Finding Humanity in Architectural Images of Amdavad

This blog post is designed as a virtual exhibition and is best viewed here. An accessible version is available below.

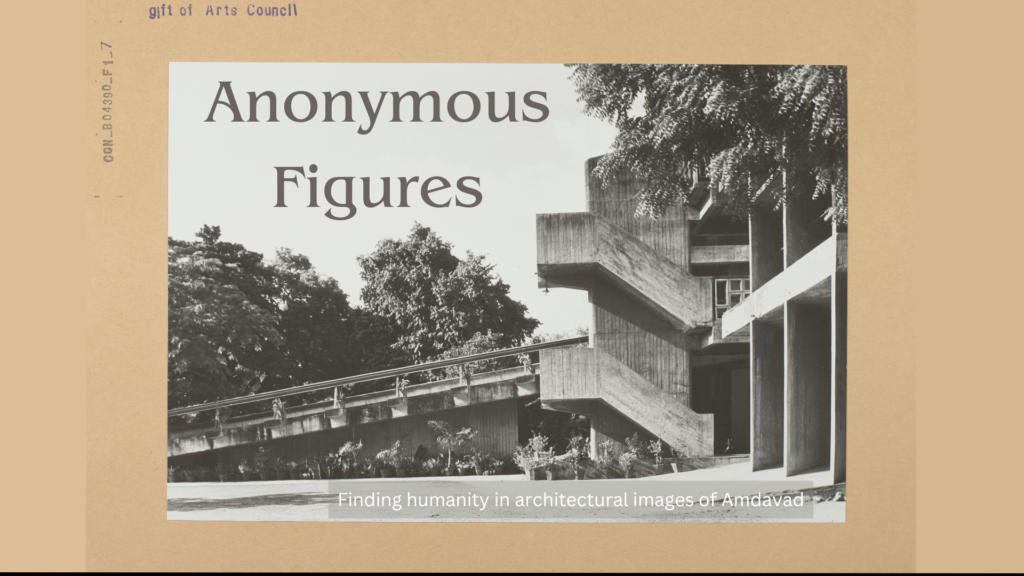

In the 1950s, the Franco-Swiss architect Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, known as Le Corbusier, designed and oversaw the construction of four buildings in the city of Ahmedabad, Gujarat. Architectural photographs of his work are the only trace of twentieth century Ahmedabad in the Conway Library. Such photographs are cold and impersonal: detached, reverent images capture the triumph of the architect. Le Corbusier had a vision for modern Indian architecture and the photographers honour and exalt his work.

