There are many different strands to the Digitisation Programme and I’ve been lucky to have researched and written a number of photographer’s biographies. Recently I came across a very interesting thread amongst a group of German/Austrian art historians and photographers linked by politics, persecution and war.

In the late 1920s and 30s the rise of the National Socialist German Workers Party (Nazis) brought about changes within German society that led to the persecution of many ethnic minorities and ultimately World War II.

Under the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler the term Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) was used to describe Modern Art – both German and international as it was viewed as being an insult to nationalistic German feelings. Anyone perceived as being responsible for the creation of such art and those who purchased and displayed it in museums and galleries across the nation were sanctioned and in many cases dismissed from their posts. These actions led to many so called ‘degenerate’ works of art being taken off display or placed in storage – some never to be seen again.

In September 1933 the Reichskulturkammer (Reichs Culture Chamber) was established under the control of Joseph Goebbels – Hitler’s Reichs Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda. He decreed that only artists who were “racially pure”or supportive of the Party would be allowed to be involved in the cultural life of the ‘new” Germany. By 1935 the Reichs Culture Chamber had over 100,000 members.

Modern art styles were prohibited, with the Nazis promoting paintings and sculptures that were traditional in tone and which exhibited values of racial purity, militarism and obedience. These same restrictions were applied to films, plays and music – especially jazz which was seen to stem from black influences.

In 1937 Die Ausstellung “Entartete Kunst” (The Degenerate Art Exhibition) was organised by Hitler’s favourite artist Adolf Ziegler a member of the Nazi Party since the 1920’s.

Under the direction of Goebbels, Ziegler headed a five man commission that toured state collections in various German cities and seized over 5,200 art works deemed to be “degenerate”. The works were taken to Munich – the fervently pro-Nazi Bavarian capital to be installed at the Institute of Archaeology in the Hofgarten. This venue had been chosen especially for its rooms which were dark and narrow and provided the desired depressing atmosphere.

The Führer was the arbiter of what was considered “Modern” and on the eve of the exhibition opening, he had made a speech declaring “a merciless war” on cultural disintegration, describing the people who produced such art as “incompetents, madmen and cheats”

To further emphasise their distaste and disgust the organisers decided that many of the paintings were to be displayed without frames, hung at angles and partially covered or accompanied by derogatory slogans such as:

“An insult to German womanhood”

“Nature seen by sick minds”

“German farmers – a Yiddish view”

and as a reference to the museum and gallery directors loathed by the regime:

“Even museum bigwigs called this “the art of the German people”

The exhibition contained paintings, sculptures and prints by 112 primarily German artists and also works of art by Picasso, Chagall and Mondrian which had been confiscated by Ziegler and his cronies.

Some of the paintings had labels next to them detailing the amount of money a museum or gallery had spent to buy them. Prices were greatly exaggerated using costs based on the post WWI Weimar hyperinflation period where money had been devalued. All of this was designed to promote the idea that “Modernism” was a conspiracy by people who hated German decency (without a hint of irony !) and that money would have been better spent providing citizens with food or essential services.

Die Ausstellung “Entartete Kunst” was timed to coincide with the “Grosse Deutsche Kunstausstellung” (Great German Art Exhibition) – a showcase of art by German artists approved by the Nazis. Over 2 million people had visited by the time it closed on 4th November 1937. By comparison “Grosse Deutsche Kunstausstellung” was viewed by half that number.

After Munich, it toured other cities such as Berlin, Leipzig, Düsseldorf, Vienna and Salzburg where another 1 million people visited.

Children were denied entry to these exhibitions due to the perceived harmful and corruptive nature of the works of art.

After the exhibition had completed its tour of Germany and Austria, many of the paintings which had been seized were sold to foreign art dealers who were assured by the regime that the proceeds would be used to upgrade and replenish collections in Germany’s museums. This was not true and most of the money raised went to fund the massive increase of Germany’s armed forces and armaments. In 1939, the authorities burnt over 5,000 works of art that it could not sell.

Photographs contained in the Conway Library, and part of the Digitisation Programme are attributed to Drs Georg Swarenski, Alfred Scharf, Ernst Nathan, and Susanne Lang. They were all of Jewish faith or origin so at risk of dismissal from their jobs or worse.

