Nazenie Garibian

The elegant rotunda of Saint-Saviour in Ani is one of two churches with a central plan related to the Pahlavuni dynasty – the other one is St Gregory Abughamrents church.

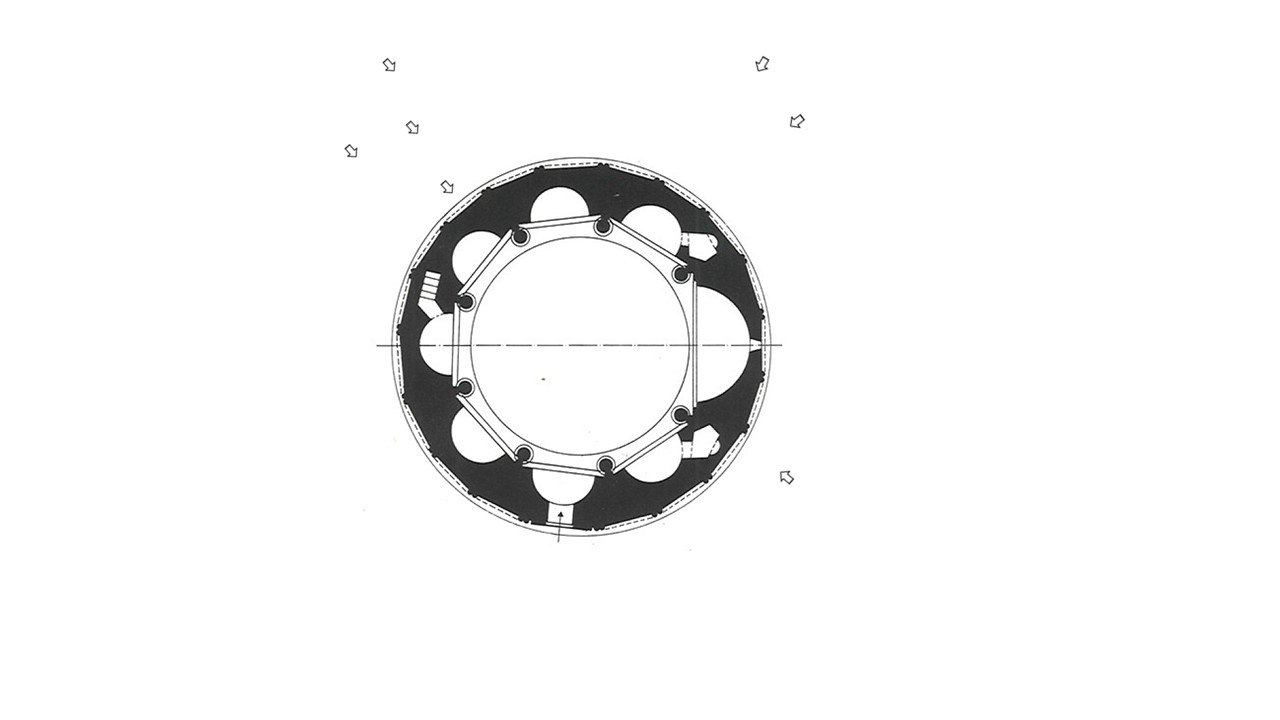

The two storey monument presents a polygonal shape at ground level with a unique design: the lower storey has nineteen sides externally and eight apses internally. These apses are separated from each other by dihedral pillars, into which the columns bearing the arches around the conches are inserted. The eastern conch, where the altar is located, is considerably larger than the others. Two tiny chapels are annexed to both its sides, opening off the flanking apses. The drum of the dome is separated from the nave by a bevelled cornice. It is a tall, round cylinder both outside and inside with twelve narrow windows. The huge central dome is semi-spherical. Its coif has disappeared.