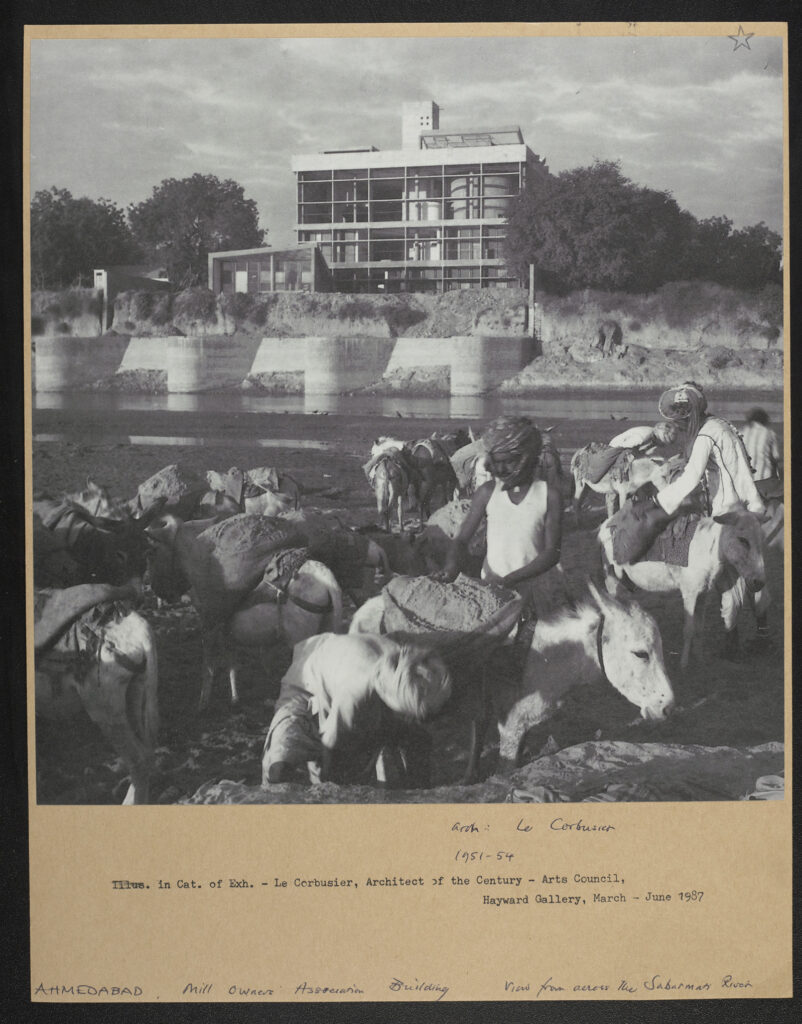

In the Conway Library, photographs are skewed towards Europe. Photographs of the ‘East’ suffer from the colonial gaze of the white photographer, and those taken in Ahmedabad are taken in celebration of a European architect. The attribution on the photographs is always to the architect, Le Corbusier, though some of them name the photographer too. English words are used to locate the image: ‘Ahmedabad’ rather than the Gujarati, ‘Amdavad’. ‘Museum’ rather than its name, Sanskar Kendra. ‘Le Corbusier and assistants,’ even though one ‘assistant’ is the famous Indian architect Balkrishna V Doshi.

Sometimes, anonymous figures find their way into architectural photographs. A man hidden at the back of the frame, a woman at work. We don’t know who they are, or the stories they would tell.

CON_B04390_F001_005

CON_B04390_F001_005

How do you tell the story of someone that you do not know?

Saidiya Hartman narrates the stories of the nameless and voiceless, those whose lives are impossible to trace due to their absence from historical archives. She uses a method of ‘critical fabulation’ and speculation which draws inferences from documents and photographs to craft a written portrait of her historical subject.

In what follows, four photographs guide the text. Each photo is accompanied by three captions in which I attempt to disrupt the colonial gaze and bring to life the strangers caught in these images. In the first caption, I use my imagination to speculate on the people pictured and the events that were unfolding as these photos were taken, in a method similar to Hartman’s. A second caption is crafted from my interpretation of the photograph and research into the social context the building. The final caption follows the format of the architectural photograph: an impersonal account of the building.

