Starting in 1979 Richard Avedon began a project, commissioned by the Amon Carter Museum in Texas, documenting the American West. He spent five years traversing the western part of the United States taking portraits of average, overlooked people. The project concluded with an exhibition of selected works and a catalogue called In the American West. The magical quality of these photographs is in the immediate connection the viewer forges with subject. Looking at these photographs you begin to feel as though you know the person in the portrait. Part of this comes from the equalizing way Avedon went about taking each photograph:“I photograph my subject against a sheet of white paper about nine feet wide by seven feet long that is secured to a wall, a building, sometimes the side of a trailer. I work in the shade because sunshine creates shadow, highlights, accents on a surface that seem to tell you where to look. I want the source of light to be invisible so as to neutralize its role in the appearance of things”. Avedon created a blank slate where the personality of the subject could be freely expressed without any distractions. In this neutral space, the sartorial choices of the subjects come under greater scrutiny and become even more symbolic of their inner lives. What struck me as particularly interesting in these photographs was they ways in which Avedon photographed pairs and how their bodies interacted within the frame.

In Rusty McCrickard and Tracy Featherstone, Dixon, California 1981 a man and woman stand staring directly into the camera. The woman is dressed in matching tropical print shorts and a button up top, while the man wears jeans and no shirt. Their hands are clasped together in the centre of the frame. The man’s bare chest seems to blend with the white background and create a sense of negative space, contrasting with the woman’s vibrant print. While the man physically takes up more space due to his size, they share the frame fairly equally.

In John and Melissa Harrison, Lewisville, Texas, 1981 there is a sense of harmonious shared space as well. John stands facing the camera straight on. He holds his daughter in the crook of his left arm so that she dangles upside down in front of him. Her right foot hooks around his neck mirroring the angle of his bent arm. His dark clothing contrasts with her white shirt and diaper. Although he, like Rusty McCrickard in Rusty McCrickard and Tracy Featherstone, Dixon, California 1981, is larger than Melissa their intertwined bodies form one unit that sits in the centre of the frame.

In Teresa Waldron and Joe College, Sidney, Iowa, 1979, Teresa stands as the centre of the frame. She hooks her index finger into the pocket of Joe’s jeans, thus linking them together. Her white cowboy hat frames her face, while her light-coloured striped tank and dark jeans contrast with Joe’s silky shirt and lighter-wash jeans. Joe’s prominent, shiny belt-buckle draws the eye to him, yet his body is only partially in the frame. The portrait focuses in on Teresa, while Joe is pushed to the side.

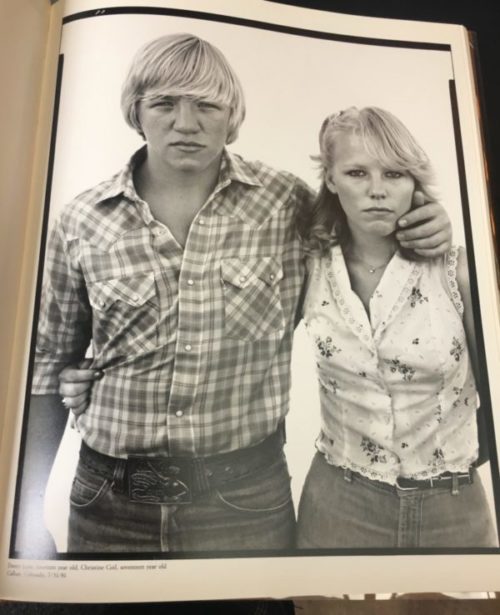

In Jonathan and Sam Stahl, Gilford Montana, 1983 this is taken a step further. While Jonathan, on the left, is prominently featured, Sam, on the right, is only half in the frame. Their matching checked shirts gives the feeling that they are connected. Sam’s arm seems to disappear into the Jonathan, thus enhancing the sense that they are one unit. That being said Jonathan is in the centre while Sam is cut off by the frame, almost as if Avedon capture their image while walking by them. The dynamism he finds in the contrast between bodies in his In the American West series is truly captivating.