Emma McClendon was the Associate Curator of Costume at The Museum at F.I.T. in New York where she has curated numerous critically acclaimed exhibitions including Power Mode: The Force of Fashion (2019), The Body: Fashion and Physique (2017) and Denim: Fashion’s Frontier (2015). She graduated from the Documenting Fashion M.A. program at the Courtauld in 2011. She sat down with Helena Klevorn to talk about fashion’s position in the museum, burgeoning questions about fashion curation, and her next career steps.

HK: HI!

EM: Hi! How are you? How is everything going?

HK: It’s good, though kinda tough, as you can imagine since the school has closed and we all went home and are writing our dissertations at home.

EM: Oh, you’re doing that all remotely. When did you guys comes back?

HK: I think most people left around mid-March.

EM: Oh, that’s not too long after I saw you guys, right?

HK: Yeah, it was really soon after our visit that the school closed. Everything happened so fast! So, the first think I want to talk about, since you told us you went straight to F.I.T. from the M.A., was how from the beginning of the M.A. program to the end, your idea of what you wanted to do afterwards changed or if it didn’t change, in that you got to do exactly what you wanted straight out of the program.

EM: I think it’s kind of weird because I think that I went into the M.A. program absolutely hoping that in the long run I would be able to work in a museum and work in a curatorial role at a museum that dealt specifically with fashion, because what led to the program was that I had interned in the Furniture, Textiles, and Fashion department at the V&A while I was an undergrad. I had actually worked with a furniture person, not a fashion curator, but while I was there I met some of the fashion curators and they had all gone to the Courtauld and so that was what led me to look into the program and so that was the dream. But while I was in the program, I definitely went in with eyes wide open that the likelihood of getting a curatorial job in a museum was pretty low. It’s a niche field, there just aren’t a lot of institutions, unfortunately—now there’s more and it’s growing—but even just ten years ago there weren’t as many institutions as there are now dealing with dress and fashion.

So throughout the program I kind of explored other ways that I might work in tangential fields. I did an internship while I was doing my M.A. at Diane von Furstenberg’s office in London during market week because I was like, “Well, maybe I can parlay this into the fashion industry itself.” I also did an internship, and these were shorter Work Experiences, at I.B. Tauris, the publishing house, just to get a lay of the land because, again, this [my current position] was the goal. It sounds really linear and like it was perfectly planned when I say it now, but at the time it felt like anything but a sure thing. That was the goal but in that way that I almost wouldn’t say it out loud because it sounded so far-fetched at the time.

So I started [at F.I.T.] as an intern, and even while I was interning it still seemed like a long shot, because of, I think, one of the most useful pieces of information I heard during the program from the working professionals that we met—like Beatrice [Behlen, Senior Curator of Fashion and Decorative Arts], who I’m sure you met at the Museum of London. We went on a trip to their archive and saw a few pieces and I remember her being really frank with us in a way that I always try to be with students when they come through, and she said that museum work can be all about timing, which is what’s really frustrating because these are jobs that people tend to stay in for a really long time and there’s not that many of them and so it can really be about just happening into it. Yes you do the work, and you try, and you get the degree and all that, but it’s also being in the right place at the right time. And in that way I do feel like I was very fortunate that when I was coming to the end of my internship a part-time job opened up in the curatorial department, and so I applied and I was fortunate enough to get it, but then I was in that for almost two years before I got the full-time job. So there’s timing, and also this field just takes a lot of patience, is what I would say.

But, again, another thing I always say and what I really do believe from my experience is that even though it seems really scary, and the pessimistic way to look at it is that there’s no right way to do it, there’s no path, there’s no funnel and step-by-step process that you’re supposed to follow and that’s mapped out for you, that can be so frightening. But the more optimistic way to look at it, which I really do think is true, is that there’s no wrong way to do it. Because of the way that this is such a niche and burgeoning field, people are coming into it and coming into museums and coming into academic positions from all different angles. People are working in corporate archives, they’re working in journalism, they’re working in the industry itself, they’re not necessarily just interning at a museum and working in a museum. There is a much broader spectrum of how you can build your career and build your experience.