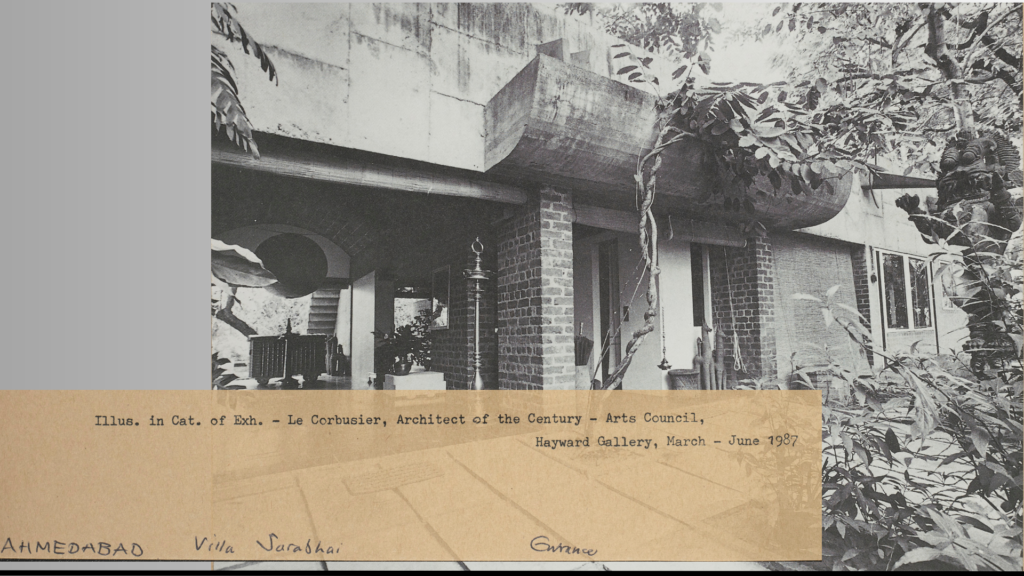

CON_B04390_F001_016

CON_B04390_F001_016

Early morning. The sun had just begun to cast a bright light onto the Sanskar Kendra, but under the shade of the building it was still cool and quiet. A few voices drifted across the open air from across the museum, broken only by the whoosh of the jhadu against the concrete slabs. The woman had noticed the European photographer out of the corner of her eye, standing on the ramp and looking down over where she was working. She didn’t pay him much notice, continuing her sweeping without a second thought.

Sanskar Kendra City Museum, viewed from ramp

Lennart Olson, the Swedish photographer, took this picture from the entrance ramp to the City Museum of Ahmedabad. The woman in the image shows the scale of the building: the pilotis hold the building above the ground, forming a shaded, open courtyard. Light and shadow play in this photograph.

Overexposure due to bright sunlight burns the columns at the back and the woman’s figure is cast as a sharp silhouette. On the floor above, sunlight flows through the back window, illuminating the tiled floor and exposed brick walls of the interior.

Ahmedabad City Museum, Le Corbusier, 1954.

The Sanskar Kendra Museum in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, was designed by the great twentieth- century architect, Le Corbusier. Its foundation stone was laid in 1954. The museum is elevated 3.4 metres above ground level, supported by pilotis. Le Corbusier designed the building to protect from the heat, with 45 large basins built into the roof as a cooling mechanism. Today, the museum is closed and parts of it have begun to fall down.

