INTRODUCTION

I turned up on my first day at the Courtauld internship with a pretty clear idea of what I wanted to do: I was going to research and write an essay on the life and times of Etienne Parrocel, a French Painter from the 18th Century who had produced a series of architectural drawings based on his travels in Rome. Parrocel was an accomplished painter, and an interesting man, and I would certainly recommend a google search or scroll though the Courtauld’s digital archives of his works, neatly laid out in aesthetically pleasing vertical rows. I like academic research, have written (many) essays, and was looking forward to week which I expected would probably be not that unlike my last 2 years studying at University.

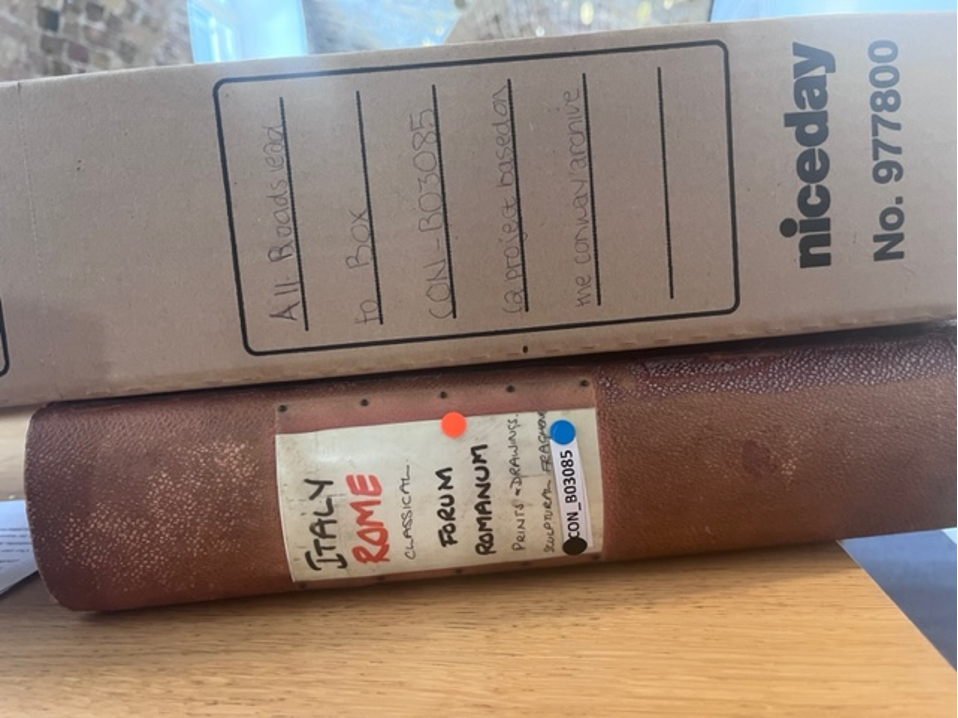

However, as I noisily (and rather embarrassingly) dragged my suitcase down the various steps into the Conway Library, I found myself transported into another world. Much of the Courtauld’s collection is arranged by location, making you feel as though you are in a miniaturised map of the world (or at least Europe). The first place greeting you, appropriately for my interests, is Italy. We all gathered around a small table with shelves of red spines encasing us on all four sides, which felt not unlike the Roman Forum I had been planning to include as part of my research. Front and centre of this display stood Box CON_B03085, its spine emblazoned with ‘Roman Forum: Printings and plans; Sculptural Drawings. Whilst perhaps smaller than the monuments which had once stood in Rome or the Forum, the perfectly accidental placement of this box as this first thing you see in the library, and the aged peeling spine filled me with an almost Romantic sense of awe (although don’t worry, no terrible poetry was penned!).

From this experience, as well as researching the various artists, travellers, and scholars who had made contributions to Box CON_B03085, I wanted to try to recreate for those who have never visited the Courtauld’s libraries – or any archives – what it feels like to make your way through a museum, wind your way round labyrinthine archives, and gradually dig through box. Although it might not normally be seen as a physically demanding activity, it’s not unlike travelling, or archaeological fieldwork itself. I also wanted to think about the ways this has changed from the period when gentlemanly ‘Grand Tours’ dominated how we research – particularly in my field of Classics and archaeology – to today, when people are making efforts through access initiatives and digitisation initiatives (like the Courtauld’s) to increase public engagement with art and museum collections, and diversify access to knowledge.

