The Eastern Orthodox church is famous for its profound veneration of icons – devotional images of Christ, his Mother, and saints. And so, if you find yourself walking, for instance, the heated streets of some Cypriot town, and wandering into one of the local churches just a few minutes before the start of the daily liturgy, all you would hear is a rhythmic succession of kisses. These are the faithful diligently kissing all the icons located along the perimeter of the church, for, to kiss an icon, really, means to kiss the person it depicts.

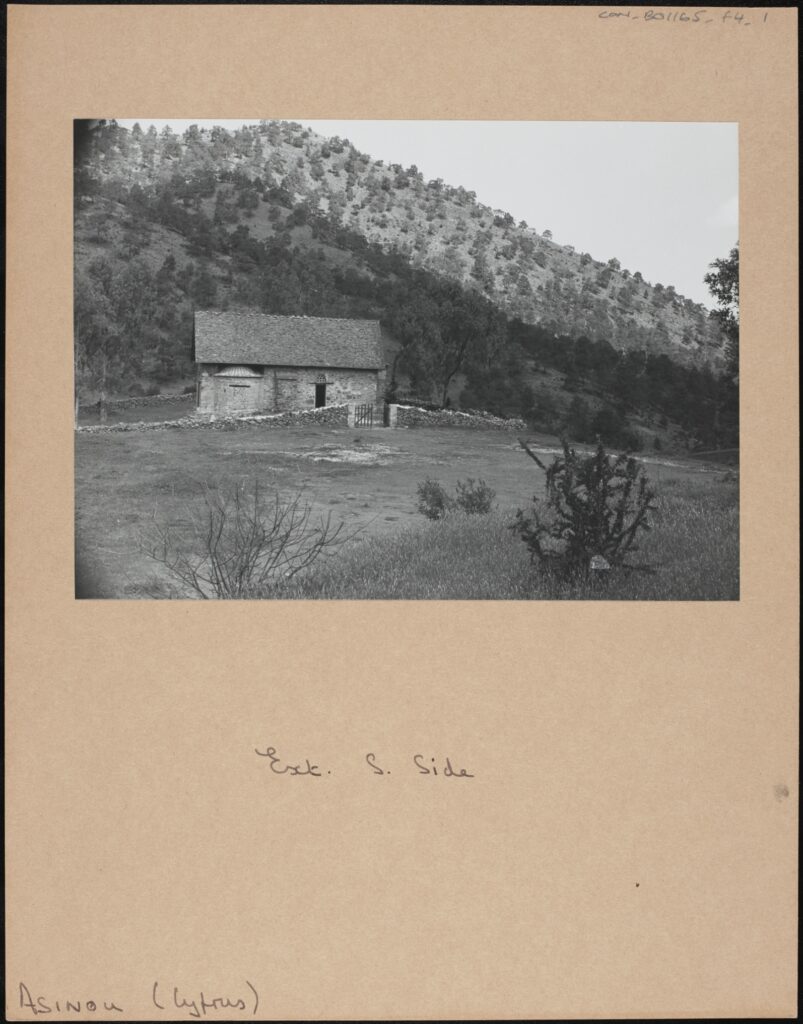

Unfortunately, not all the churches are frequented by the locals. If you are to get into a car and drive through the island for an hour or two, observing the sun-stricken hills covered with dried yellow grass and occasional tanned shepherds with their flocks, and if you manage to follow the map correctly and not get lost along the way, you may reach some of those stone Byzantine churches, lavishly painted inside and looking like clumsy dovecotes on the outside, which are scattered across the countryside, especially in the mountain region of Troodos. Many of them were built and frescoed between the 12th and 16th centuries, although much older buildings also exist.

Fig. 1: South side exterior of the church of the Panagia Phorbiotissa (Panagia tis Asinou) at Asinou, Cyprus. [CON_B01165_F004_001. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

These churches, often once comprising a part of a monastic complex, now appear to stand in the middle of nowhere, with their old wooden doors locked most of the time, and they are usually not used for liturgy anymore. Yet, if you are lucky enough to find a key-keeper, who may also be a priest from the nearest village, wearing long black robes and a serious expression on his face, you would be able to get inside, in order to hear the ‘soundless echo of prayers long silent’ and contemplate the painted walls, ‘alive with worship’, as remarked by an English novelist W. H. Mallock.

