Most residents of Bevin Court, Cruikshank Street, live in a state of oblivion in terms of the history of Vladimir Lenin’s time in Finsbury. This has led to a lack of understanding for many people to which they experience shock as well as newfound curiosity about Lenin’s significance, not only in London but also the USSR. Therefore, the following story draws evidence and inspiration from sources from the Conway Library and will have snippets of information throughout the piece in italics to help depict the mystery of the Lenin memorial and how exploring the unknown can lead to insightful understandings of history.

Resident 28 stood in a state of shock, tea in hand, steam rising from the mug as a detective named Bertie, accompanied by a policeman, stated the findings of a head buried under the stairwell of Bevin Court. Immediately, Resident 28 was unnerved by the discovery and, as soon as the detective and policeman took their leave, rushed to the neighbour at number 30 with the news. His eyes glinted with curiosity as much as the same shock as him. Resident number 30 was intrigued by the discovery of a head found under the stairwell. More so, he was eager to know more about anyone who had any information regarding the person that was found under the stairwell, was it another resident? Was there a psychopath living amongst them? Or was it simply a random episode that would leave a red mark over the collective housing estate? Thus, Resident number 30 started an online messageboard, with an attached photo and one message: “who’s under the stairs?”, to document his findings, for he wished to shed light on the ambiguous figure and the sudden attention the discovery had attracted.

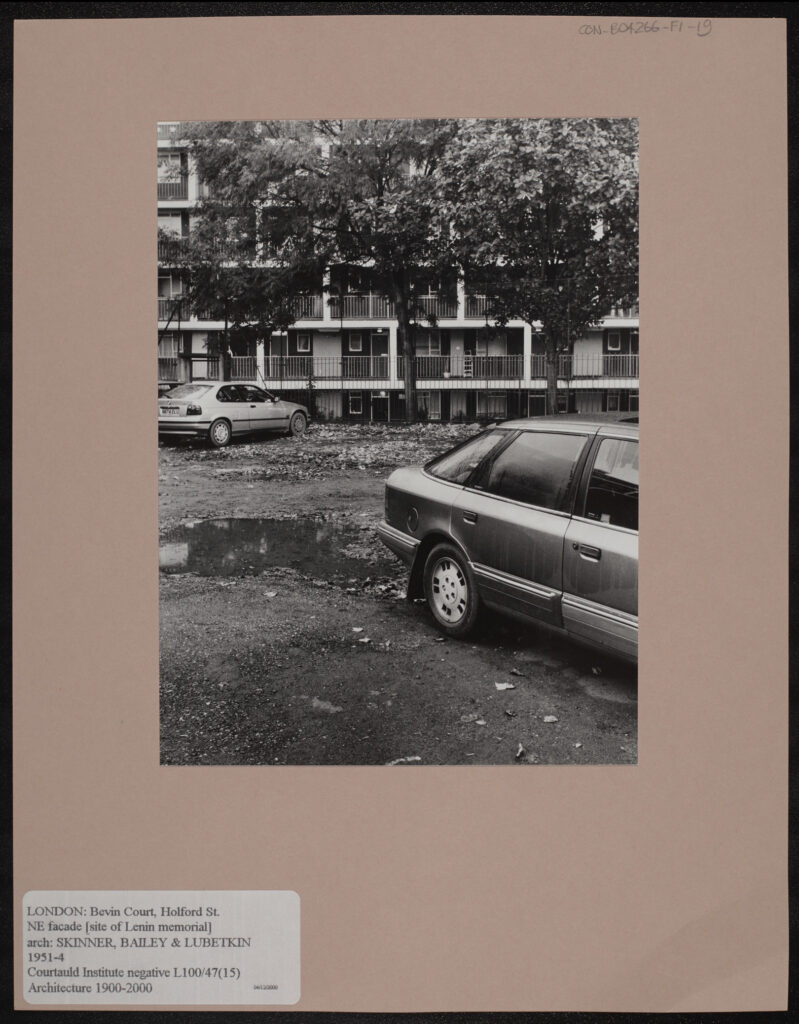

A black and white image of the façade of Bevin Court, there are rows of windows and balconies which are partially obscured by rows of trees. There is a light coloured car parked at the side of the building and another, darker car is parked in the foreground. The ground is wet and there is a large puddle behind the second car. [CON_B04266_F001_019 – LONDON: Bevin Court, Holford Street, northeast façade [site of Lenin memorial]. Architects: Skinner, Bailey, and Lubetkin, 1951-4. Courtauld Institute negative L100/47(15).]

