Nancy Deihl has edited a fascinating compilation of sixteen essays each of which examines an American fashion designer whose work has been all but forgotten. The chosen examples are women who were successful in their day, and their style encompasses everything from custom-made to ready-to-wear, as well as demonstrating interconnections with the entertainment industry and fashion media. As such, it is a book that relies on forensic research of fashion history, and exposes the rich narratives of individuals who helped to build the American industry.

I was thrilled to see Tina Leser included in the list of contents. I have long admired her work, having become fascinated by the beautiful hand-painted blouses and dresses I saw in museum collections when researching my book The American Look: Fashion, Sportswear & The Image of Women in 1930s and 1940s New York. Written by FIT Special Collections Archivist April Calahan, the chapter reveals new details of Leser’s life and career that illuminate her progress and the significance of her work.

It is so interesting to read about her early married life in Hawaii in the mid-1930s, and how her glamorous, sportswear-inspired style developed when she opened a shop opposite a chic hotel, whose clients quickly became her key customers. Here, she imported leading designers from the mainland, including Nettie Rosenstein, and gradually built her own signature look, before she switched to the East Coast herself. She was prompted to move by a series of external events, from a shipping strike that cut off her wholesale supplies, to the bombing of Pearl Harbour in 1941. Once in New York, she began to work with manufacturer Edwin H. Foreman, and continued to grow her business over the coming decades, to become a significant member of America’s fashion industry.

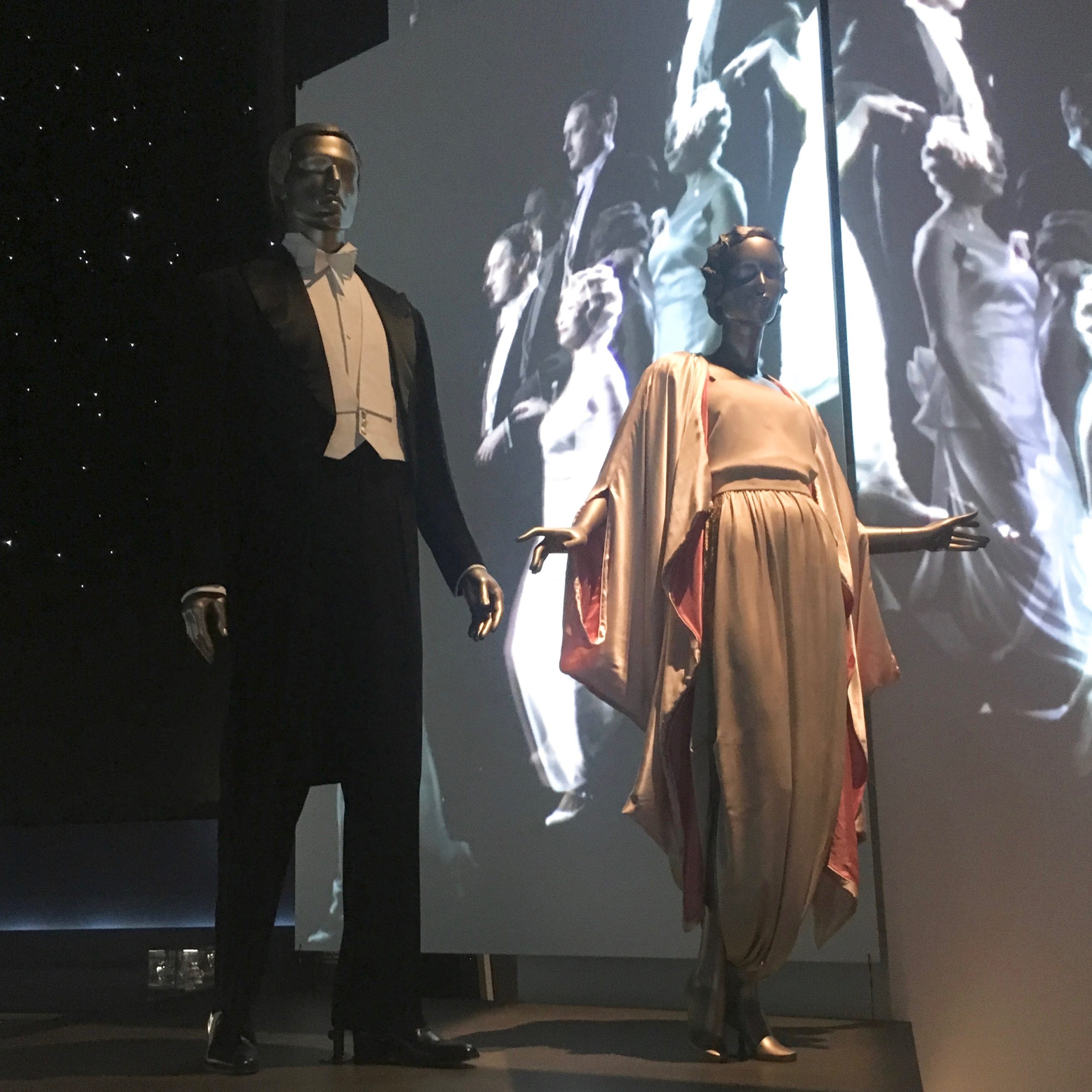

What Calahan’s essay eloquently shows is the way Leser’s career developed to include international influences in her use of fabrics and design elements, as well as her commitment to outsourcing production to other countries. She was, as such, a pioneer of globalisation, looking, for example, to Indian tailors to make up her designs, and seeking to create mutually-beneficial partnerships with her collaborators. Although not always as successful in execution, her dedication to overseas artisans is admirable, and adds a new layer of understanding to her well-known love of Asian references in her designs. Dhoti-inspired evening dresses, for example, are the perfect encapsulation of her version of the American Look – simple, fluid jersey forms given emphasis through their Indian silhouette.

Calahan’s chapter demonstrates the book’s strength as a whole – it celebrates female creativity and business knowledge – and will surely, as Deihl states in her introduction to the compilation, inspire further work on America’s myriad fashion talents.