This large cross, decorated with minutely carved scenes of the Old and New Testament, was used for the benediction of the congregation during the liturgy of the Orthodox Church. Its main body bears episodes from the Great Feasts Cycle, known as the Dodekaorton in Greek, essentially events from the life of Christ and the Virgin, while the foliate ornaments surrounding it are carved with Old Testament narratives and images of prophets and saints. A pair of Greek acronyms referring to the salvation of mankind can be seen on the lateral sides of the cross. The metal base was probably added in the nineteenth-century.

Individual scene narratives

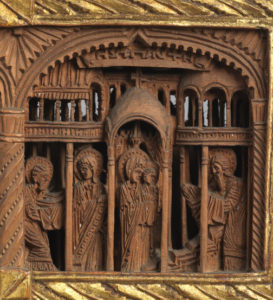

Each scene, identified by a relief inscription in Greek, is set underneath an arched opening and against an architectural background. The iconographic programme does not follow a strictly chronological order, yet further consideration reveals that the carver chose the position of each episode carefully. For instance, the central compositions on either side of the cross show two highly important events from the life of Christ: the Nativity on one side (A), and the Crucifixion on the other (B) – a pungent juxtaposition of life and death very pertinent to the symbolic meaning of the cross. The horizontal arms of the cross (side B) bear a sequence of scenes that evoke the idea of human redemption through death. From left to right we see: the Dormition (death) of the Virgin, the Crucifixion, and the Harrowing of Hell. These episodes are flanked by two Old Testament narratives also emphasizing the idea of salvation through God’s intervention: the Three Hebrews in the Fiery Furnace and Daniel in the Lions’Den, both taken from the Book of Daniel.

Click on sections of the cross to reveal close-ups and read descriptions of the scene narratives:

Redemption through sacrifice

A scene which does not really fit into the iconographic programme of this cross as it does not derive from the Bible, is that of the Apostles Peter and Paul holding a model of a church, which is carved inside the uppermost finial (side B). This theme, popular in post-Byzantine art, is thought to symbolise the union of the Orthodox and Catholic Churches. The idea of the redemption of mankind through sacrifice is also underlined by the acronyms incised onto the thickness of the arms of the cross: ‘ΤΚΠΓ ’standing for ‘The Place of the Skull has Become Paradise’; and ‘ΑΠΜΣ’ meaning ‘the Cross is the Beginning of the Sacrament of Faith’.

Monastic craftsmanship

Monastic craftsmanship

The most probable place of manufacture of this cross is Mount Athos in northern Greece, where a large number of this type and its variants are kept. The celebrated monastic community of Athos, consisting of twenty monasteries ‒ the oldest dating to 963 ‒ was a centre of miniature woodcarving between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. This craft is still practised by monks on Athos today.

Scholars in recent years have begun questioning and revising the provenance and dating of the so-called ‘Mount Athos’ crosses. This cross, traditionally dated to the 18th century, may in fact have been made one hundred years earlier. The large size of the cross, the added elements to the edges of its arms and in the spaces between them, as well as the absence of metal revetment all round seem to point to a seventeenth century date.

Provenance and Dating

Provenance and Dating

Scholars in recent years have begun questioning and revising the provenance and dating of the so-called ‘Mount Athos’ crosses. This cross, traditionally dated to the 18th century, may in fact have been made one hundred years earlier. The large size of the cross, the added elements to the edges of its arms and in the spaces between them, as well as the absence of metal revetment all round seem to point to a seventeenth century date.

Back to Mount Athos Cross