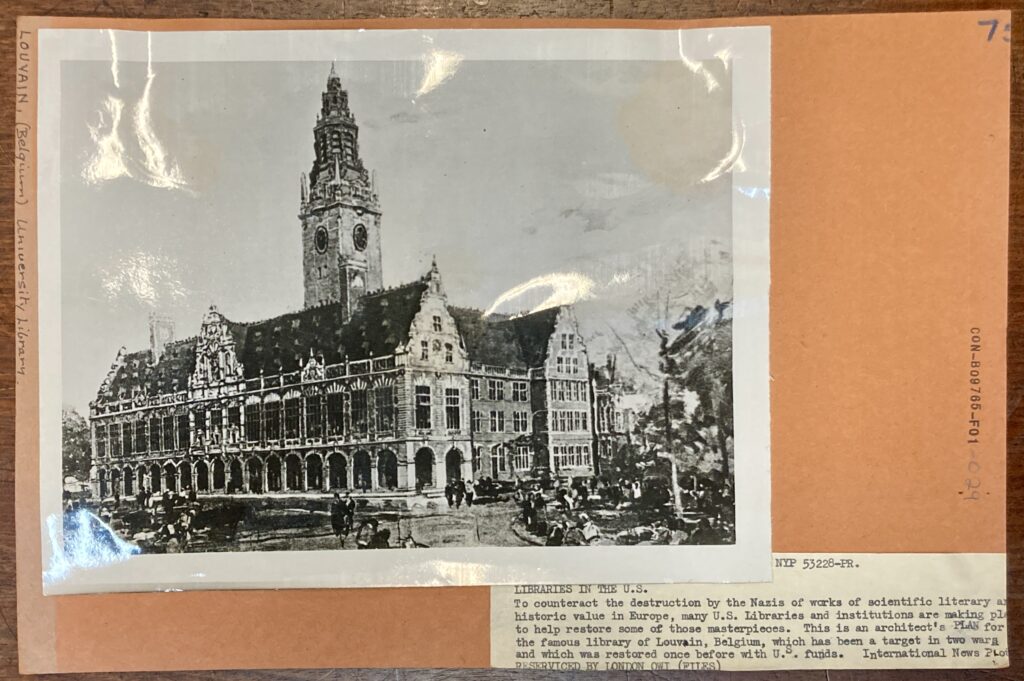

CON_B09765_F001_029 is one of few images of intact buildings in this box, but its slight haziness differentiates it from the others. While the crisp uniforms of American G.I.s are in sharp focus in other photos in the Macmillan archive, the people milling about the foreground of this image are little more than smudges. You can tell that the structure in the image, which has three gables and a spire, is meant to be magnificently detailed, but the rows of what seem to be windows that dot the roof appear more like shadows. The photograph invites speculation in a box that is firmly rooted in a historical reality.

The caption reveals why this photograph, which is differentiated by its style and mood, is included in box CON_B09765:

Libraries in the U.S.

To counteract the destruction by the Nazis of works of scientific literary an

historic value in Europe, many U.S. Libraries and institutions are making pla

to help restore some of those masterpieces. This is an architect’s PLAN for

the famous library of Louvain, Belgium, which has been a target in two wars

and which was restored once before with U.S. funds. International News PLo

RESERVICED BY LONDON OWI (FILES)

Among the Macmillan archive, there are many photos of soldiers recovering artefacts from historical churches and architects assessing the damage in preparation for restoration, but this was the only image I could find in the Macmillan archive that showed that libraries were a priority for post-war repair.

