Ioanna Rapti

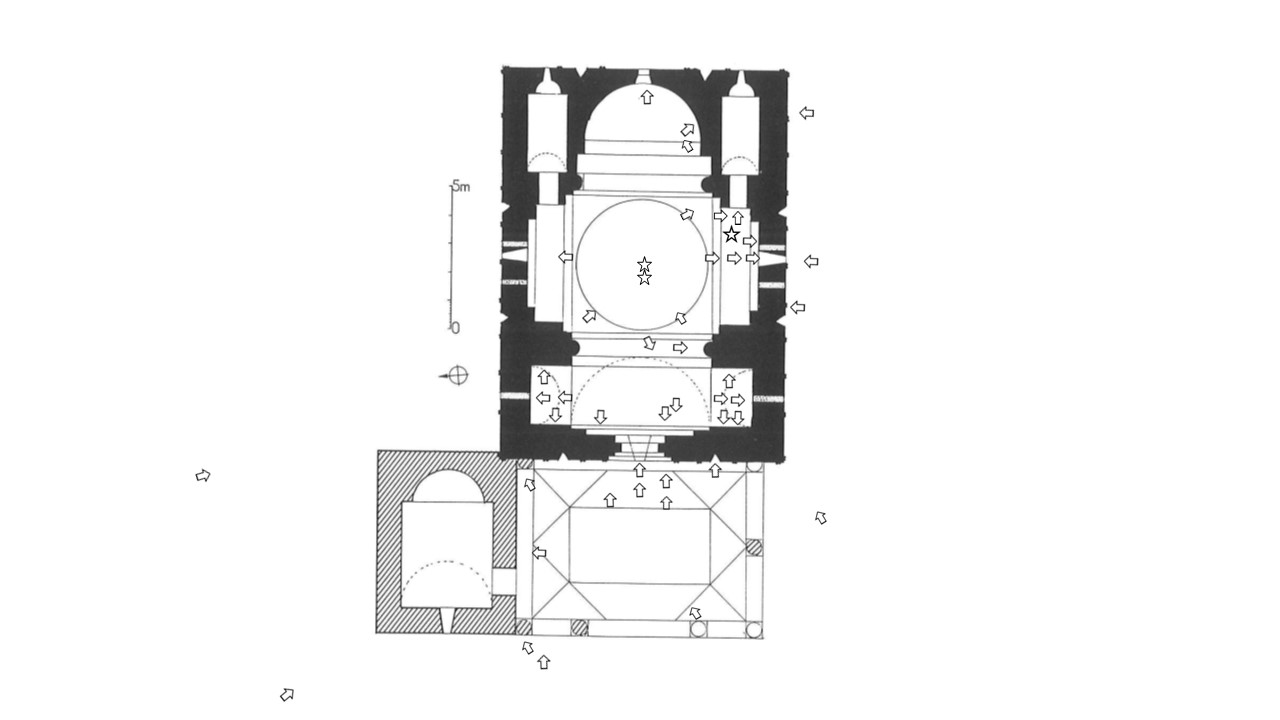

Located on a narrow terrace between the Bagratid city walls and the river, the church was built in 1215 as stated by the long inscription on the south façade. Its plan, the most common in Armenian church architecture, is defined either as a domed hall or cross-in-square type. The building measures 13,80 x ca 10 m. Four engaged pillars support the cupola on the top of a high cylindrical drum inscribed within a faceted polygon. The sanctuary is composed of a large semi-circular apse between two-storied side-chapels accessible from the nave. At the west of the building the ruined walls are considered to be the remains of a zamatun planned as a gallery, with open south and west sides and an adjacent chapel to the north. The façades made of local tufa are adorned with blind arches and elaborate sculptural decoration on the spandrels and on the facets of the drum. In the interior, a unique ensemble of frescoes combines the great feasts with illustrations of the conversion of Armenia by Saint Gregory the Illuminator and of the vision of Saint Nino, the female apostle of Georgia, alongside a series of saints’ portraits.