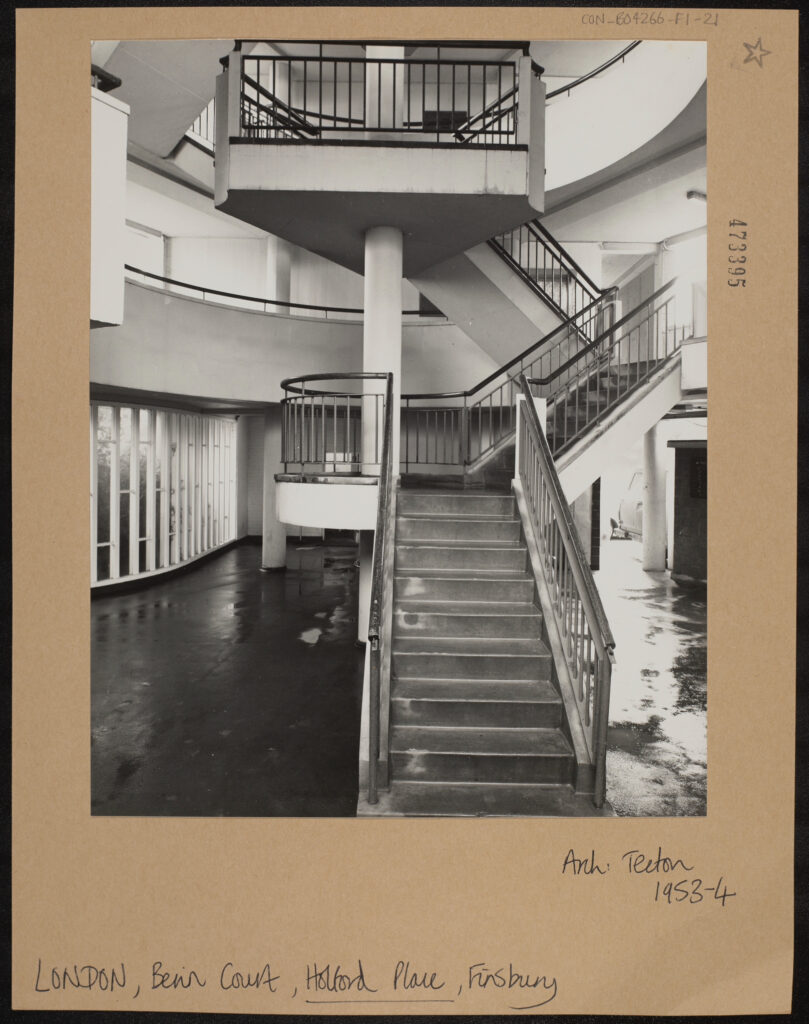

A black and white photo of the interior of Bevin Court, taken at the bottom of a short set of stairs. The ground is wet and made of a dark concrete. To the left of the image there is a curved window on the ground floor and the first floo balcony above that. The balcony stretches across the entire space. The second floor is visible at the top of the image. At the top centre of the photograph there is a stair platform overlooking the stairwell. [CON_B04266_F001_021 – LONDON, Bevin Court, Holford Place, Finsbury. Architects: Skinner, Bailey, Lubetkin, 1953-4.]

My idea for this story came from learning about the history of Lenin who had lived in 30 Holford Square with his wife in 1902-1903 to avoid persecution by the Tsarist regime. The actual building, however, suffered severe damage during World War II and could not be restored. As a result, with the permission from Finsbury Borough Council and with a push by Architect Berthold Lubetkin and the Foreign Office, a Lenin memorial was erected opposite the site. I thought that it would be great to include small pockets of information in the story thus, Resident 30 refers to the house number in which Lenin lived. While the detective is called Bertie as a reference to Berthold Lubetkin (the architect that designed Bevin Court). The reason I decided to make the characters anonymous is to add to the mystery itself and to create an atmosphere where the reader feels left in the dark searching for answers.

As Resident number 30 was unsure about the actual events of the discovery he sought to investigate all possible options. First, he decided to venture downstairs to the exact location where the head was found in the centre of the daunting square; his face as red as a communist’s fervour. Suddenly, he felt the need to know the history of Bevin Court to answer the questions of ‘What prompted the murder? Why the head? What is its significance?’ But, more so, he wanted to visibly see the head first-hand, he wanted to materialise the image in his head. ‘Was the person important? How did they die? Was it bloody? Was it disfigured? Did he want it to be?’ The thrill of discovery ignited a revolutionary flare within him. He posted another picture on messageboard with the caption: “Look what I uncovered! Find out who? – head found in Cruikshank Street”.