HK: Definitely. And on that note, I wanted to talk about how, especially as you’ve been in this position for a number of years now and seen it change, I’m seeing people coming up as “independent fashion curators.”

EM: Right, yeah.

HK: There was a woman who I saw speak a few years ago who, then, was a curator at Somerset House, and then moved to New York City and now is an “independent curator” unaffiliated with any particular institution. What does that kind of position mean in this space and the, sort of, ability to be curating fashion outside of a museum and what do you see in that in terms of the direction it’s moving in?

EM: I think that’s one of the things that’s really exciting. I, personally, would like to see more institutionalized, full-time, permanent positions for curators in our field given that museums and institutions generally–like colleges and their art galleries or corporations or independent galleries–are sort of hungry for this topic and want to engage with fashion, but then they don’t employ the permanent person, and that’s where these freelancers come in. And so this is where I think it really is about there not being a clear cut path. You can freelance, I know so many people who are in this field and [freelance] is the path that they’ve been on, whether it’s that they don’t like the 9-5 or whether it’s that they’ve really kind of struggled and hustled and this is their way of doing curatorial projects. Again, there’s a spectrum of how people come into this. But I think it’s really exciting.

I, personally, have not yet done a freelance project. Because of the trajectory I’ve been on, I’ve always been with an institution which is really fortunate, but it also, I think, can be kind of limiting. When you’re a freelance curator–and there are so many opportunities for that because people are so hungry for this project and that’s just what a lot of people have to do–I think you have to wear so many different hats when you’re doing that job, because not only do you have to be the person who thinks of the ideas, thinks of the objects you want to include, thinks of how you want to organize the space, you also have to be the person who organizes the space, who organizes how you’re going to build it out, how you’re going to get it to look the way you want it to look. You might have to dress all the objects, because you might not have the money to employ handlers or installers. You also have to manage your entire budget and a lot of times that’s down to managing how much you’re actually going to be able to pay yourself. And I think that in museums, also, there’s a whole spectrum of museums, less well-known museums or historical houses, where you have to do a similar thing to the freelancers and wear so many different hats while you’re doing those kinds of projects.

In a way I feel kind of conflicted about it because I think it’s really exciting that there are all of these freelance opportunities and that there is this outlet to be able to express yourself creatively. At the same time, I worry that so many institutions are taking advantage of this freelance workforce that’s out there so that they can put on these one-off shows that maybe travel from somewhere else and then hire a local person or even not even a local person, a remote person, to sort of oversee or “advise” the curatorial staff at the museum. But then, [the institutions] don’t actually have any experience in mounting a fashion exhibition and it’s so different that I think it can be a double-edged sword. But I do think it is something really exciting and I would encourage anyone who’s entering the field to consider [the freelance] avenue. You know, if you have a project if you have an idea and you want to workshop and approach a gallery, an institution, a place, if you have a means or a context to get mannequins, get objects, you know, there’s a lot of opportunity there.

HK: Going off of what you were talking about, with the institutions and how they’re treating these exhibitions, your institution is obviously very focused on fashion and displaying fashion, but in other institutions where that’s something they’re starting to explore or that’s a department within a larger, fine-art focused institution, what do you think is the attitude towards fashion exhibitions? I’ve heard that it can be, “Oh, well, that’s a money-maker that gets people in the door but it’s not necessarily something we value.” Versus, for example, the V&A where they have, for lack of a better word, a higher regard for clothes than other ones. So I’m curious about how you’ve seen that transform or not transform.