Intermission

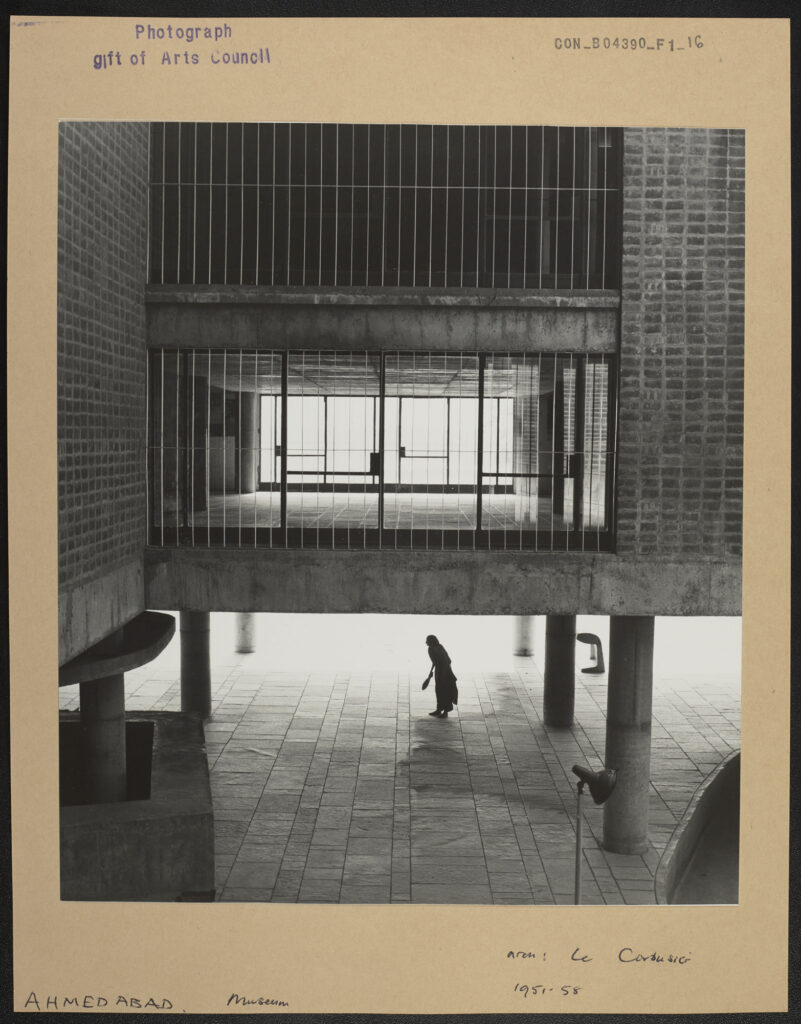

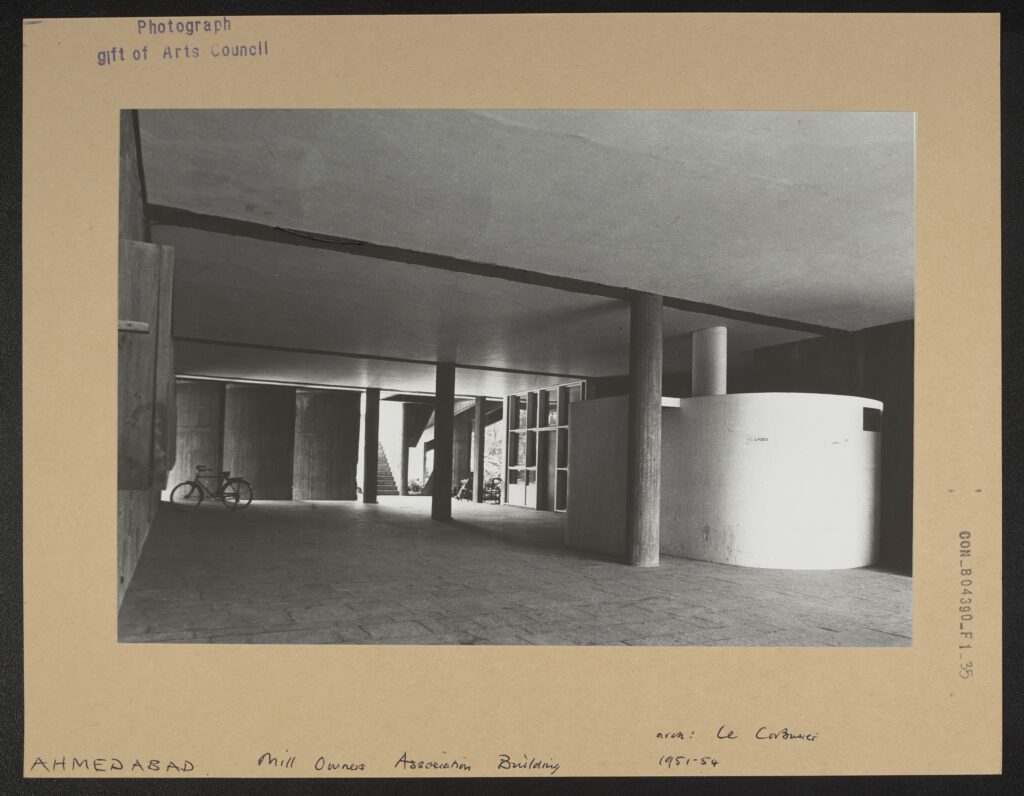

CON_B04390_F001_035

CON_B04390_F001_035

Within a forest of cool concrete, a man reclines in the warmth of the afternoon. He sits, partially shaded from the sun, under a narrow column. Crossing one ankle over the other he stretches his legs out into the sunlight and opens his book. This is well-earned period of respite from working and, hopefully, nobody will disturb him. As he reads, the plants and the trees next to him rustle and dance in the warm breeze.

