During my internship at the Conway Library, I focused on finding photographs of damaged art, specifically sculpture and stained glass. What follows are three poems I wrote on what I found to be the three most interesting of these images. After this is a discussion of these pieces, examining their historical background and their worth as damaged pieces of art.

Poetry

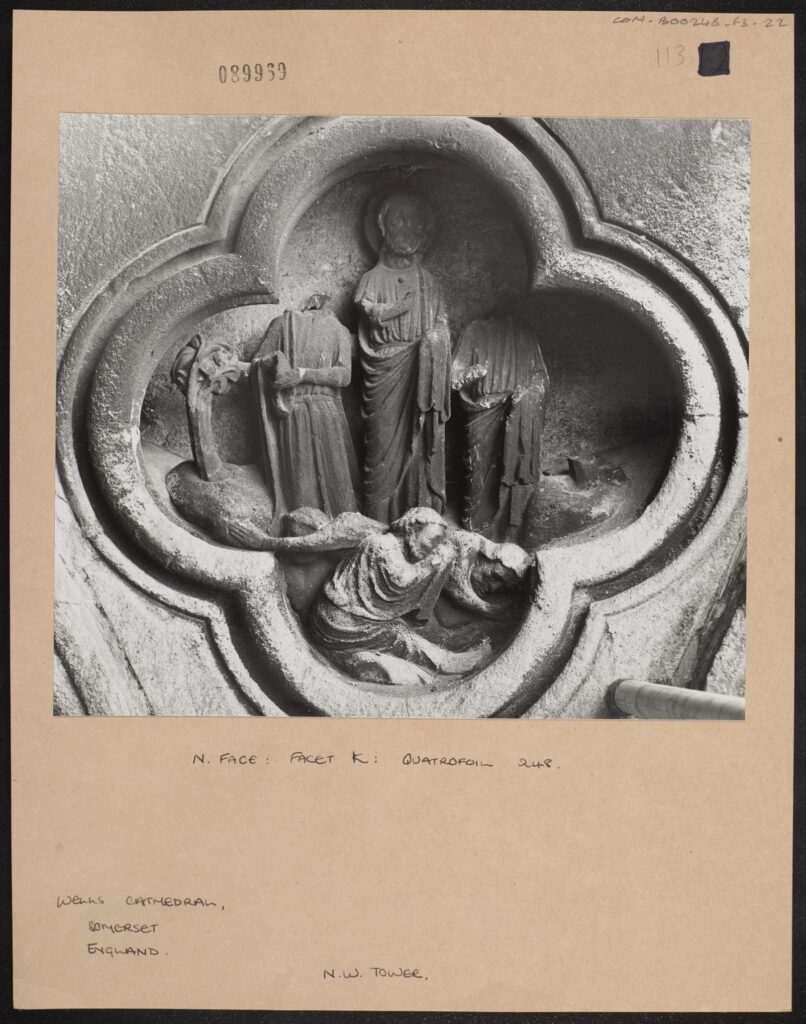

A close-up, black and white photograph of a clover shaped recess in a stone wall, known as quatrefoil 248. [CON_B00248_F003_022 – ENGLAND, Somerset, Wells Cathedral. North face, facet: K, quatrefoil 248, N.W tower, N side, pre-restoration. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