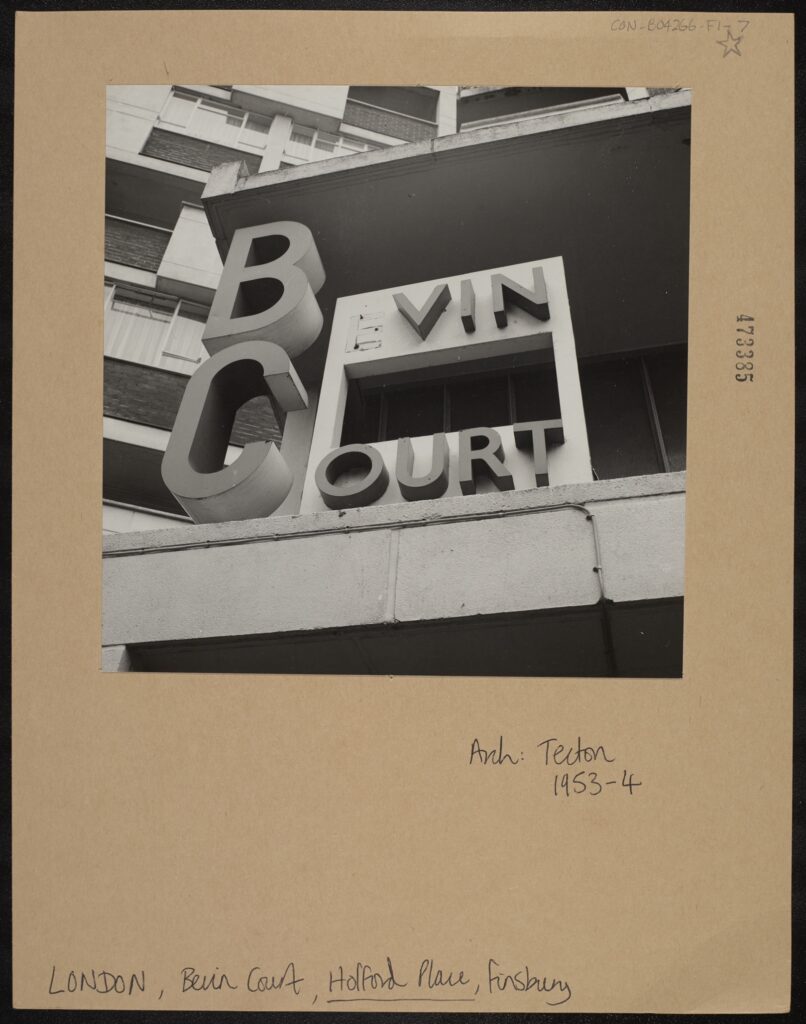

A black and white photograph depicting the Bevin Court entrance sign, with the façade of the building visible in the background. The sign reads “BEVIN COURT”, with the letters “B” and “C” significantly enlarged. The letter “E” is missing, with its outline faintly visible underneath. [CON_B04166_F001_007 – LONDON, Bevin Court, Holford Place, Finsbury. Architect: Skinner, Bailey, Lubetkin, 1953-4. Entrance sign.]

Still, Resident number 30 was underwhelmed. More had to be done. He could not fathom the unnerving power of each image he had found. The photos had awakened a feeling of need to know more beyond the border frames. Beyond the black and white.

The online messageboard sounded a notification. A reply. “Bevin”.

With that one-word, Resident number 30’s excitement grew. His heart beating like a drum, the same beat that has echoed out from the drum staircase for years. Banging to get out, to be discovered. Light cascaded down onto his notes from the window as he staggered to pile them into a folder. He fumbled with his camera. He had to go back downstairs. ‘Bevin.’ What does this mean? Bevin Court? How can a murder be so terrific and the chase to capture an image, a piece of evidence that holds many clues, so great? Never mind Detective Bertie, for Resident 30 wanted to continue his own hunt for the truth, in the meantime he took a snapshot of his view outside as he made his way towards the bottom of the stairwell.