To help organise these thoughts, I decided to present my research and responses to the images of this box not just in a digital, blog format but by creating my own ‘box’. Usually whilst I am studying for my degree any reconstructions – historical or visual- have to be based strictly on close textual reading or archaeological data. Whilst of course this is necessary when we are trying to reconstruct an accurate view of the past, I found myself inspired by the early modern antiquarians, artists, and archaeologists I was researching during this week to take a more creative, imaginative and personal response to the past. Like the artistic and architectural neo-classical borrowings which inspired those I was researching, I took inspiration from Box CON_ but did not follow its models doggedly. I was also inspired by the Courtauld’s current exhibition on ‘fakes and forgeries’ which I went to visit on the first day, and seeing how in previous epochs the lines between copying and inspiration were more blurred, and not seen as negatively as today.

FOLDER ONE: PRINTS AND DRAWINGS

PRINTS AND DRAWINGS [Click link to open PDF]

The first folder I open in the box is an eclectic mix. It’s labelled ‘prints and drawings’ which hardly does justice to the wealth of material inside. From newspaper clippings, to cut-outs from text books, to various artistic reconstructions and prints of the Roman Forum, the contributors to this box come from a diverse amount of geographical and chronological periods. The order of the box doesn’t make much logical sense either, with different media and time periods all intermixed with each other. The same artists work often isn’t even kept together, with Maarten van Heemskerck’s name greeting me multiple times (probably not a bad thing, as it took me a few times to figure out how to spell). As you sift through this first folder, various sizes of paper drop through your hands, maps are unfolded, text book pages are opened. It’s a very different experience from simply pressing the ‘next’ key on your computer screen. By the end of it I feel as if I know the Roman Forum intimately despite never having been there, experiencing the various physical changes and interpretations it had undergone over 1000s of years through many different eyes.

I wanted to keep my own first folder equally a confusing but hopefully interesting mix of research, photographs, and other types of media. After researching the back ground of the Grand Tour, (a journey round Europe undertaken by many of the artists and photographers included in this box, not the Amazon Prime TV series!), I then researched some of these artists in more detail, their biographies and careers, and made small profiles on them and responses to the specific art works included in this folder. This included Maarten van Heemskerck (1498-1574); George Wightwick (1802-1872); Jean Baptiste Camille Corot (1765-1875); Charles Roach Smith (1807-1890); Charles Robert Cockerell (1788-1863); Israel Silvestre (1621-1691); Mary Beard (1955-); J Hoffbauer (1875-1957); and the Warburg Institute. Their interest in Roman art and architecture sparked art movements like the Renaissance which prized the aesthetic of Greco-Roman antiquities: this fascination continues to today, and is visible throughout London, the capital of another dismantled empire. The Courtauld’s galleries home in Somerset House is replete with neo-classical references, as is the rest of London, showing how to this day we remain inspired by ancient Rome.

FOLDER TWO: SCULPTURAL FRAGMENTS

SCULPTURAL FRAGMENTS [Click link to open PDF]

As an archaeology student, one of the first things you learn is that context is everything. For most of the population, looking at other people’s holiday snaps is universally agreed to be one of the most boring ways to spend time, but for students of archaeology it is one of the most valuable resources, a staple of most of my tutors and lecturers teaching material. That might explain why when I turned up at the Courtauld after 2 months stuck in Oxford looking at all the amazing places I had seen my lecturers go to I was feeling pretty restless. It’s probably unsurprising, then, that despite all the charms of the volunteer room at the Conway Library – unlimited biscuits and coffee, a student’s dream – I pretty quickly got fidgety, and wanted to explore both the wider archive and the beautiful surroundings of Somerset House to contextualise the work we were all doing. After some research, I learned Conway shared a similar passion – as well as being an art critic and collector, he was a passionate explorer and mountaineer, and wrote several books on his travels. Taking this as a sign of approval, I bravely set out beyond the libraries bounds.