Ground floor of the Mill Owner’s Association Building

This photograph depicts the ground level of the Mill Owner’s Association Building. The name and address of Snehal Shah are recorded on the back of the image, though it isn’t clear whether Shah is the photographer, the collector, or somebody else. Two paper signs posted on the wall on the right of the image, a bike parked on the left, and a man reclining in a chair at the back of the scene indicate that the building was in use, and that the photo was taken sometime after it was completed in 1954.

Mill Owners Association Building, Le Corbusier, 1954

The Mill Owner’s Association Building was commissioned by the association’s president, Surottam Hutheesing. The building, which represents Le Corbusier’s vision for modern Indian architecture, was the first of four by the architect to be completed in Ahmedabad. Large brises-soleil protect the interior of the building from the sun, whilst allowing for a breeze to enter from the Sabarmati River below, and creating a sharp, geometric pattern in the concrete.

Posture

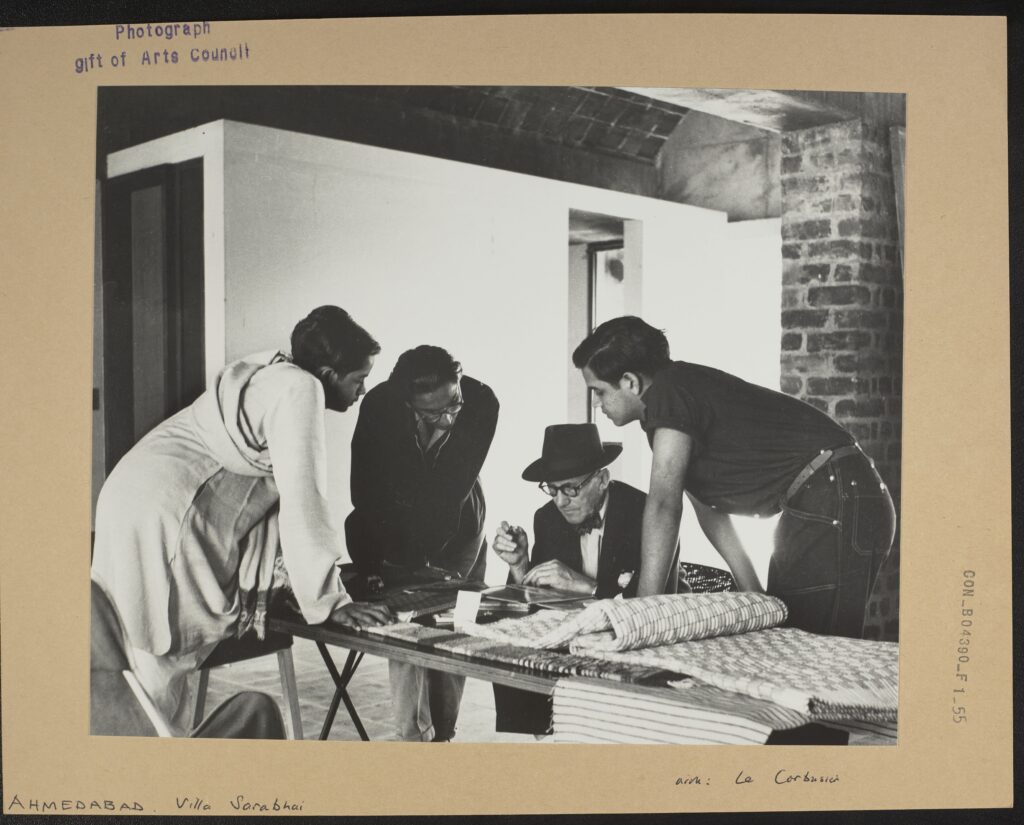

CON_B04390_F001_055

CON_B04390_F001_055

The European architect dominated the room. He sat at the table, posing for the camera almost comically with his pen. The other young men gathered around him as if to absorb his knowledge and acknowledge his wisdom. He was certainly a character: he never seemed to remove that hat, and they had overheard his needlessly callous response to Madame Sarabhai when she requested that he place railings on her balconies to prevent anyone falling from a height.