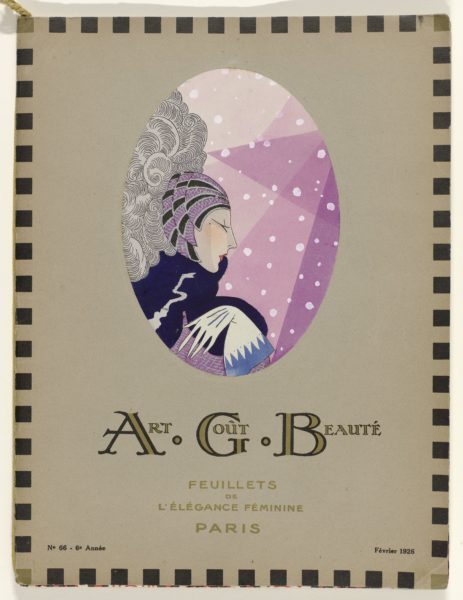

EM: Well, museums and their approach to fashion is very much based on the goal of the institutions, right? So I think the attitude towards fashion can very based on whether they collect fashion or not. I think a place like the V&A started as a decorative arts museum, and they’ve been collecting textiles and clothing and material objects for their entire existence, so they’re going to have more of a regard and have more flexibility to let fashion be fashion and not have to fit it into a box. Whereas, similarly and different, a place like the Philadelphia Museum of Art, also has been collecting fashion, for a very long time, and it has one of the older collections of clothing in the states. But that’s a fine art museum so I think that, likely, when you’re part of a fine art museum, you have to position the exhibitions within the goals of the institution, which might be more about the theories, and critiques, and ideas behind fine art as opposed to material culture or even social history. Versus the Smithsonian, their approach is going to be completely different, and it’s going to be about where clothing fits into the broader scope and mission of the institution because it’s sort of a social history museum.

But I think what’s been interesting to see are the places that, only in the last decade, have started to show clothing. What I find most interesting to see about those institutions is whether they’re going to develop their own content or whether they’re going to bring in a travelling exhibition because I think that can kind of change the institutional attitude towards it. if you’re just bringing in a monograph designer exhibition, like about Dior, about YSL, about something like that, in my opinion those shows are really about being a blockbuster. They’re about getting bodies into the museum and, yes, celebrating fashion, and yes celebrating these objects, and yes welcoming it into the museum. It’s great to see so many more museums doing these shows, and that’s the majority of the one’s that we’re seeing expand in the field, are these travelling blockbusters, you know Gaultier, McQueen, Dior, YSL.

What is much fewer and far between are when we see a show like the one at MoMA that doesn’t have a clothing collection, that has some odd objects that you could define as dress, but they developed from the ground up an entire show that was original to MoMA. And there were a lot of mixed reactions to that, because, you know what was interesting about that show was just how many reactions it sparked from people, from people from art who were like, “what is this doing here?” to people in fashion who were like, “I don’t know about their approach,’ but I’m still kind of processing how I feel about it. One thing with that show is that I think it’s fascinating that a museum that doesn’t collect [fashion] still developed its own content and brought this show and that it was able to spark such conversations about the topic. I wish more museums would do that, but unfortunately we’re really seeing that—and I mean this is true for fine art exhibitions as well—the big artists, the big designer exhibition is the kind of general governing principle for museums that don’t do fashion dipping their toe in the water or fashion. They’re not necessarily going to do a thematic deep dive trying to grapple with it academically, but we’re only really in the first, kind of, ten years of this awakening of interest, and I mean big blockbuster interest.

I keep using this word blockbuster and you brought this up in your question, it is about money, and I think it would be wrong to exclude money from any discussion of museum content and museum planning. Yes we, ideally, want the museum to be a place about ideas and academia and where money is this thing that you disregard, but the reality of running museums is that it’s always thinking about how many people are coming through the door, what the budget is, what you can put on, what loans you can get, what objects you can acquire, and so I think that this global interest in fashion exhibitions came out of the insane numbers of the McQueen show.