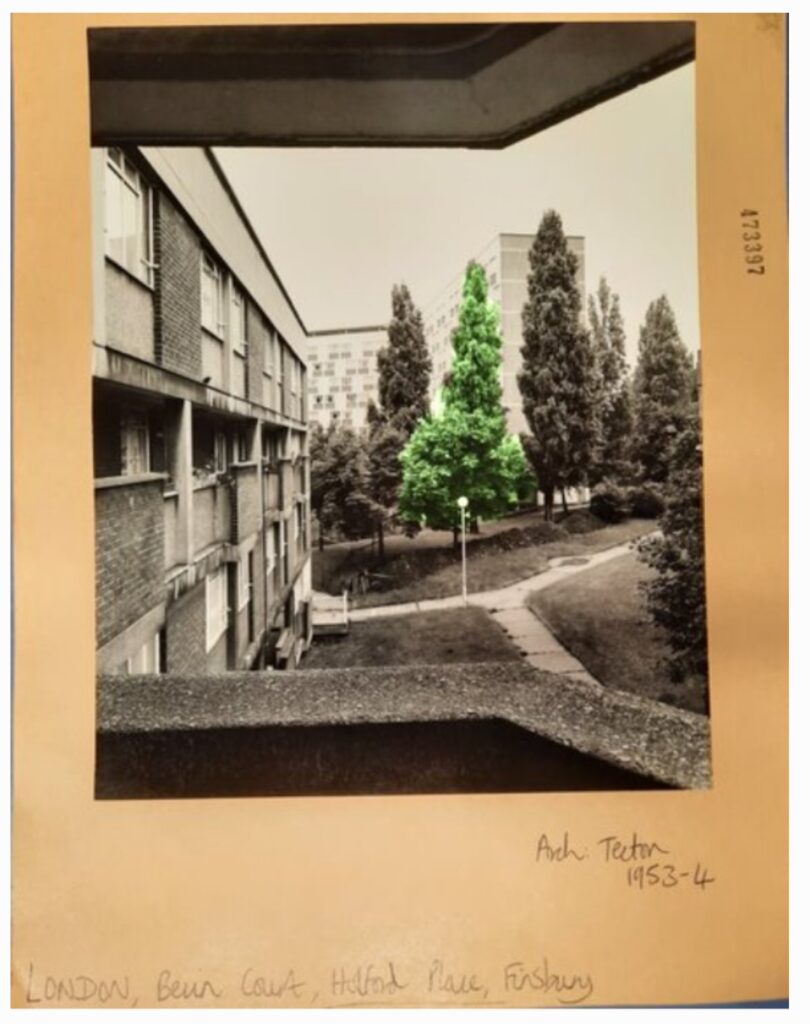

An edited image of the exterior of Bevin Court, taken from one of the building’s balconies. The photograph is framed by the walls of the balcony and the floor of another balcony above. To the left, another exterior wall stretches away from the foreground. There is a split path in the centre of the photograph with a street lamp and several large trees. One tree in the centre has been coloured a vibrant green. [CON_B04266_F001_001 – LONDON, Bevin Court, Holford Place, Finsbury. Architect: Skinner, Bailey, Lubetkin, 1953-4. Colourised using LightxEditor. Original image is linked.]

At first glance he noticed nothing unusual about the photo he had taken, but on closer inspection he saw a splash of colour bleed onto the page. His image was coming alive just like his imagination and more so as he was coming closer to the clues. Bevin Court. He had to do some research. What was the history of Bevin Court? He scarcely knew much. A simple Google search would suffice as to who Bevin was, but he craved more. Heading to the Courtauld Library to look at the collections, he knew answers were yet to be revealed; the crisp images waiting to burn under his scrutinising gaze. He travelled down into the library and picked up a red box full of dust and knowledge. He began to furiously browse the web to attain his desired end. Bevin Court:

The area around Bevin Court was owned by the New River Company who leased the land as pasture and in 1841-48 a formal square was laid out and named Holford Square. It was named after the governor of the New River Company, Charles Holford. After destruction from World War II bombing, Holford Square was redesigned by Berthold Lubetkin after Finsbury Borough Council bought the site with the idea to retain the shape of the square. Lubetkin placed a block of flats in the centre of the old square. Three branches of flats radiated from a drum staircase (which I used as a metaphor in the story to describe the cylindrical shape of the stairs and the beating of the protagonist’s heart). This layout leaves no flat with a north only aspect. Bevin Court was not always named what it currently is. In fact, it was supposed to be Lenin Court, but after vandalism of the memorial and uproar by the residents it was named after Ernest Bevin, Minister of Labour (1881-1951). Throughout the story I refer to the shape and architectural features of Bevin Court throughout the story to immerse the reader and give them a sense of physically being present at the murder location themselves.

The information was a cacophony of words, a divine hell that only led him into a madness of wanting more but one word continuously appeared among the research: ‘Lenin’. Lenin, along with a picture of a stone face, somber and grey with a red hue. Colour was becoming the definition of discovery. The images were the revolutionary beginnings of his own human imagination and comprehension. ‘Lenin was a Russian revolutionary politician who served as the founding head of the government of the Soviet Union from 1917 to 1924 and of the Soviet Union from 1922 to 1924’. Still, Resident 30 was befuddled. Murder. Head. Lenin. Red. Furthermore, he was bewildered as to the explanation of the bright colours for it seemed to heavily contrast the dismal mystery. Perhaps it was the way the light hit the photo that affected its outcome. Perhaps the colour reflected his mind oozing with newfound knowledge onto the page.