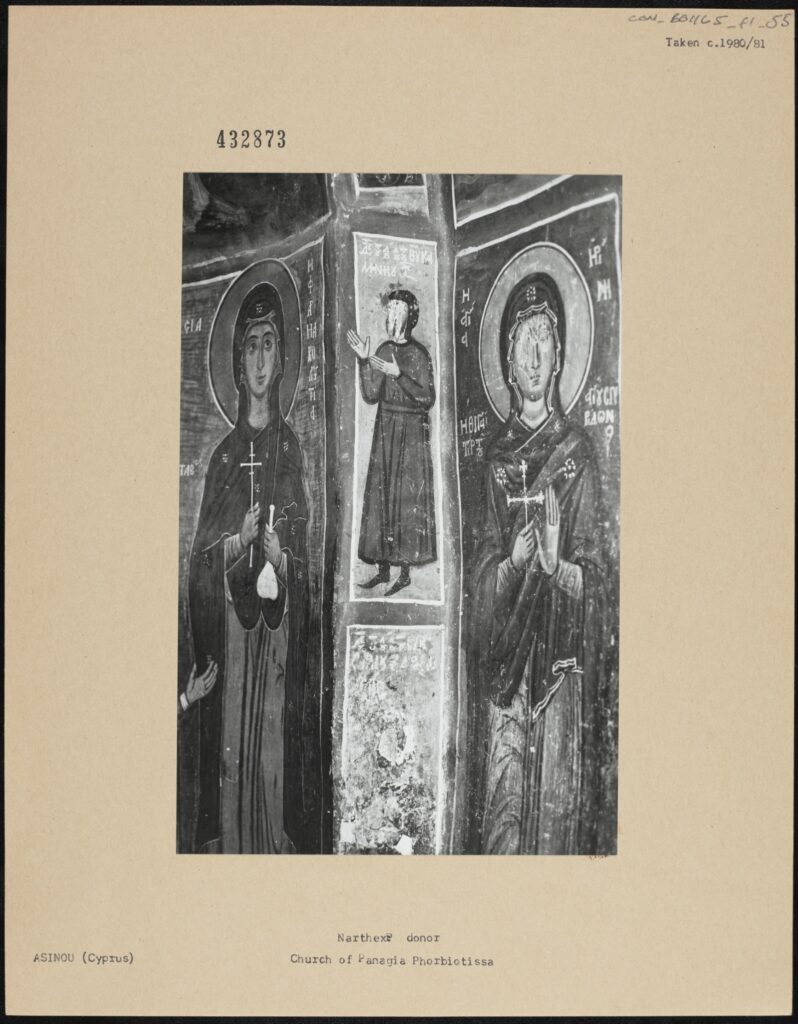

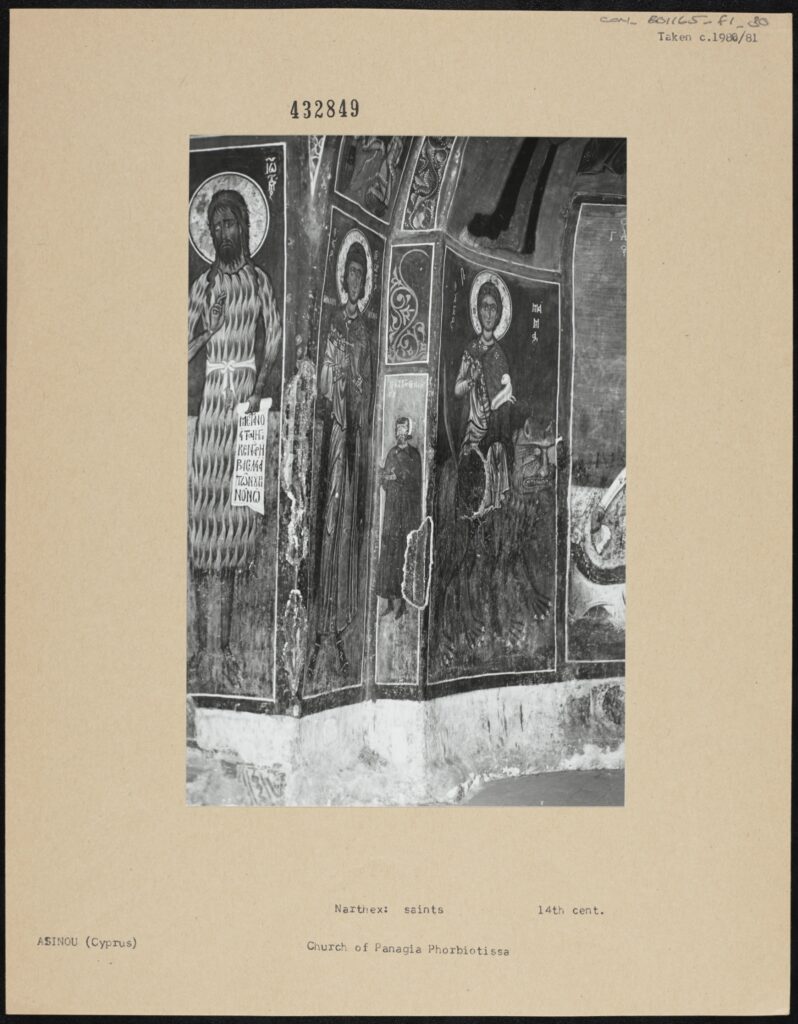

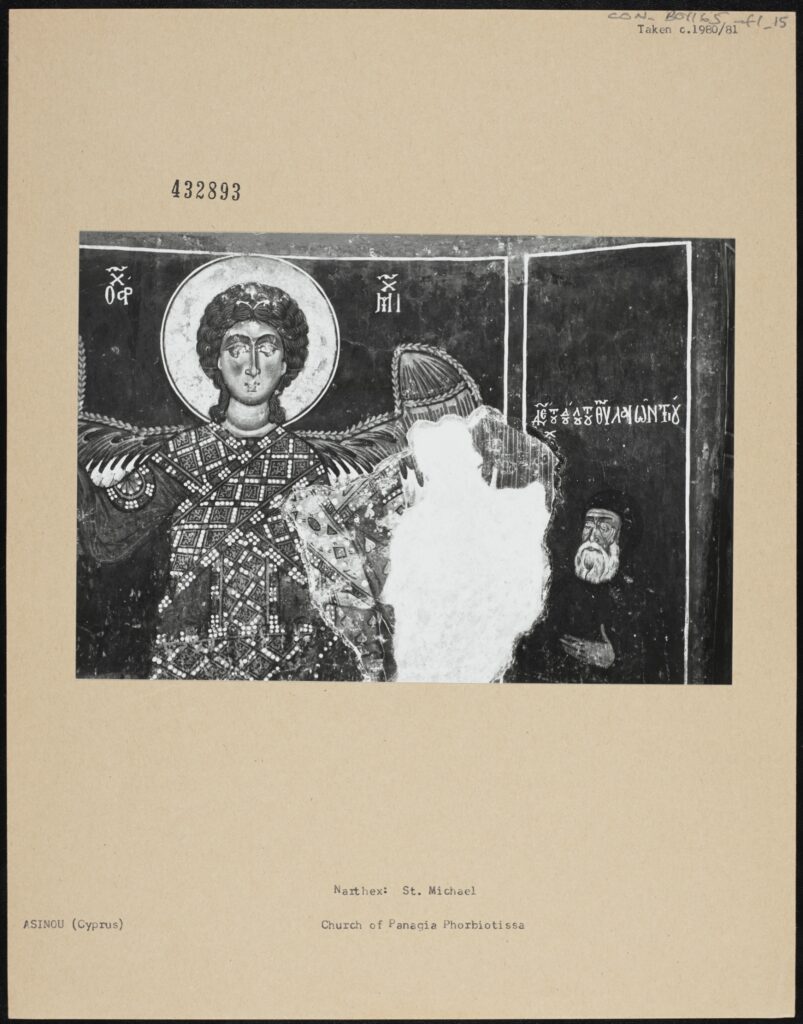

Many of these scattered churches are in a bad condition, with their frescoes damaged by time and the elements, but one of the most striking features is the damage done to many of the faces depicted on frescoes: violent scratch marks, eyes gouged out, and sometimes even whole faces erased.

Below are some examples from the church in Asinou (fig. 1), but a similar situation can be encountered all across the island.