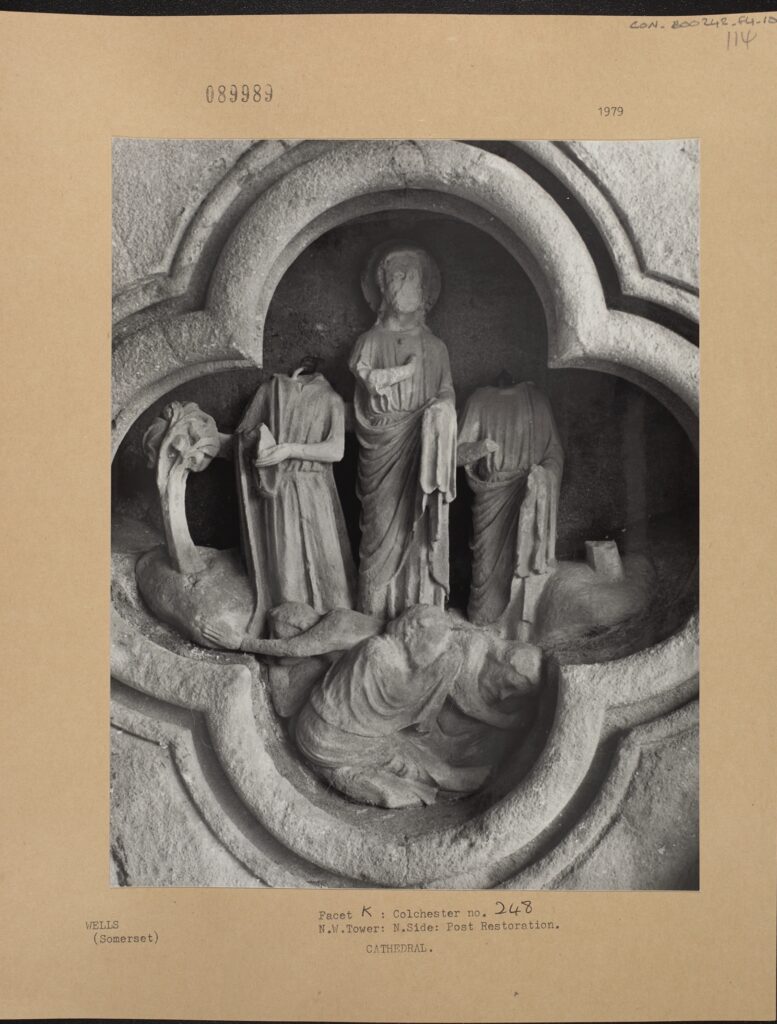

A close-up, black and white photograph of the same quatrefoil pictured above. The images are almost identical. [CON_B00248_F004_010 – ENGLAND, Somerset, Wells Cathedral. Facet: C, Colchester no. 248, N.W Tower, N side, post- restoration. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

Wells

I was brought into creation,

With my brothers,

We three standing proud,

Brought beneath us,

Were those others,

Who curl their faces to the ground,

Beneath our feet,

I call to them, “Men,

Why don’t you rise?”

They shudder softly and say,

“You will see, when,

The outside takes your eyes.”

My brothers told me not to listen,

To men who feared the sun,

“We were created by the righteous,

See how they look on us with awe,

Brother this is our dominion,

Nothing here will slight us.”

For many years we stood,

With prideful benevolence,

For the men who cried below,

Until my brother’s hand lost,

Its finger, the severance,

A creeping blow.

“You are marked a sinner,”

Boomed my brother with hand intact,

We saw it as a punishment,

“But please, brothers, I do not know,

What I did or what I lacked.”

We did not doubt His judgement,

And those beneath us howled,

As we froze and shunned,

Our kin with his sinner’s mark,

They implored us,

“Don’t let yourselves be numbed,

Don’t let the outside take your heart.”

When my brother’s ears,

Started to fall away,

He turned his accusation downwards,

To the “whimpering, conniving hoard,

Who crouch as though to pray,

But feed the devil broken shards,

Of flesh taken from the holy.”

The grovellers tried to protest,

But my brother knew sound no longer,

And he could not hear them say,

That “the outside will not rest,

Until none of us are what we were.”

I begged forgiveness from my brothers,

For standing tall while they withered,

But only one could hear my sorrow,

And he was the one whom we had wronged,

And though I know his lip quivered,

He let no emotion for me show.

A storm took the head of my brother,

He who had squalled against sin,

And as we wailed those hateful,

Soothsayers said loud,

“We told him he would not win,

Against the outside’s great pull.”

My brother came to forgive me,

While we cried for our lost,

We cursed the snivellers in their hole,

For they had committed the crime,

Of being unblemished at the cost,

Of our dear brother’s soul.

My nose had vanished by the time,

My second brother lost his head,

And I hated the cowards keeping their secret,

Of how to remain whole,

“Why is it they are dead,

While you men meet no threat?”

“We warned you to fear the outside,”

They admonished me hard,

“You thought yourself an equal,

To its power,

You let your brothers disregard,

That which comes before the fall.”

“But how can I not stand tall!

When my creator made me so?”

They hid their answers undercover,

And so I aimed my question out,

“Oh creator, did you know,

That you built us only to suffer?”

I received no answer,

But eventually there did appear,

Disciples with wands of creation,

I could have collapsed with joy,

That they would restore what was dear,

I would cease to be a family of one.

They brought potions to clean our bodies,

Cracks they took days to restore,

But they did not return my brothers,

And when I tried to scream and beg,

I found that I had a mouth no more,

And all my noise was smothered.

I faced my recreation,

With corpses by my side,

I wish I did not see their degradation,

But the outside never took my eyes.