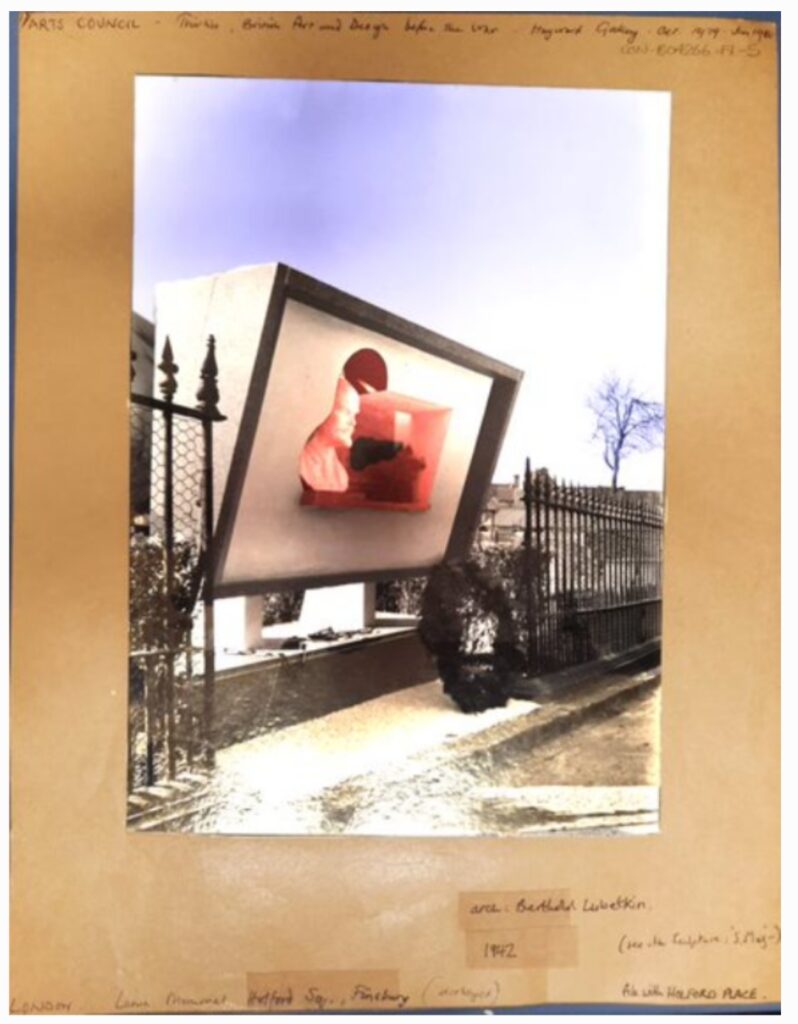

A colour photograph of the Lenin memorial with a bust of Lenin enclosed within a glass and stone container. Accompanying the bust is a plaque, the writing obscured, and a vase containing a bunch of dried roses. The container stands on a stone platform with chains underneath, with a wrought iron fence running along both sides of it. The sky has been recoloured in a sporadic, soft blue, and the interior of the memorial a brilliant red. [CON_B04266_F001_005 – LONDON. Lenin Memorial, Holford Square, Finsbury (destroyed). Architect: Berthold Lubetkin, 1942. Colourised using LightxEditor. Original image is linked.]

Unexpectedly, everything poured into his brain at once and aligned themselves like the socialist’s heart and mind. Imitation murder perhaps? He rushed to Detective Bertie with the news, lungs full of anticipation and exasperation at being so close yet so far. Bertie peered upon him with disbelief, he found the information insightful but Resident 30’s passion? Intense and deranged. Surely a single murder could not have wrangled the resident’s brain in such a way. His excitement seemed to exceed the red fear and repulsion conjured by the revelation of the head found under the stairwell. For the detective’s own eyes could not see the colour on the images and understand what Resident 30 had unearthed.

Here, I took inspiration from a project by Phil Dimes called “Chasing Kersting” where he would take interest in a particular photo and travel to the location to take a present-day image himself. He would then recolour the image in a unique way. I sought to do a similar thing by gradually recolouring the images from the Conway collection as the story progresses and as the protagonist solves the murder mystery. At the end, he is surprised to find the image almost most completely coloured, bright and modern (by using a present-day photograph at the very end) which represents his own complete knowledge and the inspiration it has drawn from him.

Detective Bertie turned to Resident 30 and advised him wisely: “’Architecture can be a potent weapon… a committed driving force on the side of enlightenment’, as Lubetkin famously said himself, ‘do not fall into disillusion from uncovering nothing but a head and your own wild imagination. Leave this to empirical evidence”.