Fig. 2: Narthex: donor and female saints, Church of Panagia Phorbiotissa, Asinou, Cyprus. Taken in 1980/81. [CON_B01165_F001_055. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

Fig. 3: A detail of: Narthex: saints, 14th century, Church of Panagia Phorbiotissa, Asinou, Cyprus. Taken in 1980/81. [CON_B01165_F001_030. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

Fig. 4: A detail of: Narthex: St Michael, Church of Panagia Phorbiotissa, Asinou, Cyprus. Taken in 1980/81. [CON_B01165_F001_015. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

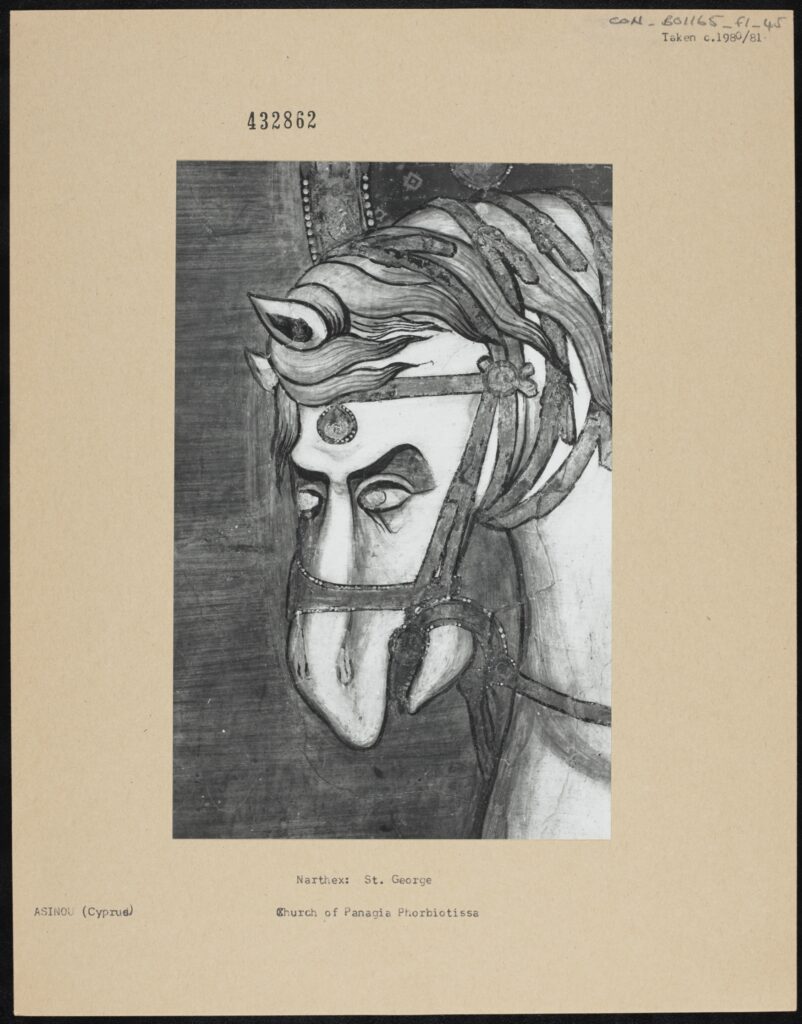

Fig. 5: A detail of: Narthex: the horse of St George, Church of Panagia Phorbiotissa, Asinou, Cyprus. Taken in 1980/81. [CON_B01165_F001_045. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

A question naturally arises as to who did this and why, and if you were to ask the priest who let you into the church, or some other elderly Greek-speaking Cypriot taking care of the place, you will receive one and the same reply: ‘this was done by the Muslim Turks’. Now, the island was conquered by the Ottomans in 1571 and remained under their rule until 1878, when it was passed over to the British. During that time two major communities were formed in Cyprus: that of Greek-speaking Christians, and that of Turkish-speaking Muslims, which coexisted with different degrees of peacefulness. However, in 1974, less than fifteen years after Cyprus announced its independence from the British rule, the country fell into war and split into Northern (Turkish), and Southern (Greek) parts, remaining divided to this day. Therefore, the attribution of the blame to the ‘Turks’ is natural, considering the interreligious animosity and alleged Muslim reservation towards religious imagery, but such a claim may be motivated more by political bias than by truth.