There is a reason that I say this past decade because when Savage Beauty opened in 2011 at the Met, they hadn’t had things like that at the Met since, like, the Mona Lisa was on display, and it’s only been getting bigger and bigger since then, but that was one that came out of left field. That was the first one where it was like, the idea that fashion exhibitions happen that people are interested, because no one really even paid attention to the Met Gala that year. That was just one where he was so much in the public imagination because of his recent death, because Kate Middleton had worn a design by Sarah Burton from McQueen to the Royal Wedding, his name was out there, everybody was kind of talking about him and thinking about him, and it just hit at that perfect moment. The lines! I mean, I went to that and, that was when I first got back to the city, and the line went down the Met stairs and a couple blocks up Fifth avenue, it was crazy. And you got in and it was so densely packed, and I remember that year the last few days of it they kept the museum open until midnight or something and there were lines stretching inside also to get to it. And so when you’re in the museum field you really are always thinking about how to get community engagement, visitor engagement, get bodies in the museum, that’s how you run your institution. It’s going to raise your eyebrows and make you ask why and, of course, since then, we’ve seen more and more institutions…

HK: …Taking that on.

EM: Right.

HK: It’s interesting that you bring up the issue of money in the exhibitions and the presentation of these pieces, because, especially with my background in formal art history, I feel as though something that was always coming up in the conversation was showing pieces that theoretically you could buy. Not off the mannequin in the museum but, for example, I could go to a show about Dior and if they show something from the last season I could go buy that. Or at the Rei Kawakubo show, a couple of years ago, they had the Commes des Garcons PLAY T-shirts in the store. The intersection of that is something that I don’t have an issue with, and that’s mostly because I think if you consider a garment as a piece of important work then you’ll consider your purchases more seriously, but I’m not sure if that really happens or if it affects people in that way.

EM: I think that there is a kind of cynical way to look at it and then there’s a much more generous way to look at it. So I have two minds about it. One is that at the end of the day, I do not think that fashion is art, personally. Fashion is an industry, fashion is material culture, fashion is not fine art. Fashion is a consumer product, that’s made, as you’re saying, in a completely different way. And when you’re showing contemporary clothing, it is a product, and, yes, I think that, again because museums—and this is the cynical thing—because museums are not for profit but they need money to run, and people also want these big flashy blockbuster shows, I think places like what you described with the Kawakubo show, they also had it with Camp, it’s like, yes we can poo-poo fashion as being really opportunistic, but museums do that all the time. I mean, every exhibition you walk out of you immediately walk into the gift shop, where the catalogue is and the postcards are, and the tote bags are and the posters are, so this isn’t just a fashion thing, this is museums in general.

What I find personally, as a scholar, more interesting are shows that really make you confront, and these are few and far between, but shows that are more intentional about the integration of the consumer-side of fashion in the gallery space itself and making you confront that. There have been two shows that spring to mind, one was this tiny show that the Whitney had that was with Eckhaus Latta….oh gosh was it called…

HK: I can’t remember what it was called [either], but they sold the stuff in the gallery.

EM: Yes. So it was basically, you walked in and I went and I actually bought a piece that was there and it has a tag on it … hold on it’s right in the closet I’ll grab it. EM steps away from computer…My husband’s saying it was called “Possessed.”

EM returns with her token of gallery visit, a white denim jacket, that’s “got the cropped, kick-pleated whatever thing.”

EM: OK, so, because I’m nerd I kept the tags on it, but I got this there, and I’ve worn it, but I kept the tags on it because it has this thing that says “Special Museum Exhibition Product” and it also says that on the label … So anyways, I kept that because I thought it was so interesting, it was like one of the only times where I’ve seen, like you walked in, you didn’t have to pay to get into it, you know it’s like the Whitney you have to pay exorbitant prices to get in, this was in their…

HK: That downstairs gallery on the first floor

EM: Right, the small artists gallery that you don’t have to pay to get into. And so it also kind of blended the space, and it was in the Meatpacking, so it’s blending the space between the museum, and the boutique, and there was, a photo spread when you first walked in on these lightboxes that were on the ground, it was very cool. And then you walked in and it was a staffed boutique, but [the fashion’s] the art, but it’s also an installation, but what I thought was most interesting was that they weren’t restocking it. So it was like, you go in the beginning, and it’s full, and they were very playful about it, they were like, “We don’t know if we’re going to sell anything, we might be full the whole time, we might end up being empty.” And they worked with local artists to create the space. And then it had a fitting room and it had all these mirrors up…Did you go?