Resident 30 returned home. He was furious, he hated being undermined. He turned to the online messageboard and posted one last image of the stairwell looking upwards, clinging onto hope. The stair platforms were like thin bridges between reality and illusion. He imagined his own head, heavy and decapitated with a look of depravity and despair, lips shrivelled and sagging at the sides, eyes black, gorged and bloody. He wrote in one sentence: “Stone head – head under the stairs”. He had an inkling of truth but was still in the dark. He waited to see if the anonymous person replied on the messageboard. Meanwhile, other residents were still convinced the head found under the stairs was a crazed moment of madness, a berserk person who slaughtered another innocent one. Nonetheless, Resident 30 felt that there was still a missing link between the chains that were loose around his mind, like that of the photo he found in the Courtauld with the ‘so-called’ Lenin bust and the huge chains slithering below him.

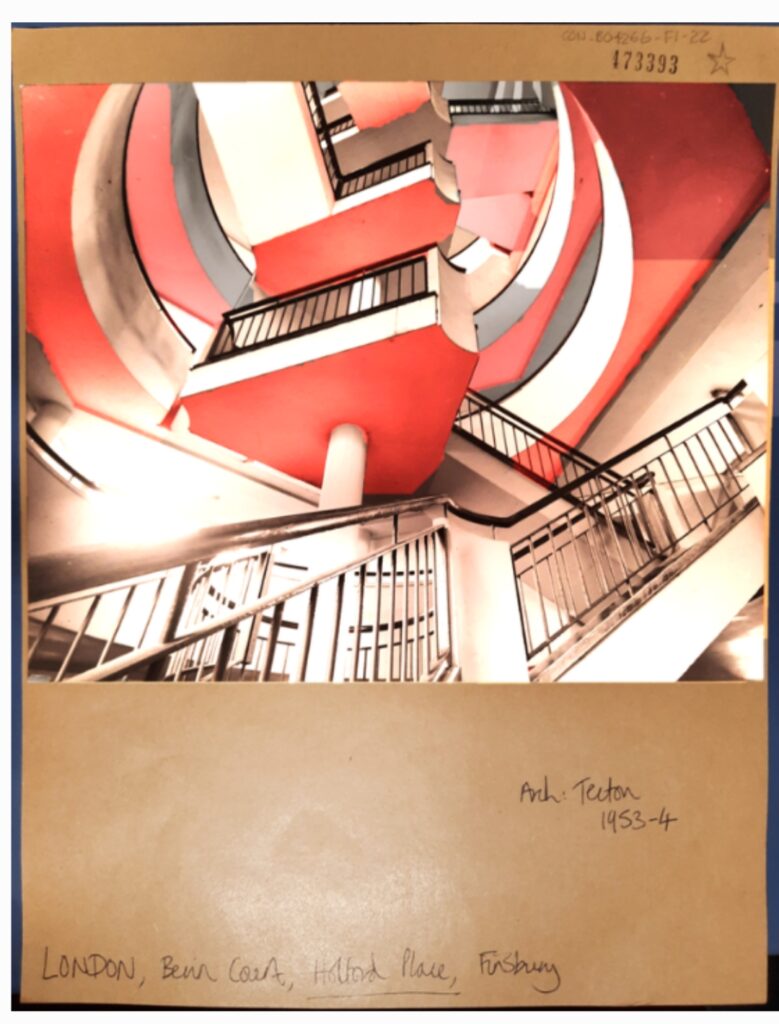

An edited image of the interior staircase of Bevin Court. The camera is angled up the hollow space in the centre, the top floor is not visible. The floors, walls, and railing curve around the staircase. The ceilings and floors of the upper levels have been recoloured a vivid red, contrasting with the white walls interspersed between them. [CON_B04266_F001_022 – LONDON, Bevin Court, Holford Place, Finsbury. Architect: Skinner, Bailey, Lubetkin, 1953-4. Colourised using LightxEditor. Original image is linked.]

Waiting for a reply sickened Resident 30 as he felt like he had a brick in the pit of his stomach. Worry grated on his mind like cement against cement. The walls were starting to close in as a reply finally came with the message “Lenin was under the stairs” and three coloured images attached. He never knew who the commenter replying was. That was a mystery. Sometimes it felt as if the reply was his own mind speaking to him through the images, communicating through the lens and reassuring him with a flash of hope. Lenin was under the stairs. Lenin was under the stairs. Lenin was under the stairs. He hastily hopped out of his chair. Out the front door. Down the stairs. The hallway became darker and darker as he stumbled closer to the bottom. He began to choke on black smog which filled the hall like clouds on an old negative image. The putrid smell of blood was permanently inked into his mind as he ran past the bottom of the stairwell. He needed to see Detective Bertie again. He was terrified and could not understand what was unfolding. His mind kept replaying images of under the stairwell of Bevin Court; he marvelled at the possibility that a small catacomb could exist beneath the ground. A catacomb with yellow brown tones tinting the damp cold walls and the smell of decay permeating the air. Yet he felt doubt gnaw at his skin, had his imagination run out of bounds.