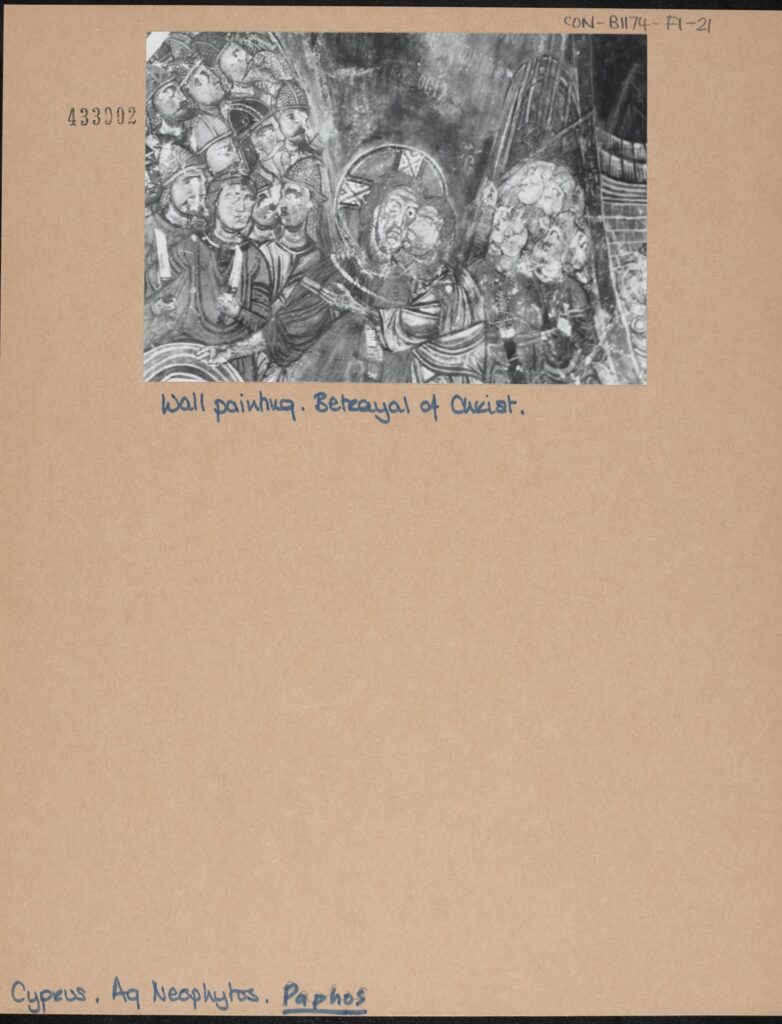

The issue has not yet been properly researched, but some other theories are floating in the air. Some say that the eyes on frescoes were destroyed by robbers or looters, who did not want to be ‘seen’ while committing their criminal deed. Others point to the tradition of taking some paint off a saint’s eye as depicted on a fresco in order to make a healing mixture, which is especially good for eye diseases. This is primarily attested in the Troodos region, as well as on the island of Crete. Further to this, there are examples of damnatio memoriae (‘condemnation of memory’) – erasure of the depiction of devils and sinners. An example of this can be found in the monastery of Agios Neophytos, where on a wall painting depicting Jesus betrayed by Judas and surrounded by Roman soldiers, the eyes of the soldiers and the betrayer are systematically gouged out (fig. 6).

Fig. 6: A detail of: Wall Painting, Betrayal of Christ, Agios Neophytos, Paphos, Cyprus. Taken by Neil Stratford. [CON_B01174_F001_021. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

