On 17 May, galleries reopened in the UK. I took the opportunity to visit From Here to Eternity: Sunil Gupta. A Retrospective at The Photographers’ Gallery for the exhibition’s limited reopening from 17 May – 31 May. A retrospective illumination of UK-based photographer Sunil Gupta’s (b. 1953, New Delhi, India) body of work so far, from 1976 to the present day, the showcase focusses on themes of race, identity, transition and family. Telling the story of what it is to be a gay Indian man, Gupta’s work is both personal and political, ordinary and melodramatic, and, crucially, challenges Eurocentric visualisations of bodies and desire.

I was particularly struck by the way that pose and self-styling affect the atmosphere of the photographs. In an interview in 2019, Gupta said, ‘[in] India … one of the major stumbling blocks to stepping into [a gay] identity was not having a place. Every time I met somebody the primary question was “Do you have place?”’. This notion was especially prevalent in three of Gupta’s photographic series on display at the Photographer’s Gallery: Towards an Indian Gay Image (1983), Exiles (1986-1987) and Mr Malhotra’s Party (2006-ongoing). The lack of place emphasises the importance of self-fashioning and the subjects’ poses and styling highlight senses of both displacement and belonging.

In 1983, Gupta created a black and white series, Towards an Indian Gay Image, that photographed Indian men who identified as gay. They agreed to be photographed but wanted to remain anonymous, which resulted in subjects posing with their back to the camera without their heads in the shot. Gupta explains:

It was the first time I had returned to India as an adult and I found gay men living in plain sight but completely hidden from mainstream society. The last thing they wanted me to do was to make photographs of them and publish them somewhere. It created a big dilemma for me as I was still in college and hoping to document social justice using photo-journalism and my subjects were invisible.

In these photographs, Gupta highlights the vulnerability of the gay community in India and the obstacles that arise from the desire to be recognised but the need to be hidden. He encourages us to consider how someone may dress and pose when they want to be both seen and unseen.

This duality is continued in colour in the later series Exiles (1986-1987), where Gupta returned again to Delhi to illuminate the lives of gay men in India before the decriminalisation of homosexuality. In 2020, Gupta told The Face, ‘I became aware through art school that this whole thing called art history is our context and my story is not in it.’ Exiles begins to tell this story, where clothing and pose are crucial in expressing Gupta’s subjects’ identity.

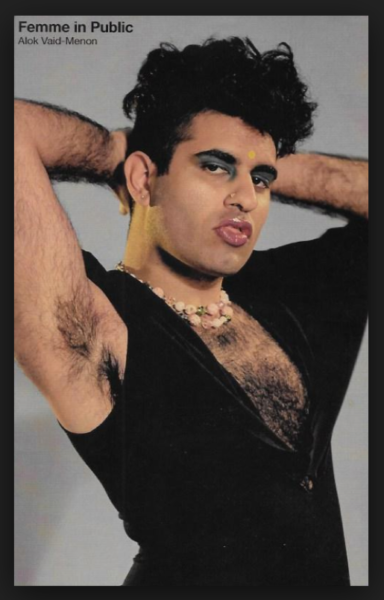

For a much later series, Mr Malhotra’s Party (2006-ongoing), Gupta photographs queer-identifying people in India, but this time they are keener to identify themselves. They pose confidently and look straight into the camera. The way they dress, too, is bold, cool, and assertive.

Across these images, a transition is clear: from invisibility to visibility. By putting physical photographs next to each other in time, the exhibition emphasised the role of self-styling and posing in displaying identities, and in telling crucial stories that are at once personal and political. Through these photographs, Sunil Gupta created visibility for those who were hidden and began to answer the question: ‘what does it mean to be an Indian queer man?’ As the photographer himself has said, ‘It’s our everyday stories that are important.’

By Kathryn Reed

Sources used

Artist’s own website, <https://www.sunilgupta.net/> [Accessed 19 May 2021]

From Here to Eternity – an original film with photographer Sunil Gupta, dir. Louise Stevens, 2020, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-N2AtpQEtzs> [Accessed 19 May 2021]

The Photographer’s Gallery exhibition press release, ‘From Here to Eternity: Sunil Gupta A Retrospective, 9 Oct 2020 – 24 January 2021’, (4 August, 2020) <https://thephotographersgallery.org.uk/whats-on/exhibition/here-eternity-sunil-gupta-retrospective> [Accessed 19 May 2021]

Cochrane, Laura. ‘Sunil Gupta: photographing India’s queer scene over 50 years’, The Face (8 October 2020) <https://theface.com/culture/sunil-gupta-art-the-photographers-gallery-from-here-to-eternity-exhibition> [Accessed 19 May 2021]

Dunster, Flora. ‘Do You Have Place? A Conversation with Sunil Gupta’, Imagining Queer Europe Then and Now 35 No. 1 (20 January 2021)

DreckMag, ‘Interview with Sunil Gupta’, DreckMag (1 January 2017), <https://dreck-mag.com/2017/01/01/sunil-gupta/> [Accessed 19 May 2021]