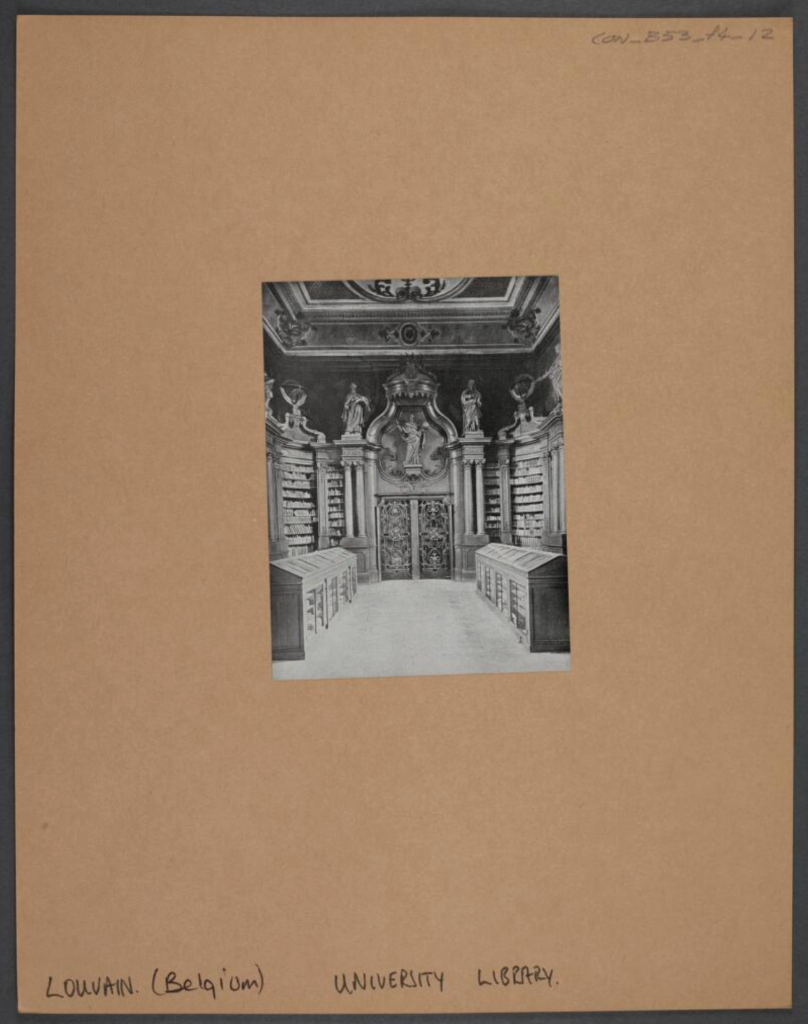

Looking further into the history of the library of the Université catholique de Louvain reveals that it was victim to both the first and second world wars. In 1914, the library was burnt down by the German army, destroying most its collection of manuscripts and rare books and modern printed works. The destruction and rebuilding of the library was a significant moment in the British and American cultural imagination. The John Rylands Library in Manchester solicited donation of books from libraries across the UK and its former colonies. President Herbert Hoover, then U.S. Secretary of Commerce, was a champion of the project to rebuild the library. Money to support the restoration project was crowdfunded from American institutions and private citizens via the National Committee of the United States for the Restoration of the University of Louvain, as well as through German reparations as per the terms of the Treaty of Versailles.

American architect Whitney Warren designed the reconstruction, which started in 1921. He courted controversy, planning to inscribe the building with the Latin phrase: “Furore Teutonico Diruta, Dono Americano Restituta”, which translates to “Destroyed by German fury, rebuilt by American donations”. The plan for inscription was eventually scrapped, as it was seen as an unnecessary admonishment of post-war Germany, and the building was completed in 1928.

CON_B09765_F001_029, the image of the plan for the library’s reconstruction in the Conway library, however, is dated from the second time the library was destroyed, according to the caption provided by the Macmillan archive. The library burned down again, probably caused by an exchange of artillery fire between Nazi and British forces, and most of its restored collection was lost.

Curiously, secondary source histories of the library focus primarily on the first destruction and rebuilding process and provide relatively few details about the second, which took place from 1944–51.

It seems that the second restoration did not capture the public’s attention to nearly the same degree. A search of the British Library’s newspaper collection for articles about the second destruction of the Louvain library returns only reporting about the second destruction of the library and not its reconstruction. Admittedly, this archive ends in 1950 before the library was reopened. The Macmillan archive photos were not available to the British press, which could be a contributing factor to this. The same search in the Library of Congress’ Chronicling America archive, which extends beyond that date, provides more context about the second reconstruction but also focuses primarily on the destruction of the library.

Most American newspaper articles reporting on the destruction of the library in 1940 harken back to the role that prominent Americans, as well as the American populace, played in the original restoration. One opinion printed in the Washington Evening Star even abdicates the United States from the responsibility of restoring the library once more, and instead assigns that task to the Nazis: “The lovely Library of Louvain, rebuilt after the last war by contributions from American school children, has been destroyed again. Most of us can think of a group of highly skilled workmen to whom well might be assigned the postwar task of a second reconstruction. Terms of the arrangement would be long hours, good grub and no pay”.

In these two databases of English-language newspapers, as well as in the archives of the New York Times and the Washington Post, I wasn’t able to find conclusive information about who was responsible for financing the rebuilding of the Louvain library the second time. (Without speaking French or Flemish, I couldn’t look for additional information in contemporary Belgian newspapers.) Based on speculation from the New York Herald Tribune, it seems that the task fell to the Belgian government and the university itself.

Americans remained involved in helping to restore the library’s collections, though, as did the international community. The Louvain Book Fund was an American charity, again supported by President Herbert Hoover and others, that fundraised for the purchasing of a new collection. The Library of Congress and the American Library Association, along with other non-American governments, supported UNESCO in the development of the “CARE” programme, which sought to help refurnish libraries that lost their collections during the war. CARE funded their book buying, in part, through crowdfunding, again involving the American people. The Louvain library was the first library to receive books through this scheme, but CARE received applications from secondary and vocational school libraries in addition to university libraries and cultural heritage libraries.

The photograph CON_B09765_F001_029 is part of the Louvain library’s greater story of grief, collaboration, and hope. CON_B09765_F001_029 has reminded me that libraries are spaces for connections—both intellectual and personal—for sparking curiosity, and for fostering confidence. The Conway Library, where I was able to uncover this bit of library history, is no different. I feel grateful that the Conway exists to allow students, volunteers, and other researchers to uncover and tell stories. I also feel grateful that libraries have historically been recognized for their stewardship of knowledge and humanity, and I only hope that that trend continues.

Lilly Wilcox

Courtauld Connects Digitisation

University of Oxford

Micro-Internship Participant

* Editor’s note: the box has been digitised however it has not yet to be published on https://photocollections.courtauld.ac.uk/