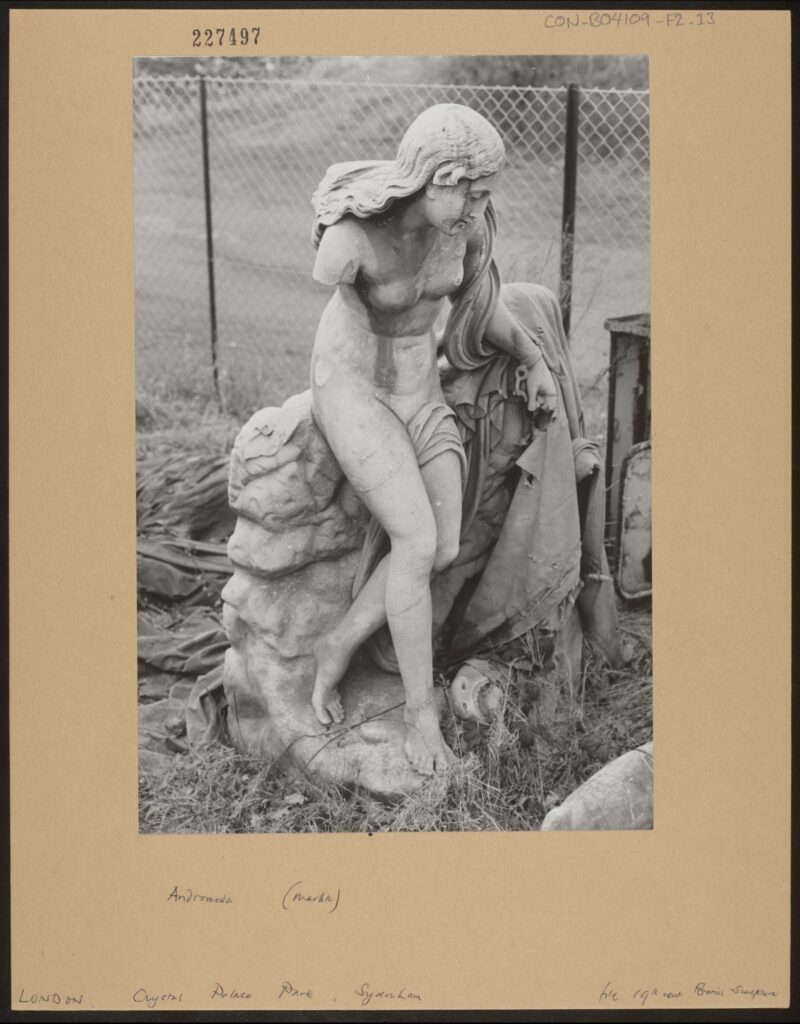

A black and white photograph of a neo-classical sculpture in marble, depicting the Ancient Greek mythological figure Andromeda. [CON_B04109_F002_013, ENGLAND, London, Sydenham, Crystal Palace Gardens. “Andromeda”. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

Andromeda

She was chained to a rock in the ocean,

Waiting for him to come,

Blinded here by the sun’s reflection,

Blinded so that she cannot remember,

Why it is that she is here,

What she did to deserve such a punishment,

As being a feast for so many monsters.

She was chained to a rock in a house of glass,

Waiting for him to come,

Stares remind her that she is frozen,

With hands that cannot cover and eyes that cannot close,

She doesn’t know if it is part of her punishment,

Being up here on display,

A feast for so many monsters.

She was chained to a rock in the ashes,

Waiting for him to come,

Hands frozen she cannot wipe away,

The soot that clings to her,

Or the weeds that grow through the cracks,

She wonders when it was she was forgotten,

Whether it is a mercy to be here alone,

And she still cannot remember what it is that she did,

To have been the prize of so many monsters.