HK: I read a lot about it, but didn’t get a chance to see it. But it’s certainly something that [even though I didn’t see it] stuck in my mind as a sort of “what was that?” moment.

EM: Right, right. And you walk in and then there’s another room and you realize that the mirrors in the shop are actually two-way mirrors into this other room that’s all dark and has seats you cans it on, and then it has this screen of monitors that are all showing live security feed to other stores around the world that sell Eckhaus Latta.

HK: Oh whoa.

EM: So that was one of the shows. A the other one, I think I don’t know that much about it because I didn’t go because I’m not in Chicagp, but last year there was the Virgil Abloh show.

HK: Yeah, that one I actually did get a chance to see.

EM: That one I know, just from a friend who lives in Chicago, that they also had this sort of merging of gallery and shop space. And again, this sort of presentation of clothing that’s on hangers and on a rack and how you would see it in a store, and being a gallery and not on mannequins, so this is all a very extended way to say that I think people who call out fashion exhibitions for doing that kind of cross-branding and object-selling are forgetting that that’s just what museums do all the time with their posters and umbrellas and, like, MoMA’s design store.

It’s like, I’m sorry this is just the business model, this isn’t fashion, it’s just that fashion maybe lends itself much faster because you can buy the thing that you’re seeing, or a version of it. But, what are you talking about when you can go buy the salt and pepper shaker by the fancy Italian designer that you’re seeing across the street at the MoMA design store, I mean MoMA’s been doing this for decades.

But again, I think that more compelling academically, are the things like the Eckhaus Latta, which, again, got such mixed reviews, but I was like, this is making you confront the fact that fashion isn’t art. It’s a completely different social mechanism, it’s an industry, you can’t talk about it in the same way and to put it up on a pedestal can get really problematic because then we’re not dealing with the labor and the people who wear things and we can put it up on a skinny white mannequin and call it art and be like, “Oh it’s O.K., because it’s idealized” and it’s like, well but it’s actually a real world product.

HK: Right. And to going on this, too, I think there was an interesting moment at the Abloh exhibition where they had his pieces on racks in the gallery, and I was standing with my mom, and they weren’t facing forward because they weren’t on mannequins, they were on racks.

EM: Right! Yes!

HK: And we were looking at it, like, are we supposed to touch them to see them? Like I’m at a shop?

EM: And you want to, and it’s this confrontation of how you interact with objects, and you put them in here and suddenly you can’t touch them. Yes, yes, that’s what I heard too. But it’s weird because you can’t see it and then you’re, like, wait what am I supposed to do?

HK: Yeah. And I think it’s really interesting, and it’s such a question because I wonder, you know, what does that mean in terms of, like, you see museums doing that and the other side is you see stores, like we visited the McQueen flagship store as a class.

EM: Oh, yeah yeah.

HK: We saw the exhibition of their couture on the second floor, and it opens this question of whether the gallery exhibitions are the same thing, or are they different.

EM: Yeah exactly, and that’s really interesting, because that was in London, right?

HK: Yeah, it was.

EM: Yeah, I was wondering about that too, because it’s at the boutique, but then are they selling them?

HK: Yeah, and you have to walk through the whole boutique to get up there, because it’s on the second or third floor, so you go through, you see people shopping, you see all the merchandise, and then you get to the top where they have the exhibition space.

EM: Yeah, exactly, it’s really interesting.

HK: So there are only a few minutes before Zoom is going to kick me off, and I wanted to ask about your next steps, since I know you’re leaving F.I.T. to go into a Ph.D. program, and I wanted to ask about that.