The church hosts five inscriptions which allow us to reconstruct the history of the monument from its foundation. Thus, according to the main epigraph of 1036, the marzpan i.e. the governor Ablgharib (also known from the inscription of St Gregory Aboughamrents church) consecrated the shrine in the name of Surb Prkitch (St Saviour). His second inscription at St Saviour informs us that a year earlier, in 1035, he took an edict on behalf of King Smbat of Armenia to the newly crowned Emperor Michael at Constantinople. Obviously, the mission had been successful because Ablgharib came back with a piece of the True Cross that he had obtained ‘with great effort and great expense’. He then completed the sanctuary by erecting a ‘sign of light’ – probably a cross-stone (khatchkar) or a cross monument to house the precious relic.

The building was abandoned after the Seljuk conquest of Ani and fell into ruins. At the end of the 12th century, a priest named Trdat bought and restored the church with his wife Khoushoush, as recorded in the inscription of 1193. They also added winter and summer zhamatouns (narthexes). In 1191, during this restoration, a certain Mkhitar endowed the shrine with a bell-tower, which has now disappeared. The church was painted a century later (1291) by an Armenian artist called Sargis Parshikian. Finally, in 1342, atabek Vahram, the son of Ivane II Zakarian, had the dome restored by the architect Vasil; it seems that this greatly extended the size of the building. From this restoration resulted the nineteen sides and arcades of the ground floor that articulate and segment the periphery of the monument. Early in the 20th century a large crack appeared in the church, probably caused by an earthquake. During the expeditions of Nicolas Marr, some repairs were made in 1912. But this did not prevent half the building collapsing in the 1930s due to a strong earthquake.

The design of the church is supposedly attributed to Trdat, the famous architect of the time who built the cathedral at Ani, because of the name engraved at the top of the southern façade. Yet it seems to refer to the priest who did the restoration work.

The monument reveals an important characteristic of the architectural school of Ani: the intentional disjuncture between external volumetric configuration and the articulation of internal space. The external forms are far more compact than the interior ones.

Two arched windows open in the eastern and western sides of the building. The door is to the south with an oculus above it. Referring to the mighty rotunda of Saint-Gregory, built by King Gagik, as well as to the Saint-Gregory funeral chapel of the Pahlavuni dynasty, the church of St. Saviour also has arcades on two levels on its exterior. They rest on two slender semi-columns engaged by means of globular capitals. This type of capital is characteristic of 11th century Armenian art.

The difference between the two arcades is obvious: that of the drum is much more elegant and finely moulded with a lattice of wickerwork. The flat abacus of the arcades is sculpted with complicated curving strap-work, while the stringcourses of the capitals host carved animals intermittently. A frontally facing eagle decorates one of the arcades. That the arcade resulted from the restoration of 1342 can be seen in the ‘Seljuk chain’ and the frieze with angular weave on the top and bottom of the drum. The carved decoration on the interior comprises engaged columns, also crowned by globular capitals with a stringcourse abacus and bevelled edges over a swelling vase. On both sides, a cornice with the same outline and proportions separates the walls from the semi-domes in the conches.

The door has a heavy framework, rectangular and richly moulded; it is remarkable above all on account of the lintel with its deeply carved mouldings and the presence – unusual for this period – of a Greek frieze. This kind of portal is characteristic of the Ani school in the 11th century.

The layout of the mural paintings was documented before half of the building collapsed. Each of the eight niches comprised two subjects, one in the conch and the other on the wall immediately below it. In the sanctuary was a Christ enthroned, almost certainly over the apostles. Facing this, in the western conch was the Last Supper. It was framed by the portraits of the Evangelists. Luke is the only one still in relatively good condition. The painter Sargis kneels at Matthew’s feet, dressed in a long brown kaftan. The fine Armenian dedication inscription fills the entire upper area. The arches over the conches bore portraits of saints in medallions. On the walls immediately below, the layout is equally rigorous: the sanctuary was framed by the Nativity to the south and the Crucifixion to the north. Only fragments of the Transfiguration and the Descent into the Limbo remain. The style recalls the art of the miniature. The painter used classic Byzantine iconography.

Today the church stands damaged on its eastern side and isolated far to the left of the main track, close to the north east wall of the city of Ani. But once, a whole series of buildings stood around it that remain recorded in the inscriptions.

Interactive Plan