The pictures I took on this first afternoon and a few more I took over the next few days are the ones which make up the second half of my project, responding to the folder labelled ‘sculptural fragments’. Unlike the first box where I was researching and trying to understand other people’s responses to public architecture, these pictures reflect what caught my eye, and felt personally resonant or intellectually interesting. I’m no photographer or artist by any stretch of the imagination, and the pictures were taken on my iPhone rather than specialist technical equipment. I definitely took the opportunity to get lost in the archives and the museum and wander where I liked.

The ability to freely explore archives, museums, stately homes, and big cities one I don’t take lightly. In the last few images in this folder are images which show the accessibility – or inaccessibility – of many of the spaces in libraries and museums. Of course, we all experienced this as a collective for almost 2 years during the Covid-19 pandemic, but barriers to knowledge and art continue to exist for many due to financial, physical, or logistical difficulties, which I also tried to photograph. I arranged my photos under themes which emerged from my research on the Grand Tour, and what I probably would have used as chapter headings had I written a normal essay. These themes were Geographical Mobility; New technologies; Accessibility and Inaccessibility; Inspiration and Reconstructions; Maps and Directions; Collection and Storage; and Roman influences back at home.

Inspired by Antonella Pelizzari’s article on the relationship of textuality with photographs, I annotated my print outs with why I took these pictures, and how this linked to my research on the Grand Tour. After doing this, I also decided to hand write my research for Folder One around the pictures I was discussing. Unlike normal essays, this means the mistakes and rewordings I made are recorded for posterity, just like some of the crossings out on the archive boxes. I felt this process made my writing more free and creative than a normal essay I would write, encouraging me to include my own thoughts and creative responses rather than facing the temptation of ‘control F-ing’ my notes, or leaving paragraphs unfinished and going back to them. It also took a lot longer than my normal speed typing, especially as I had to go over all my notes with pen when I got home as it didn’t show up on the scans!

However inconvenient it was, this painstaking process showed that research – whether more informal thoughts from trips abroad, or more ‘serious’ academic library work – is an active, ongoing, and above all human process, which cant be replaced by AI or digital programmes (or, hopefully for my current career plans, at least not yet!). Whilst digitisation is clearly an important move in both heritage and academia industries, and has been beneficial in so many ways I think this experience has shown me that there are limits and things lost for researchers and the general public if we shift entire collections online at the expense of being able to experience the real thing.

CONCLUSION

On the very first page of his work ‘Mountain memories; a pilgrimage of romance’ Conway wrote ‘the landscapes of the past appear at this moment more real than the immediately visible world’. As someone who spends much time exploring places in their head which are far removed by time and place, this sentiment resonated with me. Even after a week of being intimately involved with this box, I’m still not sure why Conway or whoever put this box together chose these images, or put them in this particular order. I’m not even sure if they’d visited the Forum themselves, or – like me- had only experienced its ancient ruins and contemporary settings through a pastiche of other people’s perspectives.