EM: Yeah, so I actually started the program part-time last year, and since I left the Courtauld program I always kind of wanted to get the Ph.D., and so I’m finally doing it. I basically just reached a point where, I’ve been at the museum for nine years, and I really felt like I got to a place in my practice where I was feeling really conflicted about a lot of issues with fashion and museums. I think about how its displayed, about how people react with it, about the mannequins, about the type of clothing that we’re showing, about the bodies that we’re showing, about the designers that we’re celebrating about the clothing that we’re collecting, and I feel a bit, kind of, conflicted about some of that stuff. I don’t necessarily have an answer to it, it’s not that I say, “Poo poo on all that stuff and it’s terrible” one way or the other, but I found myself just really wanting to take a break from active curatorial practice, and segueing into a more academic side.

I’m doing research at the Bard Graduate Center for my Ph.D., which I’m really excited about. It’s on the history of standardized sizing in the late nineteenth century in the U.S., and I’m also going to be teaching some courses at the Parsons M.A. program on curatorial practice, and object based research. I’m really excited to transition into a side where I can think about a lot of the issues that I was so involved with and didn’t have time to really reflect on. You’re constantly producing and you’re constantly in it when you’re working, and I’m excited to step back and take it in a bit because I do think that we’re on the cusp of a lot of change in museums in general between the pandemic, but also all of the much overdue conversations that are being had about equality and about representation and so it’s going to be really interesting to see how museums grapple with these things going forward. And particularly in fashion museums that deal so much with bodies and people and identity. So I’m excited to go into a different thing. I’ll miss curating as well, but it was really breakneck at the museum. In nine years I did seven exhibitions, and three books and a journal … it was amazing but it was a lot.

Quick Q’s:

- What was your M.A. Dissertation topic?

I wrote my MA dissertation on the effect of the 1962 Telstar satellite (which made it possible to broadcast live TV from around the world) on the trans-Atlantic fashion industry, looking specifically at how it impacted coverage of Paris couture shows in the New York Times and the New York Herald Tribune.

- What’s your favorite exhibition you’ve put on so far?

This is hard – I’ve really loved every show I’ve put on and each one has taught me new things and raised new questions that have built on each other. But if I had to pick one, I think it would be The Body: Fashion and Physique because it dealt with body positivity, discrimination, and acceptance, which is a topic that’s very important to me, and the exhibition actually gave rise to my Ph.D. research on the early history of standardized sizing.

- What’s an exhibition you didn’t get the chance to put on, but hope to see materialize in the future?

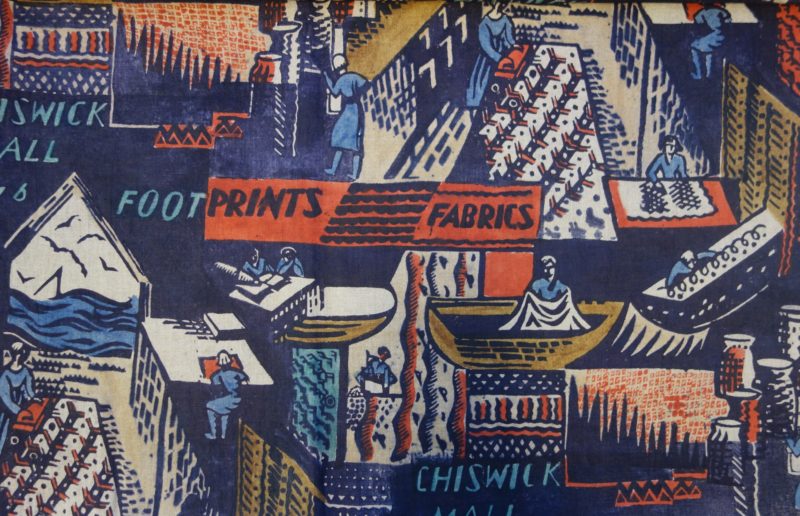

One issue I’d love to explore one day is the link between workwear and high fashion, and also the link between modern fashion, archaeology, and colonialism.

[Answers have been edited for clarity]