The church stands out as one of the most eloquent structures of the city. Its significance owes to its location, decoration and the founder’s will recorded on the south façade. The name of this single citizen has overshadowed the dedication to Saint Gregory the Illuminator and patron of the Armenian Church.

The eponymous church is a landmark in the cityscape but also belongs to a unique network of buildings related to the patron: in 1201, soon after Ani came under Georgian rule, a donation inscription at Horomos monastery, a major suburban institution in management of the city’s resources, states his wealth. Several inscriptions in the same monastery refer to Tigran’s house for the location of urban estate. Two years before the completion of the church, Tigran Honents’ makes a statement of authority about funding the restoration of the cathedral and celebrating his patronage in an inscription on the main façade close to that of the royal founder. The space for the amounts of the donation and the reward in masses is left blank suggesting that the patron’s attempt to appropriate the main sanctuary of the city may have not been entirely successful. The emulation of the cathedral in Tigran Honents’ church is indicative of the founder’s ambition and sensitivity to the city’s memory. Similarly, the dedication of one more sanctuary to Saint Gregory is perhaps not mere repetition but conscious perpetuation of Armenian aristocratic piety. The visual dialogue between 11th and 13th century monuments also fits with the appropriation of the Bagratid past, observable in many monastic sites in the Armenian lands under Georgian and later Mongol rule. Tigran Honents’s involvement at Ani seems as great as his influence and wealth. His patronage of the cathedral and of his own church complete each other and connect the city’s histories exemplifying social and urban evolution.

The sculpture underlines the shape of the building connecting 11th century tradition and 13th century decorative taste. Amidst the traditional bestiary, two interlaced dragons at the center of the southern façade ascribe the building to the shared culture of Anatolian patrons and point towards oriental silk imagery through Anatolia even before the Mongol conquest. They resonate with the frescos reproducing smooth silk hangings by the apse.

The double hagiographic focus on the patrons of Caucasian Christianity, has divided scholars regarding the origin and confession of the founder, often considered as a Chalcedonian Armenian. However, Tigran Honents’ identity should be outlined in terms of urban and social consciousness and exceptional personal ambition rather than ethnic or religious categories.

Tigran Honents’ church, together with the nearby Virgins’ monastery, raises the issue of urban monasteries since they depart from the well attested pattern of rural monastic spots of landholding and power. Since the founder’s burial was in the western suburban necropolis, the monastery was likely meant to secure the patron’s wealth and perpetuate his memory through the mediation of a community and the synergy of the illuminators of both Caucasian churches to which the elites of the time belonged.

Interactive Plan

Image Gallery

Bibliography

- Cuneo P., Architettura Armena, Rome 1988, no 424, pp. 658-659.

- Eastmond A., Inscriptions and Authority in Ani in N. Asutay-Effenberger and F. Daim, Der Doppeladler – Byzanz und die Seldschuken im Anatolien vom späten 11. bis 13. Jahrhunderts, Mainz 2015, pp. 71-84.

- Eastmond A., Other Encounters. Popular Belief and Cultural Convergence in Anatolia and the Caucasus, dans Islam and Christianity in Medieval Anatolia, A. C. S. Peacock, B. de Nicola and S. N. Yıldız eds, Farnham 2016, pp. 183-213

- Mahé J.-P., Le testament de Tigran Honenc’ : la fortune d’un marchand arménien d’Ani aux XIIe-XIIIe siècles, Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 145, 2001, pp. 1319-1342

- Maranci C., Medieval Armenian Architecture. Constructions of Race and Nation, Louvain 2001, pp. 26-27, 138.

- Thierry J.-M. et Donabédian P., Les arts arméniens, Paris 1987, pp. 477-488.

- Thierry N., L’église Saint-Grégoire de Tigran Honenc’ à Ani (1215), Louvain et Paris 1993 (with earlier bibliography).

- Mahé J.-P. and Karapetyan, The Hoṙomos Inscriptions, S., Hoṙomos Monastery : Art and History, E. Vardanyan ed., Paris no 40, 43, 56, pp. 369, 374, 387