Over the weekend my Instagram feed was graced by an image of Audrey Hepburn (Eliza Doolittle) at the Ascot Races from the 1964 classic film My Fair Lady. I was immediately struck by the photograph, not solely for its aesthetic splendor but rather by the questions it raised in my mind surrounding the relationship of high fashion to sportswear within an Edwardian equestrian microcosm. It may also have left a lasting impression as it reminded me of a black and white cocktail dress which has been lingering in my online shopping basket for a number of weeks now, but that’s beside the point. In any case, throughout this blog post I’d like to discuss the fascinating juncture of style and sport which has manifested itself throughout history at the cultural scene of the horse race.

The professionalisation of sport at the turn of the twentieth century marks an important moment when looking to understand the existence of horse racing events as platforms for fashionable display. The social and economic character of spectatorship shifted radically towards consumption and the need ‘to get people through turnstiles’. This helped foster the symbiotic relationship between the crowd and the actual sporting event of horse racing as the audience became part of a now choreographed performance of athletic spectacle. The centrality of the spectator to the races, and, further, the significance of the clothes they wore as an essential element of the sporting event is thus highlighted, as aesthetic display became inherently tied to the successful execution of the affair. Dress historian Valerie Steele explains how fashion ‘can only exist and flourish in a particular kind of dramatic setting with knowledgeable fashion performers and spectators’. A horse racing event can therefore be understood as an occasion placated upon an attendee’s dual responsibility to contribute to the overarching fashionable spectacle, and to equally function as an aesthetic viewer. The fashionable spectator was not relegated to the side-lines of the event taking place, but rather played an active role in generating the action which characterized race-day culture. The crowd, and those elusive celebrities or flamboyantly dressed individuals which composed it, were as much sights to be studied as the horses and jockeys themselves.

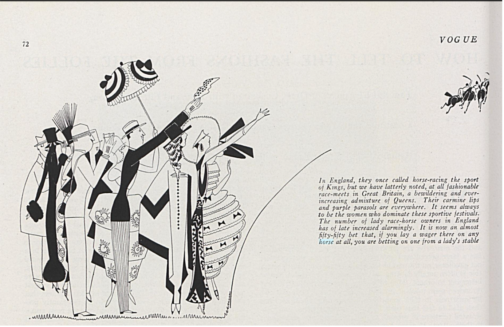

Consumption lies at the heart of horse-racing fashion culture in terms of both garment shopping and the subsequent reporting of the events in newspapers and magazines. From the early 1910’s the emerging allure of race-day fashions can be charted throughout print media, as the sporting occasions became voyeuristic opportunities to ogle at the extremities of ostentation. In this sense it is clear to see how horse racing fashion served as yet another social catwalk for an elite class who had disposable incomes sizable enough to afford both a race day ticket and outfit, as well as funds to spend on betting. In this way I feel that the advent of an elaborate media coverage at these events elevated their societal weight. To quote the article featured in Figure 2, ‘The apogee of fashion is reached at the spring Paris races and horse shows where the modes worn by the smart world receive their final stamp of approval’. Clearly, race-day fashions were viewed as social barometers to the current state of stylish aesthetic taste, yet, what I believe differentiates them from other forms of public display are their inherent ties to affluence. Unlike other forms of entertainment such as the theatre (which was becoming increasingly accessible to the general public at the turn of the twentieth century), horse racing retained a level of exclusivity which rendered its fashions deeply aspirational.

The rarefied environs of the Royal Enclosure at a race such as Ascot, alongside a crowd composed of well-known figures and public leaders served as a direct taste-making source for the socially aspirational. Using print media this influence was aided in its spread across previously oblivious sections of society, and thusly race-day fashions became associated with a wider public understanding of taste.

At this juncture the emerging place of sportswear within the wider ‘equestrian-wear’ culture of the Edwardian period should be addressed and noted as distinctly separate from the conversation held thus far surrounding extravagant race-day fashions. By the end of the 19th century it was becoming exceedingly evident that the traditional, ornate women’s riding attire of earlier periods was fading in popularity. To quote Power O’ Donaghue in Ladies on Horseback from 1889 – ‘A plainness (…) is to be preferred before any outward show. Ribbons, and coloured veils, and yellow gloves, and showy flowers are alike objectionable. A gaudy “get-up” is highly to be condemned, and at once stamps the wearer as a person of inferior taste. Therefore avoid it.’ The image below can be considered an exemplification of this dying style.

Women constituted almost half of all competitive horse owners by this period, and thus squarely located the culture of the sport within an increasingly feminine sphere. In this sense I feel that both in practical and deeply artistic terms the fashions of the equestrian world during this revolutionary period offer an insightful perspective on the nuanced state of early twentieth century femininity. Whether parading in a Royal Ascot dress or donning a pair of jodhpurs in a stable yard, an exploration of equestrian fashion conventions provides a compelling platform from which to analyze a period of significant historical upheaval.

By Victoria FitzGerald

Sources:

Goodrum, Alison. ‘The Style Stakes: Fashion, Sportswear and Horse Racing in Inter-war America’ Sport in History 35, no.1, (2015), pp.46-80.

Steele, Valerie. Paris Fashion: A Cultural History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), 247-264.

https://www.equilifeworld.com/equestrian-lifestyle/horses-fashion-history/