Patricia Blessing

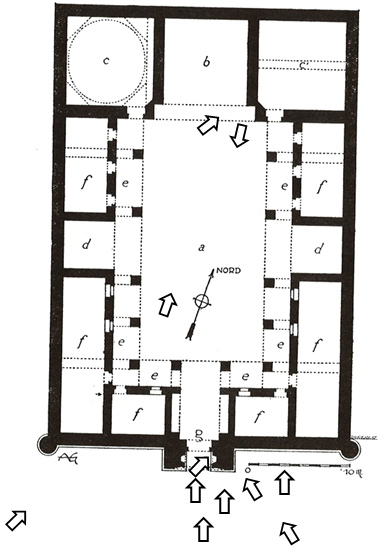

The Sahibiye Medrese, located in the centre of Kayseri close to the citadel, was founded by Ṣāḥib ‘Aṭā Fakhr al-Dīn Ali in 665/1267-8.[1] It has been suggested that the patron (or his architects) created a personal version of the style of Konya that was then spread to other locations in Anatolia, most notably to Sivas. In the Sahibiye Medrese in Kayseri, however, this transposition of a personal style based on the monuments of Konya did not take place. Rather than reflecting an imported style, this monument was modelled on other local monuments, most notably the Huand Hatun complex (634/1236-37), with its minimal carved decoration and exclusive use of stone for construction. Like many thirteenth-century madrasas, that is buildings intended for the training of scholars of Islamic law and theology, in Central Anatolia, the Sahibiye is built on a four-iwan plan with an open courtyard. Some of the lateral rooms are now closed off and used as stores. The portal, in the central axis, features a muqarnas niche above the doorway, surrounded by bands with geometric carving. Otherwise, little decoration has been preserved, on the façade or in the interior.

The foundation inscription is carved in two lines on a rectangular marble slab above the muqarnas niche. In addition to the foundation inscription a section of ḥadīth, referring to the importance of fiqh in the practice of Islam, appears just above the entrance to the monument.[2] Inscriptions from the Qur’an have not been preserved.

The decoration is a first hint at the persistence of local styles throughout the thirteenth century, in which some attempts at a stylistic unification were made, and their re-emergence immediately after the decline of the Seljuks’ central rule began following the Mongol conquest of Anatolia in 1243. The patron of the structure, Ṣāḥib ʿAṭā Fakhr al-Dīn ʿAlī, was a central figure during Mongol rule in Anatolia in the second half of the thirteenth century, from the 1250s until his death in 1285. He was one of several officials of the Seljūq court who managed to align themselves with the new overlords, and effectively ruled Anatolia by negotiating with the Mongols, on the one hand, and maintaining appearances for a largely powerless Seljūq sultan, on the other hand. This political shift entailed profound changes in patronage; Ṣāḥib ‘Aṭā Fakhr al-Dīn ‘Alī ‘s intervention in Konya is symptomatic of this transformation, while his patronage in Kayseri is less prominent.

Interactive Plan

Image Gallery

Bibliography

- Akok, M. ‘Kayseri’de Gevher Nesibe Sultan Darüşşifası ve Sahabiye Medresesi rölöve ve mimarisi’, Türk Arkeoloji Dergisi XVII.1 (1968), 133-184.

- Kuran, A. Anadolu medreseleri, vol. 1 (Ankara, 1969), 88-90.

- Şahin, S. ‘Sivas Gök Medrese (Sahibiye Medresesi) ve Kitabelerindeki Rivayetlerin Hadis Değeri’, Cumhuriyet Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi 10.1 (2006), 145-163.

[1] (1)amara bi-‘imrati hadhihi ‘l-madrasati ‘l-mubarakati fi ayyami ‘l-sultani ‘l-a‘zami shahanshah ‘l-mu’azzami Ghiyath ‘l-dunya wa-l-dini Abu ‘l-Fath Kaykhusraw bin Qilij Arslan (2) khallada ‘llahu mulkahu ‘l-‘abdu ‘l-raji ila rahmati ‘llahi ta‘ala ‘l-sahibu ‘Ali bni-l-Husayn ahsana ‘llahu ‘awaqibahu fÐ shuhuri sanati sitta wa sittina (wa)-sittam’ia. RCEA, No. 4595.

[2] “qāla ‘l-nabī ṣallī ‘llāh ‘alayhi wa sallam mā ‘inda ‘llāh […] wa mā afḍala min faqīh fī dīn wa li-faqīh wāḥid ashadd ‘alā ‘l-shayṭān min alf ‘ābid wa [?] shay’in ‘imād hadhā ‘l-dīn ‘l-fiqh [?]‘alayhi ‘l-s[…].” For a Turkish translation without reference to the source, see: Halil Edhem (Eldem). Kayseri Şehri – Selçuklu Tarihinden Bir Bölüm, ed. Kemal Göde, Ankara: Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı Yayınları, 1982, 120, n. 201. Part of the passage can be found in: Muḥammad ibn ‘Isā al-Tirmidhī, Sunan al-Tirmidhī, Vaduz: Jamʻīyat al-Maknaz al-Islāmī, 2000, kitāb al-‘ilm, bāb 19.