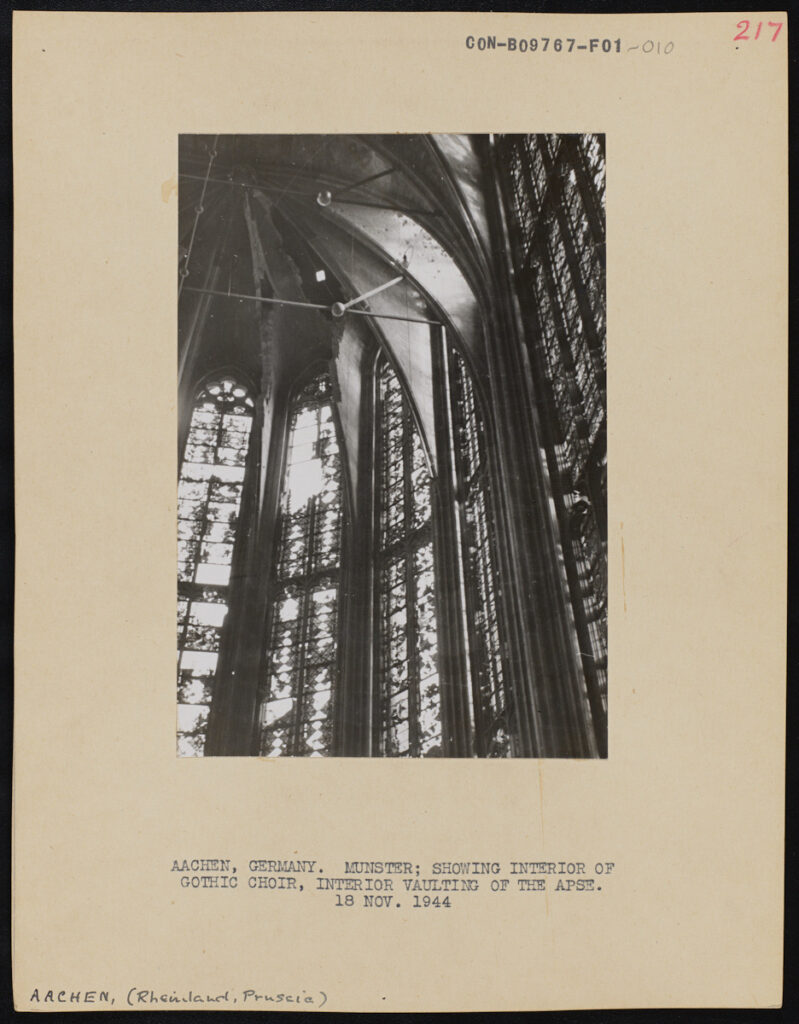

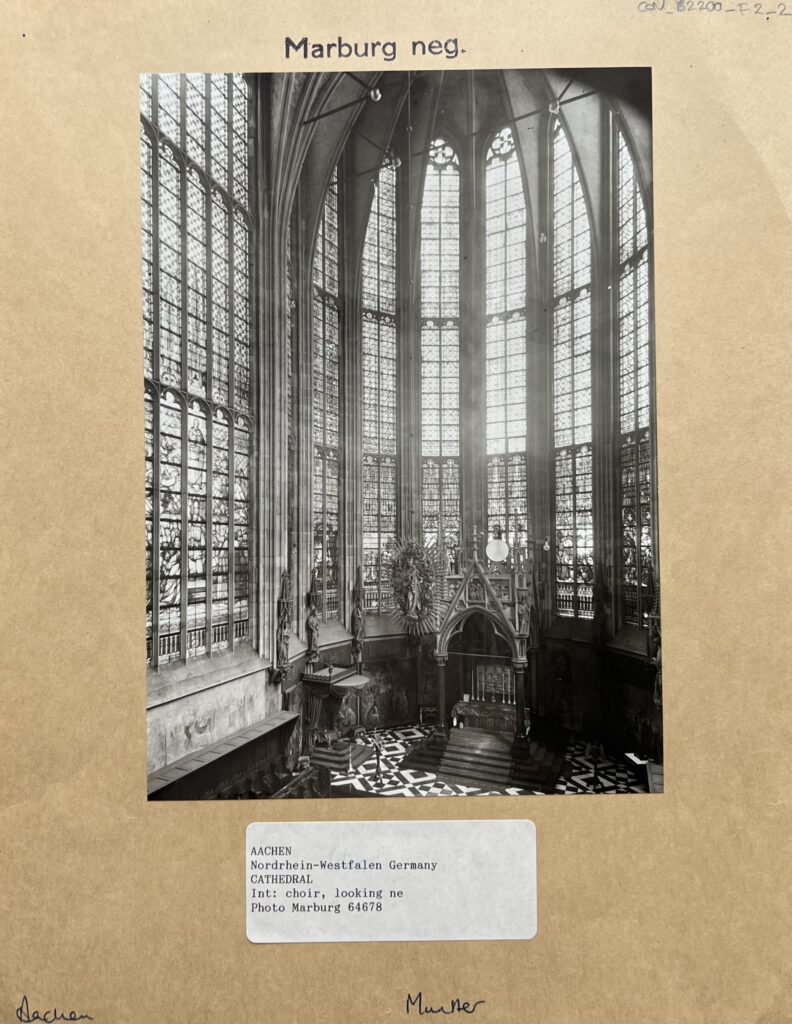

A black and white photograph mounted on card depicting the interior of the choir of Aachen Cathedral. [CON_B09767_F01_010 – GERMANY, Aachen, Munster. Showing interior of Gothic choir, interior vaulting of the apse. 18 Nov. 1944. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

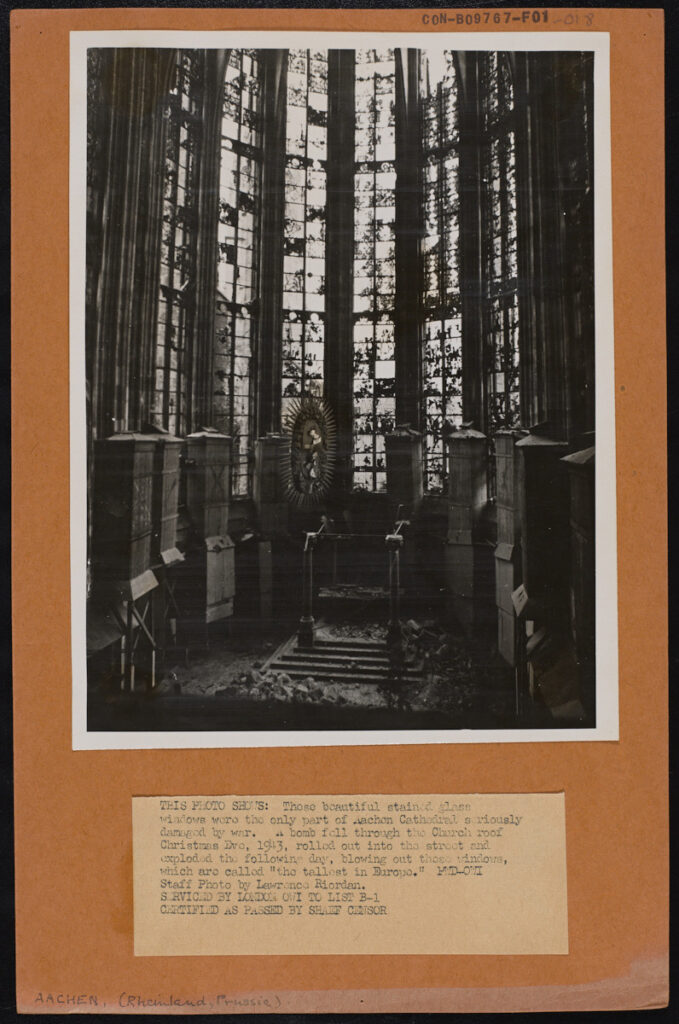

A black and white photograph mounted on card. Caption: “Those beautiful stained glass windows were the only part of Aachen Cathedral seriously damaged by war. A bomb fell through the Church roof Christmas Eve, 1943, rolled out into the street and exploded the following day, blowing out those windows, which are called “the tallest in Europe.” [CON_B09767_F01_018 – GERMANY, Aachen, Munster. Showing the damage of the stained-glass windows in Aachen cathedral’s choir. Attribution: Lawrence Riordan. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

Aachen

The bombs are dropping and we’ve been left behind,

Too large to move, not worth it,

Shaking in our panes,

As the world falls to pieces.

