Maxime Durocher

The Gök Medrese was built in 671/1271 but, unlike the Buruciye and the Çifte Minare medreses, it is located at the foot of the upper citadel. Like other medreses in medieval Anatolia, its name (Gök meaning ‘Sky blue’) refers to the tile decoration of the building. The patron was Sāḥib ‘Atā Fakhr al-Dīn ‘Alī (d. 685/1285), a powerful Seljuk vizier during the first decades of Ilkhanid rule over Anatolia. He is known for his prolific architectural patronage, mostly in Konya and Kayseri, and his name is mentioned in different inscriptions throughout the building. It is interesting to note that he mentions the Seljuk sultan Ghiyāth al-Dīn Kaykhusraw III in the inscription located on the portal (RCEA 4640), but omits such a reference to his suzerain in another one located inside the courtyard (RCEA 4641).

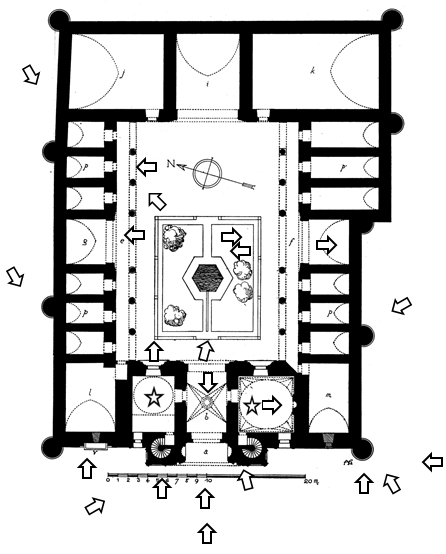

Despite important restorations during the 19th century (one is dated to 1239/1923-4 by an inscription) and the 20th century, the façade of the medrese and a large part of its architecture and decoration are still preserved. Constructed in limestone and brick, it is a typical 4-īwān structure organised around an open courtyard. The main īwān has collapsed, however, and was replaced by a wall constructed with rubble from the monument at an unknown date. The entrance īwān is covered with a star vault and flanked by two domed chambers (the south one is a masjid i.e. a prayer hall recognisable with the presence of a mihrab), like at the Buruciye Medrese. Two porticos run along the north and the south sides of the courtyard and the lateral iwāns are flanked by three vaulted rooms on each side.

The portal, prominent on the western wall, dominates the façade of the building and has impressive carved decoration concentrated on its marble cladding. The frame of the door consists of alternating blocks of coloured marble with animal heads springing from scrolls carved on each end stone. Such a zodiacal iconography is a common feature of Seljuk portal decoration. Two niches flank the door and a muqarnas vault, contained in a four-centred archivolt, surmounts it. Four different rectangular frames surround the portal, each with different geometrical or vegetal carved motifs. The use of bichrome marble and several motifs, like the plastic high-relief leaves and thick mouldings on the side of the portal, recalls the decoration of the mosque-complex built by Sāḥib ‘Atā’ at Konya in 1258. The decoration of the angle buttresses, consisting of palmettes carved on the fine cut limestone, is very similar to the design on the buttresses of the Çifte Minare Medrese in the same town and to the sculpture carved on the Turumtay türbe in Amasya (1278).

Two brick minarets surmount the portal composition, a feature introduced from Iran where it survives from the 12th century onwards. It is noteworthy that the earliest example of twin minarets in Anatolia appears on the portal of the mosque-complex built by the same patron in Konya. Both minarets, with sections identical to the minaret of the İnce Minare Medrese, also built by Sāḥib ‘Atā‘ in Konya, are decorated with turquoise and black glazed bricks and tiles. However, the tile decoration is concentrated on the lateral īwāns with geometric interlacing patterns forming eight-pointed stars on the lunette and in the masjid flanking the entrance passageway. Here an inscription is designed in black on turquoise tiles at the bottom of the dome. The dome itself, like the triangles in the transitional zone, is decorated with turquoise and black glazed bricks.

Finally, a rare example of an architect’s signature, Kālūyān al-Qunawī, is carved on the Gök Medrese (RCEA 4646). The identification of this signature with other examples found on buildings commissioned by Sāḥib ‘Atā’ (his mosque and the İnce Minare Medrese in Konya, for instance) raises the question of the mobility of architects and craftsmen in medieval Anatolia and their link to their patrons. Nevertheless, the identification of the same architect in other signature inscriptions is difficult because of variation in the Arabic script.

Interactive Plan

Image Gallery

Bibliography

- Aslanapa, O. Turkish Art and Architecture (London, 1971), 133, figs. 50-2.

- Blessing, P. Rebuilding Anatolia after the Mongol Conquest, Islamic Architecture in the Lands of Rum, 1240-1330 (Farnham, 2014), 104-15, figs. 2.19-2.24.

- Gabriel, A. Monuments turcs d’Anatolie, Tome Deuxième, Amasya, Tokat, Sivas (Paris, 1934), 155-61, pls. LII-LIX.

- Kuran, A. Anadolu Medreseleri (Ankara, 1969), 92-6, figs. 237-243.

- Rogers, J.M. ‘The Çifte Minare Medrese at Ezurum and the Gök Medrese at Sivas: A Contribution to the History of Style in the Seljuk Architecture of 13th Century Turkey’, Anatolian Studies 15 (1965), 63-85.

- Wolper, E.S. ‘The politics of patronage: political change and the construction of dervish lodges in Sivas’, Muqarnas 12 (1995), 39-47.

Inscriptions

Arabic text and French translations can be found in RCEA (nos. 4640, 4641, 4645, 4646, 4647, 4648) and TEI (nos. 2282, 2283, 2281, 2284, 29992, 29993, 29994, 29995, 29996, 29997, 29998, 29999, 30000, 30001, 30245). English translations are given by Patricia Blessing in Blessing, P. Rebuilding Anatolia after the Mongol Conquest, Islamic Architecture in the Lands of Rum, 1240-1330 (Farnham, 2014)