Le Corbusier and ‘assistants’ at Villa Sarabhai

In this posed photograph, Le Corbusier is surrounded by two unnamed men and the Indian architect, Balkrishna V Doshi, who wears a black coat. Power is demonstrated in no uncertain terms. Sitting at the centre, wearing his characteristic thick-framed glasses, Le Corbusier commands the image. Leaning over him, the other men demonstrate who is in charge. Doshi stands next to him, lower in status but easily able to see and participate. The other two men must lean over much further, as if in submission.

Villa Sarabhai, Le Corbusier, 1955

Villa Sarabhai was commissioned by Manorama Sarabhai, the sister of Chinubhai Chimanlal, a millowner and first mayor of the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation. The house was completed in 1955, having been constructed with a combination of brick and concrete. A large exterior staircase and slide extend from the pool at ground level to the first-floor terrace.

Cubic garden in Amdavad

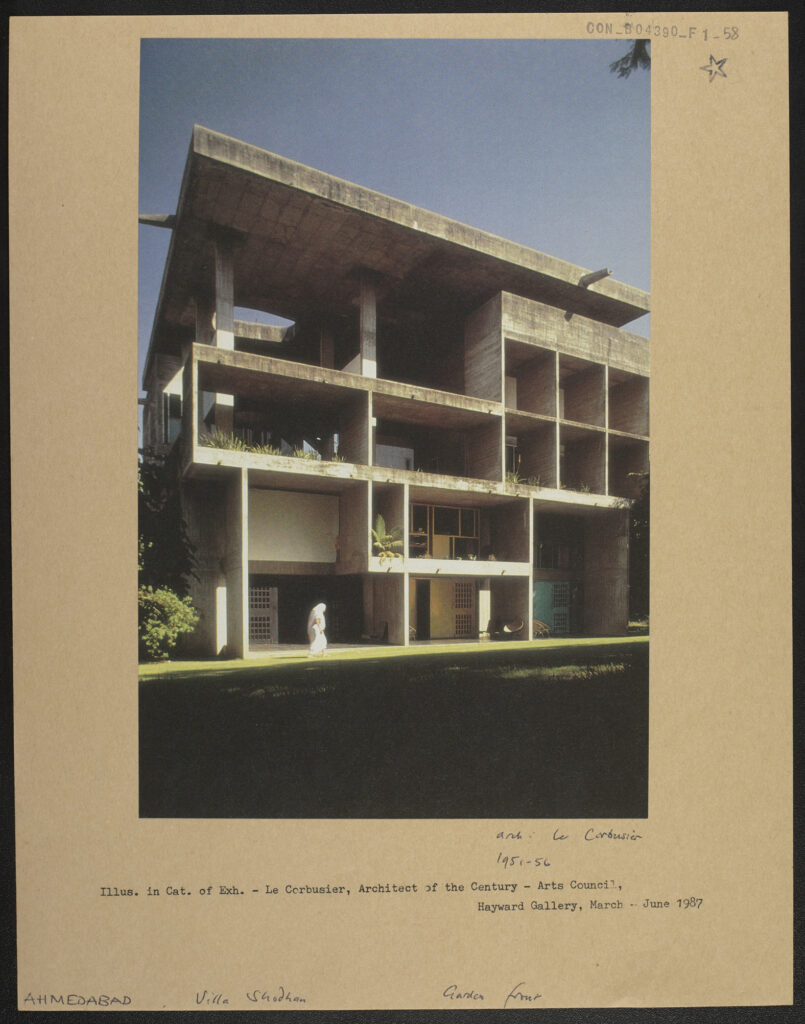

CON_B04390_F001_058

A woman crosses the garden in front of the house. I am unsure of who she is: could she be a relative of Shyamu Shodhan? His mother perhaps? The house towers above her, enormous. Its straight lines and right angles bluntly carve the clear sky. It is a symbol of wealth and status and she isn’t unaware of this fact. She walks along the length of the house in a narrow strip of sunlight, which glances off her white saree. The sun has long passed its peak and the evening air has begun to cool, yet the grass beneath her bare feet is still warm as she walks.