The ground is being torn up,

Every friendly thing made a projectile,

The city is being warped into weaponry,

To be turned inward on itself.

An arrow through Peter,

That once was a branch,

A bullet through Matthew,

That once was a stone,

And Mary holds her child tightly,

But is no shelter from the cannonball,

That once was a chimney-pot.

So far above, do they look down,

And see the slaughter they’re unfolding?

Or are they shielding eyes and ears,

Minds never here at all?

So far above they won’t ever know,

How Jesus’ body shattered.

The morning is come and they are gone,

But the sun doesn’t halt its rising,

And if you in the rubble were to stop and look,

You would see sunlight unfiltered,

Where once was red and green and blue,

And if you were to stop and see you’d know,

That splinters of glass look smoother when warmed with gold.

And we are gone to dust on the floor,

But the sun sees us clear,

And the cowering relics turn their heads,

Never having known a glow untainted by us.

And if you were to find them, miles away,

Watching homes burn and counting their dead,

Would it bring them relief or rage to know,

That what they did let the light come in?

Discussion

I wrote the above poems while examining three photo sets from the Conway Library, all showing art that had been variously damaged. What fascinated me about the pieces was that, despite being disfigured, they were all enthralling. They had inspired photographers to capture them, and they had inspired me to write about them. Would it be unfair to say then that their damage decreased their artistic value?

In the course of my week at the Conway I have researched these three photographic subjects and have here compiled short histories of each. I hope that in understanding the subjects the true impact of their being damaged may become clear.

Wells Cathedral

To begin with the subject of the first poem, a small group of carvings within a quatrefoil at Wells Cathedral, Somerset. They sit on the north face of the north-west tower of the cathedral’s magnificent west front and constitute one of many quatrefoil carving groups on the cathedral. This cathedral, along with its carvings, is medieval, having been built between the 12th and 15th Centuries, with the west front probably being completed in the 13th Century. It is the first English cathedral to have been built in the ornate Gothic style in which intricate carved representations of biblical stories were common.

The subject here is the Transfiguration of Jesus, a New Testament story in which Jesus (here carved in the middle) begins to glow with heavenly light (represented here by a halo). He is visited by the prophets Moses and Elijah, who here stand on his either side. The figures cowering below him in the carving represent his disciples, Peter, James and John, who were praying with him at the time of the transfiguration and were overwhelmed by what they were witnessing. The story is given particular theological importance by the voice of God, which here referred to Jesus as his son and bade all to listen to him. That this element of the story is not represented here is presumably due to the difficulty of depicting a vocal address in a carving, and it was likely assumed that many viewers of the group – if indeed they could see it properly from the ground – would know the Transfiguration story.

The carvings as seen in the first photograph were heavily damaged due to the simple face of having been exposed to the elements over time. What is more interesting is that the second photograph shows them after having been restored during a massive west front restoration project in the 1970s. My first thought when seeing this second photograph, was that the carvings look hardly changed from how they had been prior to having been restored. The heads of the prophets are still missing, but more striking to me is that the face of Jesus is still worn away, none of his features having been redefined.

Further research led me to summaries of the restoration work from which it was clear that the goal of the work was simply to clean the work and preserve its present state, with no aim to restore the original appearance. That the restoration had these purposes is revealing of the changed way in which we in the modern era interact with medieval Cathedrals compared to those in the time in which it was built. While in the Middle Ages the aim of such carvings seems to have been to represent bible stories, perhaps with the intention of teaching parishioners or perhaps out of some reverence to God, now it does not seem to be of much relevance whether the story is legible.

Indeed, some of the quatrefoil carvings were so damaged that one could only guess as to what they had been. When people now come to visit historic churches such as this, the interest for many is either in the history or the aesthetic beauty of the place. Even those visiting for religious reasons may be more interested in seeing the authentic expressions of faith of those 13th Century workers, increased literacy meaning there is less of a need for the bible to be told in visuals. There is an argument to be had that to repair the old carvings with modern additions, even if they look as close in style as possible to the original, would be to detract from this authenticity and, as Carolyn Korsmeyer puts it, to commit an act of ‘aesthetic deception’.

There is definitely an element of the Ship of Theseus debate in such a line of thought and, like this philosophical conundrum, there is no agreed upon correct answer. At York Minster, for example, the permanent stonemasons yard carves new grotesques to replace those adorning the minster’s exterior when they become damaged. Evidently it is the consensus here that retaining the appearance of the stonework is more important than retaining its genuine historical elements. At Wells Cathedral, the damaged state of the figures is preserved – the effects of the elements over the years have shaped the carvings into something new which is considered worth saving.

Andromeda, Crystal Palace

The sculpture of Andromeda from the Crystal Palace has an entirely more dramatic, and ill- fated, backstory. The sculpture is neo-classical in style, probably made between about 1760- 1860 when the fixation on the classical age was at its peak in Britain.