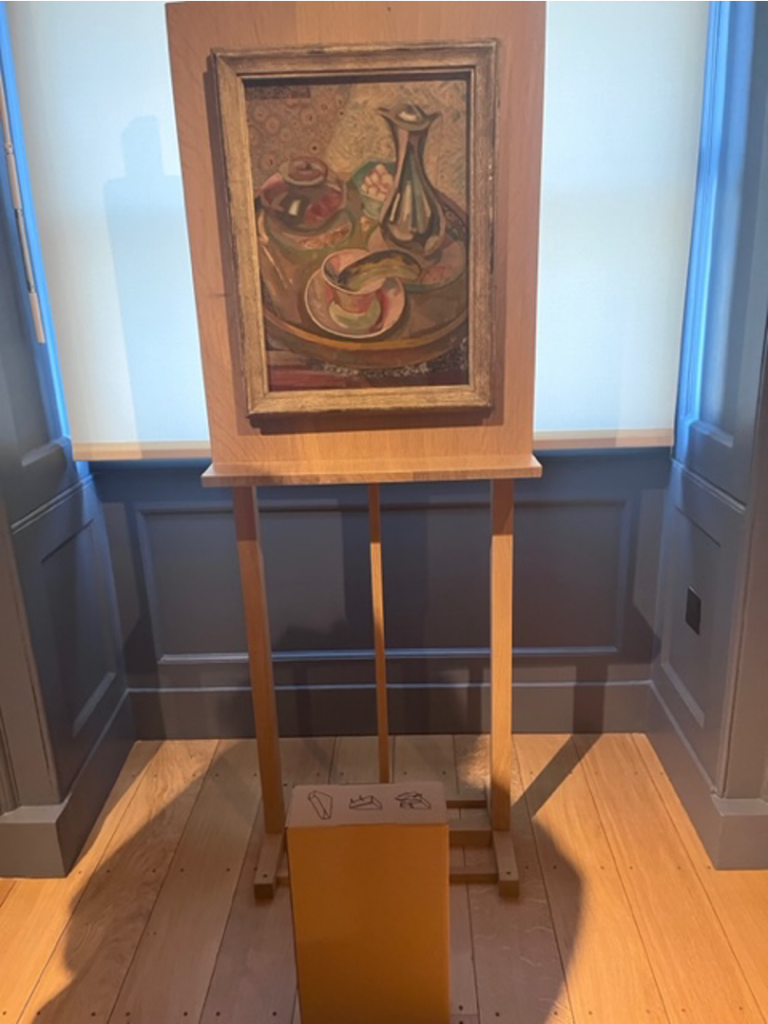

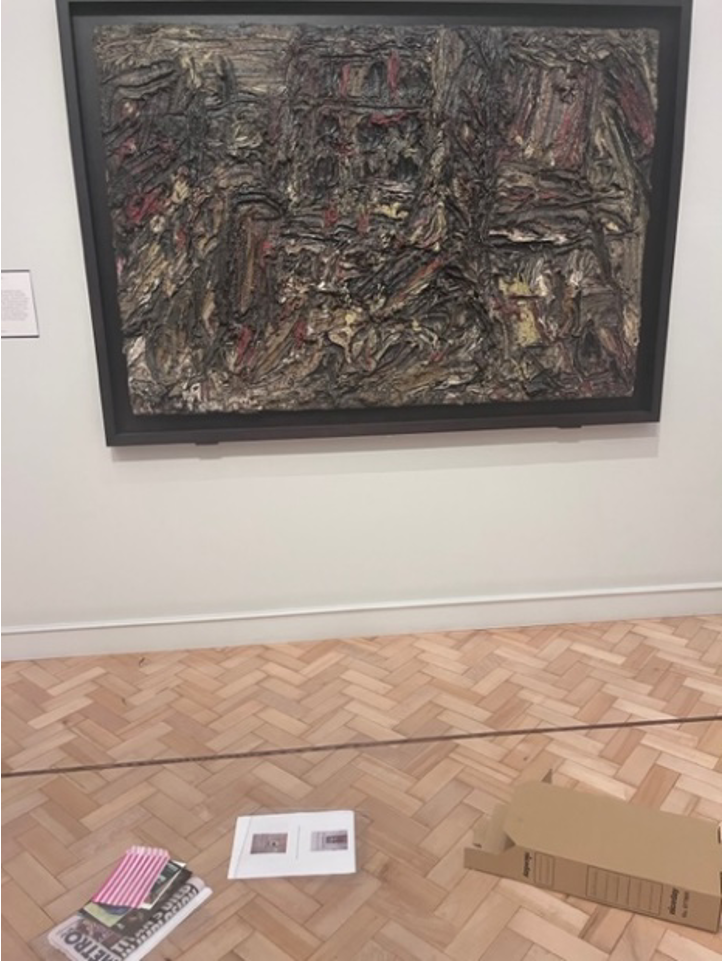

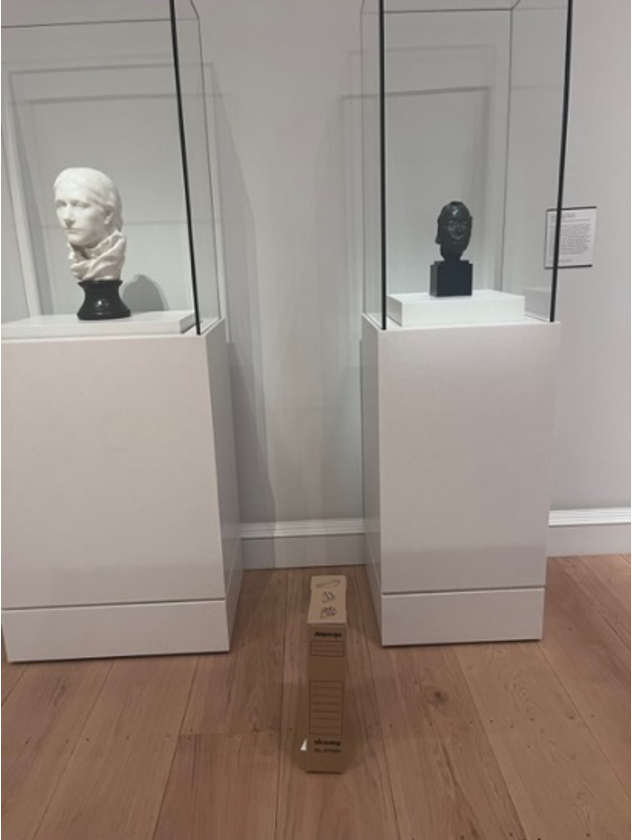

As the final stage in this project, I wanted to bring my box out of the dusty shelves of the archive, into the gallery itself. Many digitisation projects pride themselves on their commitment to accessibility. One of my gripes with this is that outside academic worlds there is a lack of widespread public knowledge that projects and databases like this exist, and most of the public aren’t aware that vast swathes of our archives and objects are not on display, but publicly visible. The volunteer scheme at the Conway library has tried to combat this by bringing those not always familiar with the gallery into the Strand campus, and using platforms like social media also aim to increase public knowledge of these.

It felt silly, and the old box which looked at home in the chaos of the archives looked quite at odds with the sparse minimalistic design of the gallery which prided sleek cleanliness and scholarly contemplation of this gallery – I definitely got some dirty looks from the security guard. At the entrance to the Weston Library – the room at Somerset House containing some of the most famous paintings – is inscribed in untranslated Greek ‘let no stranger to the Muses enter’. A more apt summation of the inaccessibility of classics and many museums in general would be difficult for me to invent. A modern sign opposite translates these words, a signifier hopefully of changing attitudes.

The two main motivations of future heritage projects like the Courtauld’s digitisation project – preservation of memory and widening accessibility – are therefore aptly articulated in the story of the Grand Tour, the Roman Forum, the Courtauld and the Conway and Witt libraries and – hopefully- this box.