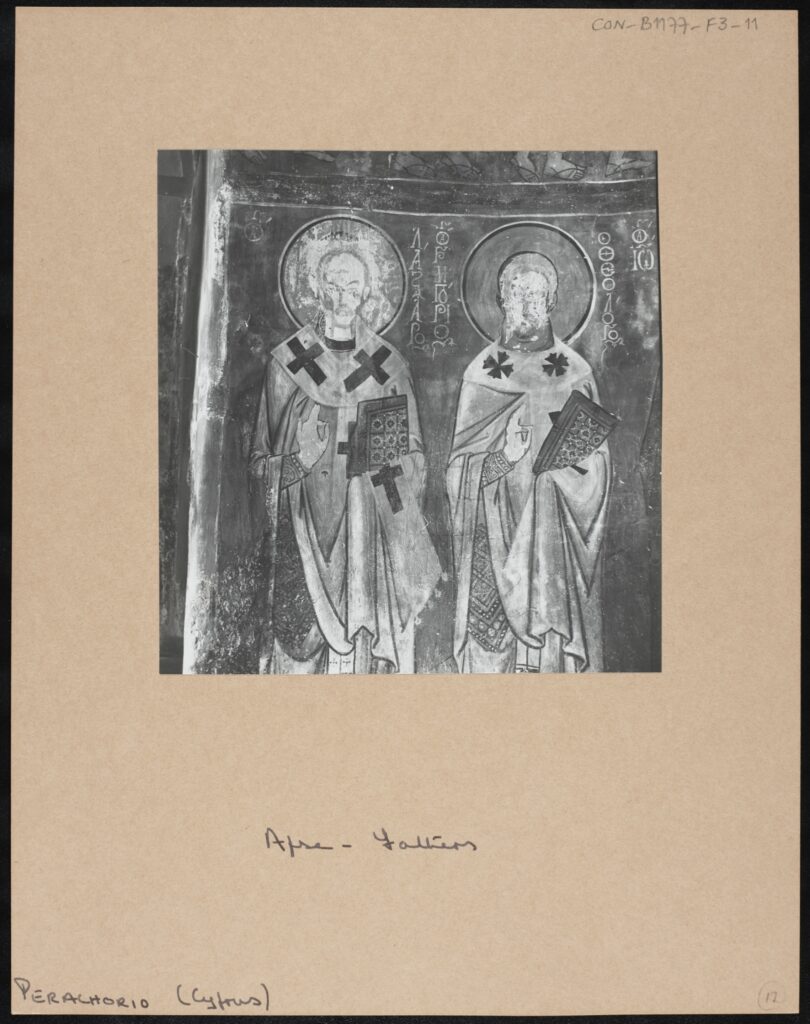

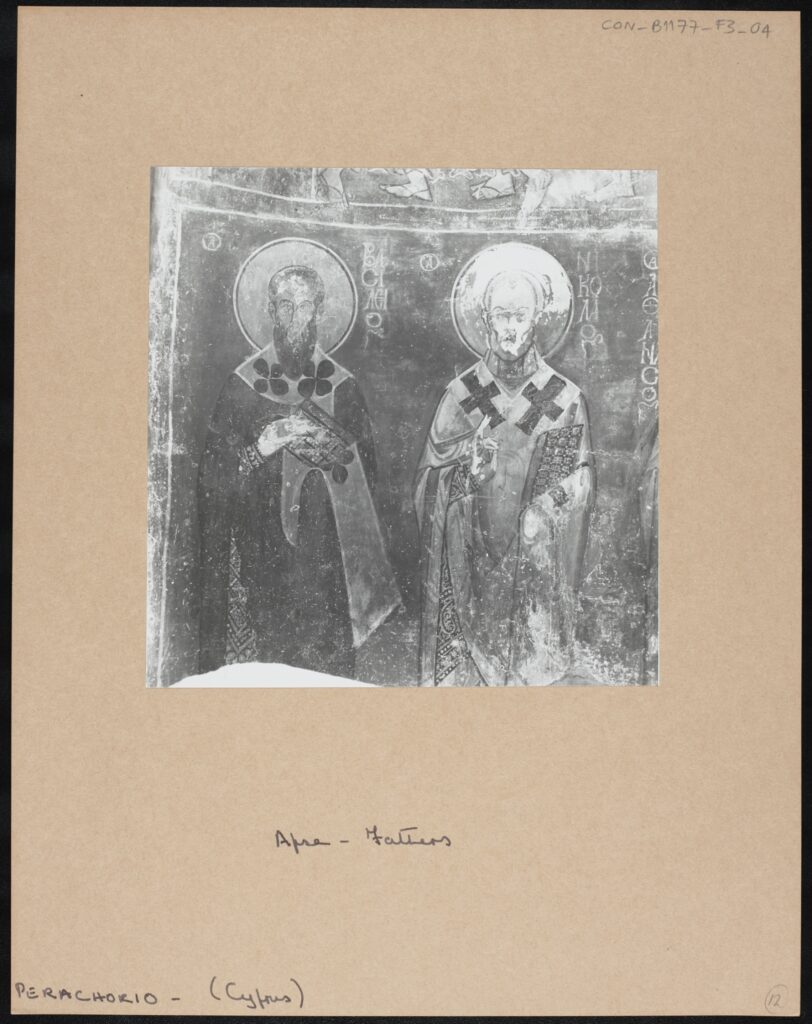

In other cases, as mentioned, the whole area of the face is affected.