The story it represents is the Greek myth of Andromeda. In this story Andromeda, the princess of Aethiopia, is chained nude to a rock in the sea as food for a sea monster. Her punishment was not at the result of anything she did, but a response to a claim her mother made that her daughter was more beautiful than the Nereids. Poseidon, father of the Nereids, found murdering Andromeda to be a fitting revenge. In the story she is saved from her fate by Perseus, who slays the sea monster and carries Andromeda home to Argos to be his queen.

With no available information about the sculptor of this work, it is difficult to guess at why exactly the myth of Andromeda was chosen as a subject. But this certainly wasn’t the only example of a neoclassical depiction of her and comparison to others, particularly the 19th Century Italian work by Romanelli, suggests that the obscured object at her feet to the right, is the broken head of the sea monster which was originally shown circling her.

A colour photograph depicting a white marble neo-classical sculpture of the figure from Ancient Greek myth, Andromeda, on a black background. A naked female figure, draped in cloth, is shown chained to a rock, the head of a sea monster rising up from sculpted waves below, as if to bite her. She raises her free hand up above her head, her mouth slightly open in shock and fear. [ITALY, Florence. “Andromeda”, sculptor: P. Romanelli, 19th Century. Attribution: Sotheby’s auction catalogue.]

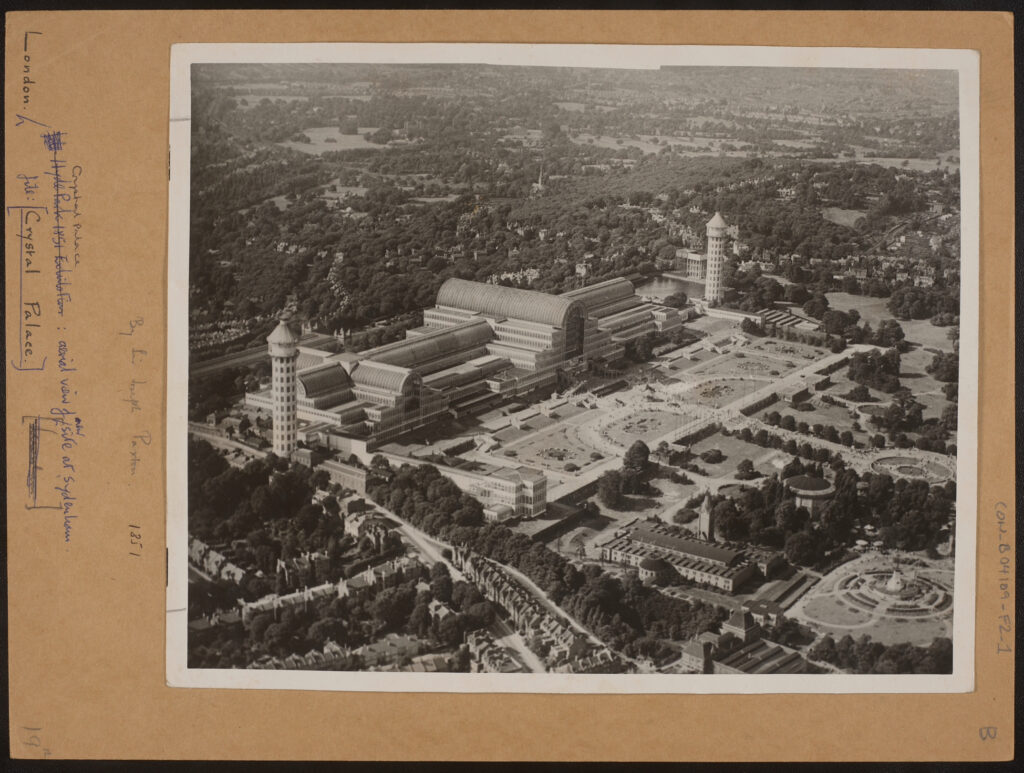

This sculpture was one of many artworks that had its home in the Crystal Palace, the grand glass Victorian structure which stood originally in Hyde Park, where it was built to house the Great Exhibition of 1851, after which it was moved to Sydenham.

A black and white photograph depicting the Crystal Palace in Sydenham, London, from the air. [CON_B04109_F002_001 – ENGLAND, London, Sydenham. Aerial view of the Crystal Palace, Sydenham. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

In Sydenham it reportedly struggled to attract visitors, despite its large collection which included British sculptural works such as this one. Its ultimate fate was to be destroyed almost entirely by a fire in 1936 (the cause of which was never determined) with its final remaining tower structures being pulled down during World War 2 and its gardens been left in disrepair.