The following photographs were taken at the present-day site by the author.

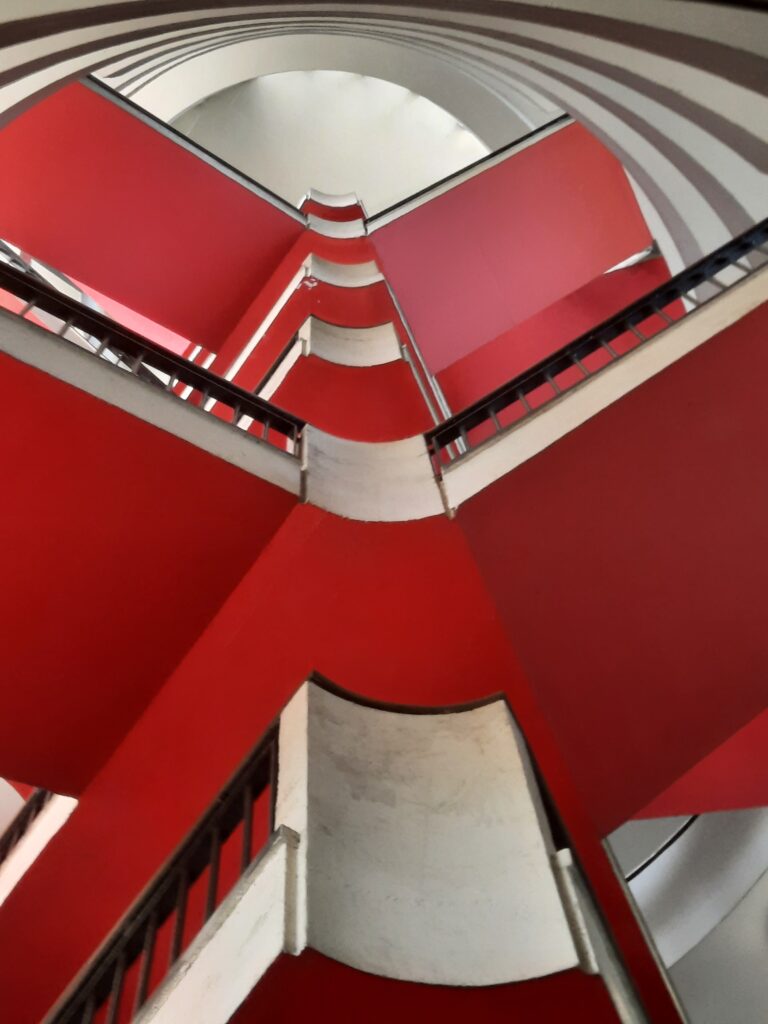

A colour photograph taken looking up to the ceiling in the central staircase inside Bevin Court. The walls curve around a red column, and the walls are painted alternately in a bright crimson and off white. The ceiling is visible towards the top of the photograph with the curved walls spiralling upwards. [LONDON: Bevin Court. Photographer: Lottie Alayo, 2023]