Fig. 7: A detail of: Apse – Fathers, Church of the Holy Apostles, Perachorio, Cyprus. [CON_B01177_F003_011. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

Fig. 8: A detail of: Apse – Fathers, Church of the Holy Apostles, Perachorio, Cyprus.Taken by David Winfield. [CON_B01177_F003_004. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

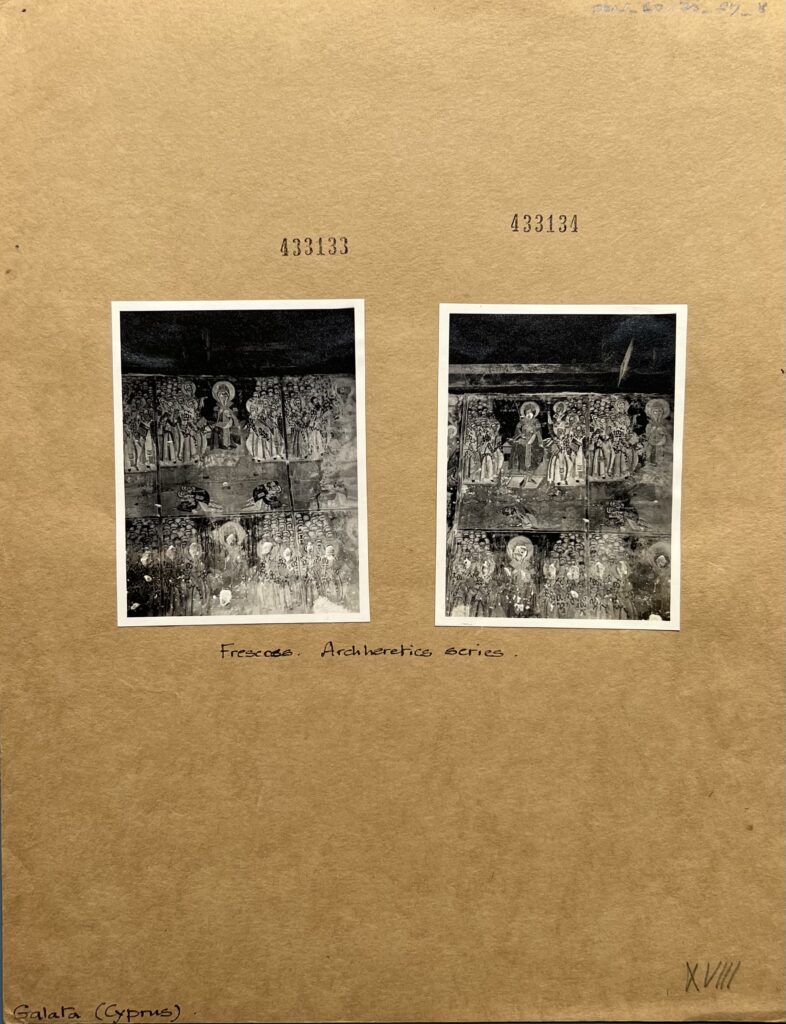

Fig. 9 and 10: Two details of: Frescoes, Arch-heretics series, Agios Sozomenos, Galata, Cyprus. Taken by CJP Cave. [CON_B01170_F007_008. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

So, what is so special about the eyes, and the face more broadly, which attracts the efforts of iconoclasts? The face is the locus of one’s identity, the eyes – the medium of seeing and the sign of being seen. It is through the face and especially through the eye contact that one connects with another person and receives recognition.

Now, in the realm of Eastern Orthodox iconography this acquires further significance, for contemplation and veneration of an icon is at its heart a face-to-face encounter – between the believer on the one, human side of the painted surface, and the holy person, on the other, spiritual side. The obliteration of the eyes/face thus makes the encounter profoundly obstructed, if not impossible, for it erases the very thing which serves as a mark of presence – a face directed at you, with eyes wide open.

It would be interesting to note here one characteristic iconographical convention, namely, that only sinners can be portrayed in profile (see fig. 6 with the scene of the betrayal of Jesus), whilst saintly people must always be depicted with both of their eyes being visible, preferably en face. This brings us back to the eye contact being the means of encounter, which the iconoclasts wanted to prevent, for one reason or another.

And so, these churches stand, full of mystery and history, their walls bearing marks of lips that kissed them, of smoke coming from numberless candles once burnt inside, of hands that touched them, whether caressingly or violently, of the painter’s brush traced on the wet surface centuries ago, and of the iconoclasts’ instruments applied to, quite literally, deface the images, combining to create a multi-layered record of the complex history of the island and its communities.

Alina Khokhlova

Courtauld Connects Digitisation

Oxford University

Micro-Internship Participant