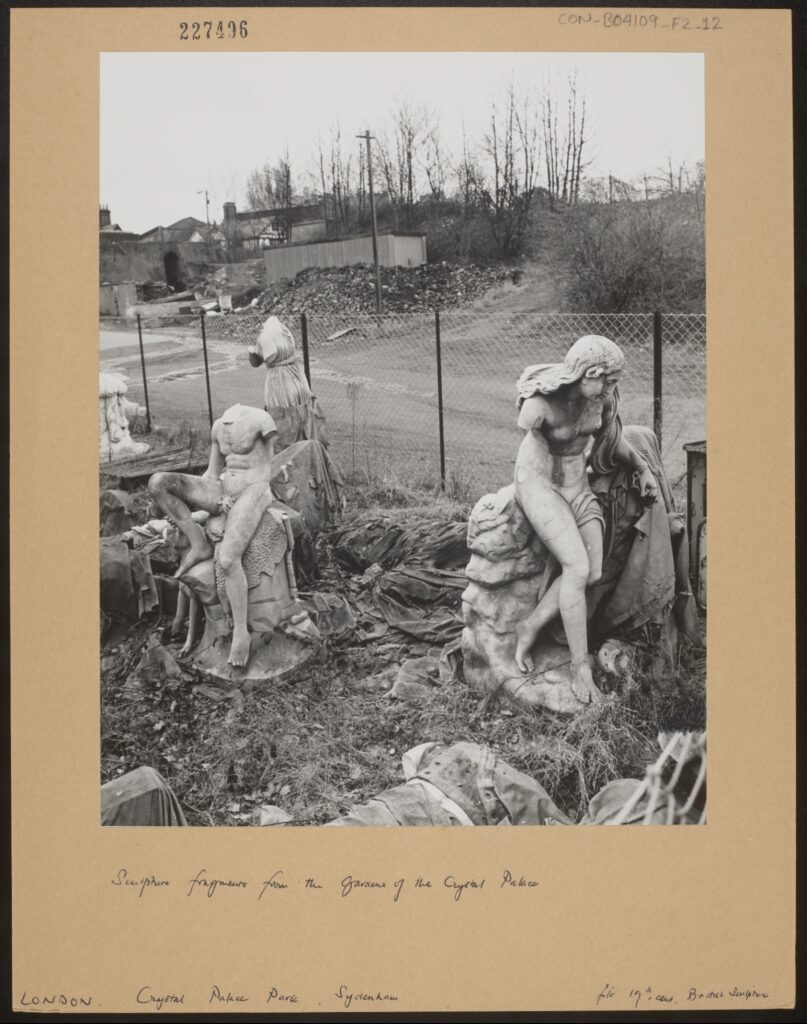

This photo of the forgotten Andromeda was taken in the 1970s, decades after the fire. Another image taken at the same time shows that she was stood in a cluster of similarly abandoned neo-classical sculptures, many of which miss limbs and heads. It is difficult to know whether she was inside the building when it burnt, some sculptures being designated for the Palace’s gardens. A comparison to other fire-damaged marble statues has suggested to me that the black stain across her torso is consistent with her having at least been close enough to the flames to have been scolded by them.

A black and white photograph of abandoned sculpture fragments in the gardens of Crystal Palace. To the right is the aforementioned Andromeda, these two photographs were likely taken at the same time. To the left of the photograph, three other fragments are visible. [CON_B04109_F002_012 – ENGLAND, London. Sculptures in the Crystal Palace gardens, Sydenham, 1970s. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

Why then was Andromeda deemed worthless while the Wells carvings were preserved? Part of this will be a question of age, medieval carvings being older and so considered more valuable than neo-classical. One can be sure that, had this sculpture been genuine Graeco- Romano, she would not have been left to be broken by vandals. Another is probably a simple question of finances. Those with vested interest in the Crystal Palace would have suffered an immense blow when it was destroyed and the cost of repairing and transporting a minor, now damaged, artwork from within it probably was not worth the hassle. The final point is one of context. The Wells carvings have the benefit of being both religious in nature and attached to a historically significant building.

As such, as long as there is still a clergy at Wells Cathedral, and tourists coming to admire it, there will be incentive to prevent their further decay. A sculpture from a completely destroyed building, in a style typically associated with the vanity and pretentious tastes of Europe’s aristocracy, has less protection.

The current fate of our Andromeda is not known. The only reference I could find to her was a 2007 contributor on an online forum dedicated to Sydenham who claimed that the Andromeda ‘lost her head!’ since the 1970s image. Whatever her exact present state, it is clear that Andromeda was abandoned by those who had decided to display her in the Palace.