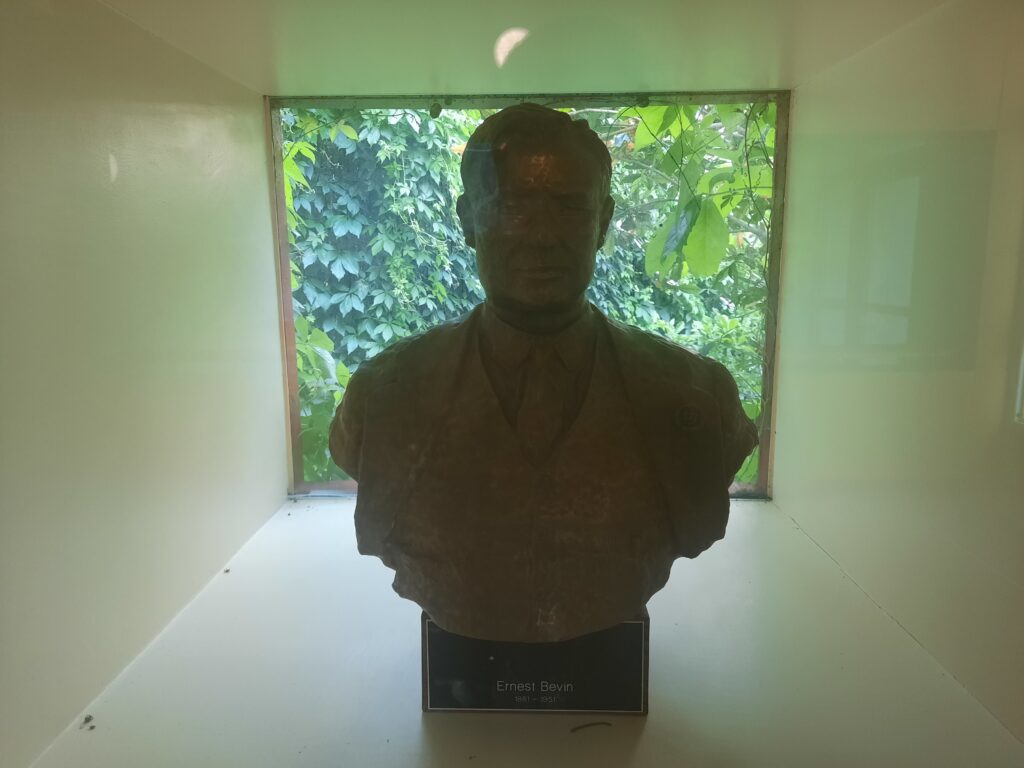

A colour photograph of the bust of architect Ernest Bevin. The bust is bronze and is visible in a white recess in a wall behind a pane of glass. Behind the bust, there is a window overlooking leaves and trees. [LONDON: Bevin Court. Photographer: Lottie Alayo, 2023]

A colour photograph of the exterior entrance to Bevin Court. The entranceway and sign are visible in the foreground, the walls made of white stone with brown brick details. The façade in the background is decorated similarly. Two separate walls, each covered in rows of windows, meet in the middle with a third wall housing a connecting walkway. At the centre of the top of the photograph, the clear sky is visible. [LONDON: Bevin Court. Photographer: Lottie Alayo, 2023]

Detective Bertie held his lips in a thin line, the ceiling fan buzzing annoyingly like a fruit fly. He turned to Resident 30 and looked upon him with bemusement while the latter stared in shock at the photos on the table. The head was, in fact, Lenin’s very own. The detective somehow had all the images he had spent hours gathering. Lenin’s head memorial, the stairwell, the outer façade of the flats, including the ones that he had received on the messageboard which were vibrant in colour, refined, modern, real and complete, like of a piece of artwork. A new head made of bronze was now mocking him. Ernest Bevin. How had he not noticed that before? Countless times he had glided past that same spot when leaving Bevin Court and never noticed the head’s eyes peek out at him from the glass pane. Was he always this oblivious about the place around him? Another picture showed the police resurrecting Lenin’s head from its resting place underground. What about the murder? There was none. But everyone saw it, the police were there? They were only unveiling the head, like a time capsule, as the bust itself was to be placed in Islington Museum for safekeeping. Rumours travel far and murder was the subject. His thirst for knowledge, information and truth was shrouded with a red blanket of imagination politics as he finally discovered Lenin’s political past, and it was littered with red folders of untold stories in the form of photographs. The murder was never real, but the history, effort and excitement were. Lenin was discovered and the mind was opened.

To finish, Lenin’s bust is now resting in Islington Museum, though it spent quite some time under Bevin Court and then some time locked away in the mayor’s office in Islington. Therefore, this story is sort of set in a parallel world where it is present day but some aspects of the story are of the past (as if Lenin’s head was just uncovered!). I decided to include a lot of colour imagery and metaphors of red in my work. This is because red is the symbolic colour of Communism, it was a revolutionary colour. Therefore, by using red to highlight graphic details of the murder as well as gently nudge at the idea of USSR Communism, I was able to easily draw many parallels. The reason I thought this story was fascinating was because it involved a significant, historical figure who had become a controversial topic because of his politics. Lenin is known by many world-wide and yet few know of his shenanigans in London, so I wanted to explore further. I also incorporated as much information not only in the form of small paragraphs but also within the story itself and many of the descriptive elements are drawn from the facts, pictures and the Courtauld. For example, where I mention ‘red folders’ or ‘fruit fly’ (for some humour) is referring to my time at the Courtauld. This is to add a more personal experience to the writing and to immerse the reader in the short story. My overall idea was to create a story that emphasises the importance of the Courtauld for discovery, individuality and creativity, and how images can change the perceptions and understandings of the world around us.

The end.

Lottie Alayo

Courtauld Connects Digitisation

Queen Mary University of London

Internship Participant