A lot of work goes into marketing an exhibition, from nailing a creative brief to hitting the upload button on Instagram, there are many steps in between which are all as equally important.

As someone who spends more hours on social media than I care to admit to, taking on the role of marketing for the exhibition seemed a responsibility not too far away from the social media I knew. As long as we had a graphic designer on board and some beautiful images of the artwork, I anticipated minimal hiccups. I had a fantastic partner (and friend!) sharing the load – shoutout to Julie – and together we naively navigated the world of press and marketing.

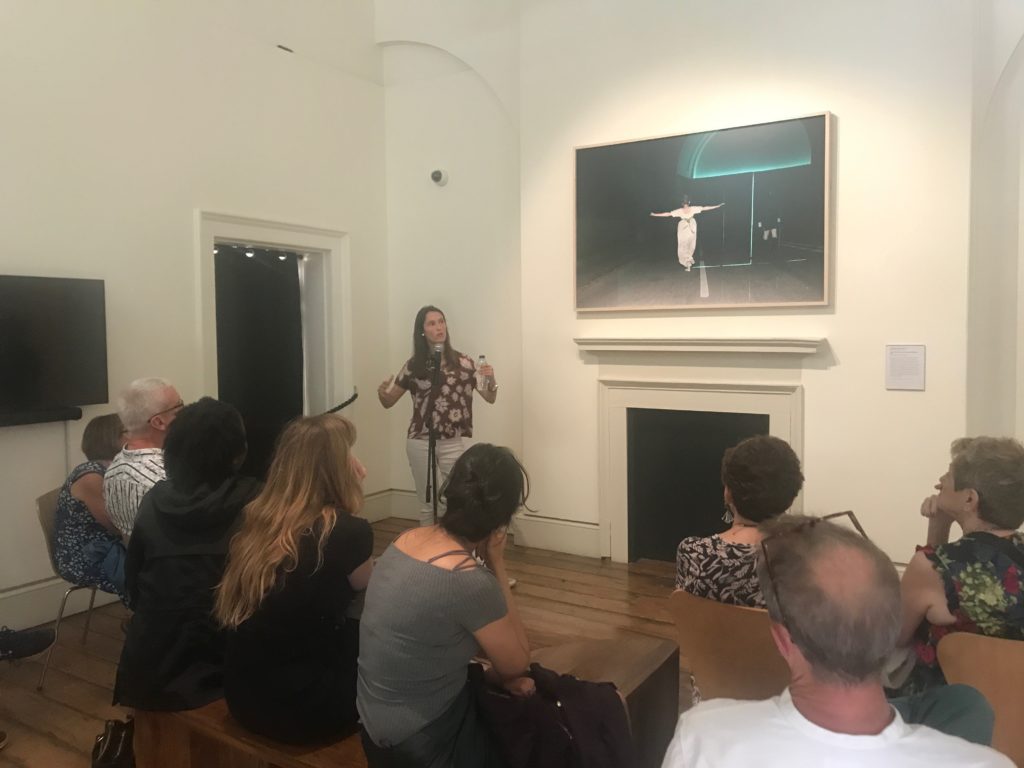

Our first task was to find a graphic designer. This sounded simple enough but with the added difficulty of a pandemic and lockdown, this was more of a challenge. Many hours were spent on Zoom calls with the rest of the gang, pitching potential designers and figuring out how we wanted the exhibition to look and feel. We eventually locked down (pardon the pun!) Mathilda Della Torre, who as it happened, had worked with the MA Curating group of last year and roughly knew how the exhibition process worked, though obviously this year was very different with no physical exhibition taking place. Mathilda was set to work, designing the beautiful posters and various other assets that are across the website and marketing materials. We are so pleased with the work Mathilda produced, and Julie and I definitely developed our problem-solving skills and the importance of taking a lead on something, particularly when it came to making decisions!

I can’t write a blog post on marketing without mentioning the press release. Once again, this was something both of us were completely new to but was such a valuable learning experience for us as well. We took advice from Ashleigh Toll, the marketing guru for the Courtauld, and drafted the press release, collated a press pack which included key artwork images and our events programme details. Personally, it was incredibly interesting seeing what goes on behind the scenes in order to get journalists interested and provide all the information they would need. Communication was key here, because of the multiple partners involved in our exhibition project. It was vital that everyone approved and was happy with the material we would make public.

Posting on social media was probably the most familiar task to us, and something I really enjoyed doing. We could get a bit creative on Instagram Stories and hopefully enthuse others enough to visit the exhibition. I will admit that after the show had launched online, it was harder to keep the momentum going on social media. I think this would have been very different had we been in a physical gallery space. A challenge we are currently figuring out is knowing when to stop posting about the exhibition on social media all together, we are now in full dissertation mode, yet the exhibition website is still up and running (and will be until June 2021).

A definite highlight for all of us was being featured as the ‘Exhibition of the Week’ in Jonathan Jones’s ‘Art Weekly’ article in The Guardian. Being recognised by one of the most well-known art critics in Britain is something I will not stop talking about for a long time!

As I mentioned at the beginning of this post, I’m not sure myself and Julie really knew what marketing an exhibition actually looked like, and although we made some obvious mistakes throughout the process, it was a fantastic learning opportunity and one I would certainly sign myself up for again, perhaps not in a global pandemic though.