Aachen Cathedral

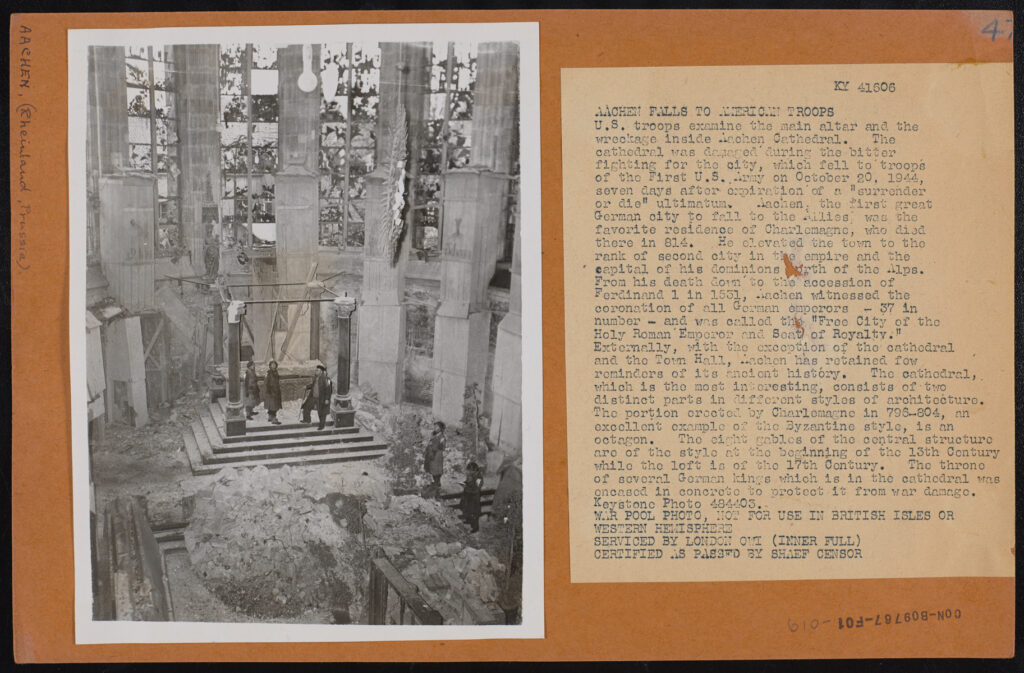

The final set of images was taken of Aachen Cathedral after the western German city fell to the American forces in 1944. It was the first major German city to fall to the Allies and faced heavy bombardments, by air strikes and then by the incoming American land troops, throughout late 1943 and 1944. Aachen reportedly anticipated the possibility of their cathedral being damaged in bombing and so transferred all its movable treasure to less conspicuous locations. In light of all this, the images of Aachen Cathedral actually seem remarkable for how intact the church is.

A black and white photograph mounted on card. Excerpt from caption: “AACHEN FALLS TO AMERICAN TROOPS. U.S. troops examine the main altar and the wreckage inside Aachen Cathedral. The cathedral was damaged during the bitter fighting for the city, which fell to troops of the first U.S. Army on October 20, 1944, seven days after expiration of a “surrender or die” ultimatum.” [CON_B09767_F001_019 – GERMANY, Aachen. “Aachen falls to American troops”. Attribution: Keystone Photo 484403. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

The bomb that damaged these windows was reported to have fallen through the church roof on Christmas Eve, 1943 and to have then rolled out onto the street where it finally detonated, blowing in the windows.

The cathedral was first commissioned by Charlamagne in around 796 and then was added to in 1355. This addition was in the form of a Gothic choir, the focal point of which was the magnificent stained-glass windows. These 14th Century windows were not the same ones which were destroyed in the bombing. They had in fact been shattered already by a hailstorm in 1729; those in the cathedral in 1944 were a neo-Gothic replacement.

In photos taken before the war, the windows can be seen to have detailed figural designs at the bottom, but with a much simpler geometric pattern in the rest of the space. This is quite strikingly different from the modern iteration of the windows, designed post-war by Walter Benner, Anton Welding and Wilhelm Buschulte, which have a far greater number of figural compositions as well as more intricate geometric design.

A black and white photograph mounted on card, depicting the untouched interior of the choir of Aachen Cathedral. [CON_B2200_F002_002 – GERMANY, Aachen. Aachen Cathedral. Int: choir looking NE. Taken before the windows were bomb-damaged. Attribution: Photo Marburg 64678. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC]

[Image to follow]

A colour, digital photograph of the interior of the choir of the Aachen Cathedral. Large, multicoloured stained glass windows wrap around the curved side of the choir and the wall to the right of the photograph. The glass is coloured mainly in vibrant blues, reds, pinks, and purples. The interior is well lit with electric lights hanging from the vaulting, visible on the ceiling. To the left of the photograph, a painted wooden sculpture of three angels or cherubs is visible. In the centre of the choir there is a hanging sculpture decorated with gold leaf. The walls of the interior are richly decorated, though it is unclear if they are painted or tiled.

[GERMANY, Aachen. Aachen Cathedral Choir. Taken after the new, post-war windows were installed. Attribution, alamy.com. DWP911]

It is obvious why the windows were not left in their damaged state, which would have left the cathedral completely vulnerable to the elements, but perhaps surprising is that they chose to reinvent the windows rather than recreate the old ones. Part of this is probably, like with the other two pieces discussed, a question of age. As mentioned, the windows damaged by the bombs were not the originals and as such would have held less importance to the city’s historical fabric than they would have done had they stood there since the 14th Century. Also of possible relevance is the appearance of the windows themselves. The original design was very sober in comparison to the modern one and it is not inconceivable that those in charge of arranging the cathedral’s repairs would have seen the damage as a blank slate from which the cathedral’s appearance could be altered.

Unlike in the cases of Wells Cathedral or of Andromeda, the windows of Aachen had the dual factors of being irreparably damaged and a crucial structural part of the building. The combination of these two meant that it was imperative that the windows were remade, but that they could be made potentially in any style because the historic craftsmanship which may have been otherwise preserved was destroyed.

If the three examples used are looked at as a group, then it seems clear that there are no set protocols for dealing with damaged art and while some is seen as worthy of preservation, other works are discarded. It is understandable why artwork that is damaged is sometimes destroyed or abandoned, Aachen Cathedral could not function with broken windows and the place which had displayed Andromeda had ceased to exist. However, this does not mean that the damaged pieces are worthless or that they should be forgotten. Here is where photography can become so useful as a medium. Even if damaged objects or buildings cannot be kept in their state forever, photographs can capture them in this vulnerability beyond the time in which they have been repaired, replaced or further degraded.

Caitlin Campbell

Courtauld Connects Digitisation

Oxford University Micro-Internship

Participant