Front of Villa Shodhan

This photograph is captioned ‘Garden front,’ but is not attributed to any photographer. A woman is pictured walking across the garden at Villa Shodhan. The building is formed of concrete in geometric, rectangular lines. Chairs left out under the shade of the overhangs suggest that the front of the house may be used as a modernist veranda, a place for postcolonial rest.

Villa Shodhan, Le Corbusier, 1956

Completed in 1956, Villa Shodhan was initially commissioned by Surottam Hutheesing of the Mill Owners Association to showcase his social and economic position. However, the plans were eventually sold to Shyamubhai Shodhan, another millowner. The house combines elements of Indian architecture, such as the double-height entry hall, and elements typical of Le Corbusier, including an internal ramp that connects the floors.

CON_B04390_F001_057

References

Images (in order of appearance)

Ahmedabad, Mill Owners’ Association Building. Attribution: Snehal Shah, CON_B04390_F001_007. The Conway Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

Ahmedabad, Mill Owners Association Building, View from across the Sabarmati River: Illustration in Catalogue of Exhibition – Le Corbusier, Architect of the Century – Arts Council, Hayward Gallery, March – June 1987. Attribution: Lucien Hervé, CON_B04390_F001_005. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

Ahmedabad, Villa Sarabhai, Entrance. Illustration in catalogue of exhibition – Le Corbusier, Architect of the Century – Arts Council, Hayward Gallery, March – June 1987. No attribution, CON_B04390_F001_043. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

Ahmedabad, Museum. Attribution: Lennart Olson, CON_B04390_F001_016. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

Ahmedabad, Mill Owners Association Building. Attribution: Snehal Shah, CON_B04390_F001_035. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

Ahmedabad, Villa Sarabhai. No attribution, CON_B04390_F001_055. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

Ahmedabad, Villa Shodhan, Garden Front Illustration in Catalogue of Exhibitions – Le Corbusier, Architect of the Century – Arts Council, Hayward Gallery, March – June 1987. No attribution. CON_B04390_F001_058. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

Ahmedabad, Gujarat, Villa Shodhan. Attribution: Lennart Olson, Alinari Brothers Ltd, Edizioni Alinari. CON_B04390_F001_057. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC- BY-NC

Books and Articles

Architexturez. Sanskar Kendra City Museum. https://architexturez.net/doc/az-cf-178850 (Accessed 22 June 2023)

GreyScape. Capturing Modernist India. https://www.greyscape.com/capturing-modernist- india-with-john-gollings/ (Accessed 22 June 2023)

Hartman, Saidiya (2019). Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women and Queer Radicals. London: Serpents Tail

Hartman, Saidiya (2008). Venus in Two Acts. Small Axe 12/2: 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1215/-12-2-1

Jones, Rennie. AD Classics: Mill Owners’ Association Building / Le Corbusier. Arch Daily.

https://www.archdaily.com/464142/ad-classics-mill-owners-association-building-le-corbusier

(Accessed 22 June 2023)

Something Curated (2022). The Indian Architects Behind Le Corbusier’s Seminal Work In Chandigarh. https://somethingcurated.com/2022/04/19/the-indian-architects-behind-le- corbusiers-seminal-work-in-chandigarh/ (Accessed 20 June 2023)

Zinkin, Taya (2014). From the archive, 11 September 1965: An awkward interview with Le Corbusier. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/sep/11/le-corbusier-india- architecture-1965 (Accessed 22 June 2023)

Kasturi Pindar

Courtauld Connects Digitisation

Oxford University Micro-Internship

Participant

Twitter: @kastvri

Instagram: @kasturieats