IMAGES OF THE BOX

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Antonella Pelizzari 2003, M., ‘Retracing the Outlines of Rome: Intertextuality and Imaginative Geographies in Nineteenth-Century Photographs’ in Picturing Place: photography and the geographical Imagination (eds. Schwartz J. and Ryan J.R.), Routledge, London.

Beard M., 2003, Picturing the Roman Triumph, Apollo vol 158.497.

Black J., 2003, The British Abroad; The Grand Tour in the 18th Century, Sutton, Gloucestershire.

Buzard J. 2002, The Grand Tour and After in The Cambridge Companion to Travel Writing, Cmabridge University press Cambridge, (eds Hulme, Peter, Youngs, Tim)

Chaney E., 2006, The Evolution of the Grand Tour: Anglo-Italian Cultural Relations since the Renaissance, Routledge, New York.

Conway W.M. 1920, Mountain memories; a pilgrimage of romance’, Funk and Wagnalls, New York.

Dyson S.L., Archaeology, ideology, and Urbanism in Rome from the Grand Tour to Berlusconi

Dyson S.L.,2020, The Grand Tour and After: Secular pilgrimage to Rome from the eighteenth to the twentieth centuries, Routledge. London.

Helsted D., 1978 – Rome in Early photographs, History of Photography Vol 2.

Kelly J.M., Reading the Grand Tour at a Distance: Archives and Datasets in Digital History

Levine B. and Jensen K., Around the World: The Grand Tour in Photo Albums, Princeton Architectural Press, New York.

Nilsen M., Architecture in Nineteenth Century Photographs: Essays on Reading a Collection

Salmon F. 1995, ‘Storming the Campo Vaccino’: British Architects and the Antique Buildings of Rome after Waterloo, Architectural History vol 38

Szedgy-Maszak A., 1996, Forum Romanum/Campo Vaccino, History of Photography vol 20.

Amelie de Lara

Courtauld Connects Digitisation

Oxford University

Micro-Internship Participant