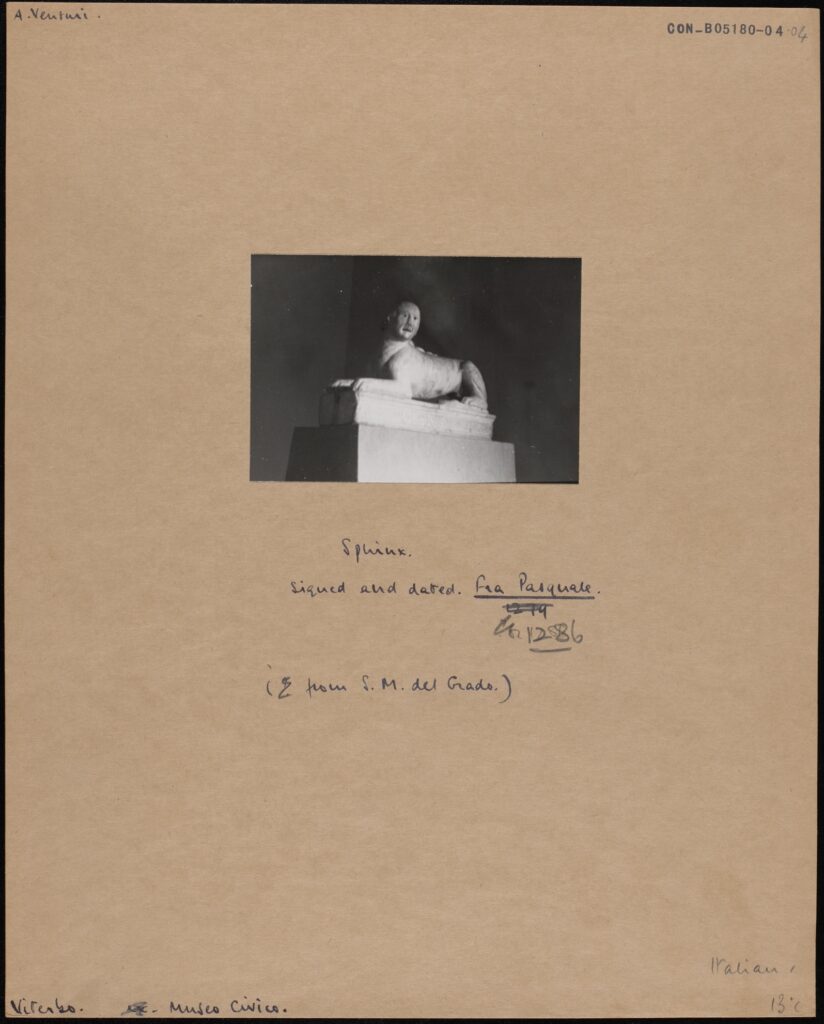

Georg Swarzenski

Swarzenski had been appointed Director General of all the museums in the city of Frankfurt-am-Main in 1928 and was responsbile for purchasing works of art from many genres, some of which were seen as ‘degenerate’ when the Nazis came to power. In 1933 he was dismissed from his posts in public office but allowed to remain as a director of a private gallery. Five years later he was arrested by the Gestapo on the grounds that he had written an anti-authority article in a local newspaper.

He was set free without charge a short while later, but being Jewish, Swarzenski realised that he had become increasingly in danger and within a few weeks he and his family had emigrated to the U.S.A. At the time of his death in 1957 he had been working as a Curator in the Medieval Arts department of Boston’s Fine Arts Museum.

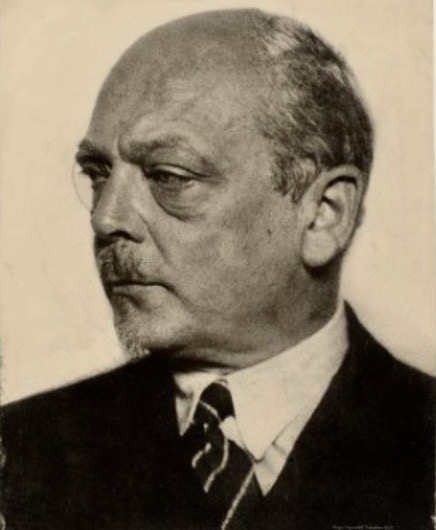

Two black and white photographs mounted on card, depicting two angles of “The Martelli David”. Burlington Magazine, April 1959. Pope Hennessy “The Martelli David” (ex Casa Martelli Florence). Washington N.G. (Widener Coll) David, ascribed to Antonio Rossellino. CON_B05578_F002_005, The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC.

Alfred Scharf

Scharf was the son of the founder of the Goldring audio equipment company and studied art history and classical archaeology in Berlin before becoming a research assistant at the Kupferstichkabinett (Museum of Prints and Drawings) part of the Berlin State Museum. As a freelance writer of art history in the early 1930’s he had planned to write a dissertation on the Italian Renaissance painter Filipo Lippi at the University of Frankfurt, but his Jewish descent and the growing anti-Semitic attitudes in the country prevented him doing so. In May 1933, he emigrated to Britain where he worked as a freelance art expert.

He also lectured on 15th century Italian and 17th century Dutch/Flemish painting at the Courtauld and was a consultant at the Warburg Institute.

Due to his considerable reputation as an art historian, in 1940 the German authorities placed Scharf on Hitler’s Sonderfahndungsliste G.B. (Special Search List. Great Britain). In the event of a successful German occupation of Britain after the retreat of British forces from Dunkirk, he would be arrested and used as an advisor on which works of art and sculptures were worthy of looting and taking back to Germany to be added to the ever growing “collections” of Hermann Göring and other prominent Nazis. Scharf’s name was one of over 2,800 on the list.

He became a British citizen in 1946 and aspects of his life and work were featured in an episode of the BBC series “Fake or Fortune”.

Ernst Nathan

A black and white photograph of Ernest Nathan/Nash. Bildarchiv, “Ernest Nash”, Goethe Universität, Frankfurt-am-Main

Nathan was born in Potsdam Germany in 1898 to a Jewish family. He studied law and Roman history in Berlin and served in the German army during WWI, where he took up photography to relieve the boredom of being stationed on the Italian Front.

After the war he resumed his studies and by 1926 had set up his own legal practice in Berlin. In the mid 1930s, the rise of the Nazis started to make life difficult for Jews like Nathan and his membership of the Communist Party added to his problems. In 1936 he and his wife and children moved to Italy but by 1938 the rise of national socialism under Mussolini meant that they were unsafe in their adopted country so they moved again – this time to New York where he set up a photographic studio.

He decided to change his name to the less Germanic Ernest Nash and over the following years established a reputation as a portrait photographer taking pictures of amongst many others – jazz musician Benny Goodman and composer Benjamin Britten who had moved to the U.S.A. as a pacifist during WWII.

After the war, Ernest resumed his studies of Roman history and architecture, moved back to Italy and devoted his life to photographing and chronicling ancient Roman and Christian sites in Italy, North Africa and the Middle East. He died in Rome in 1974.

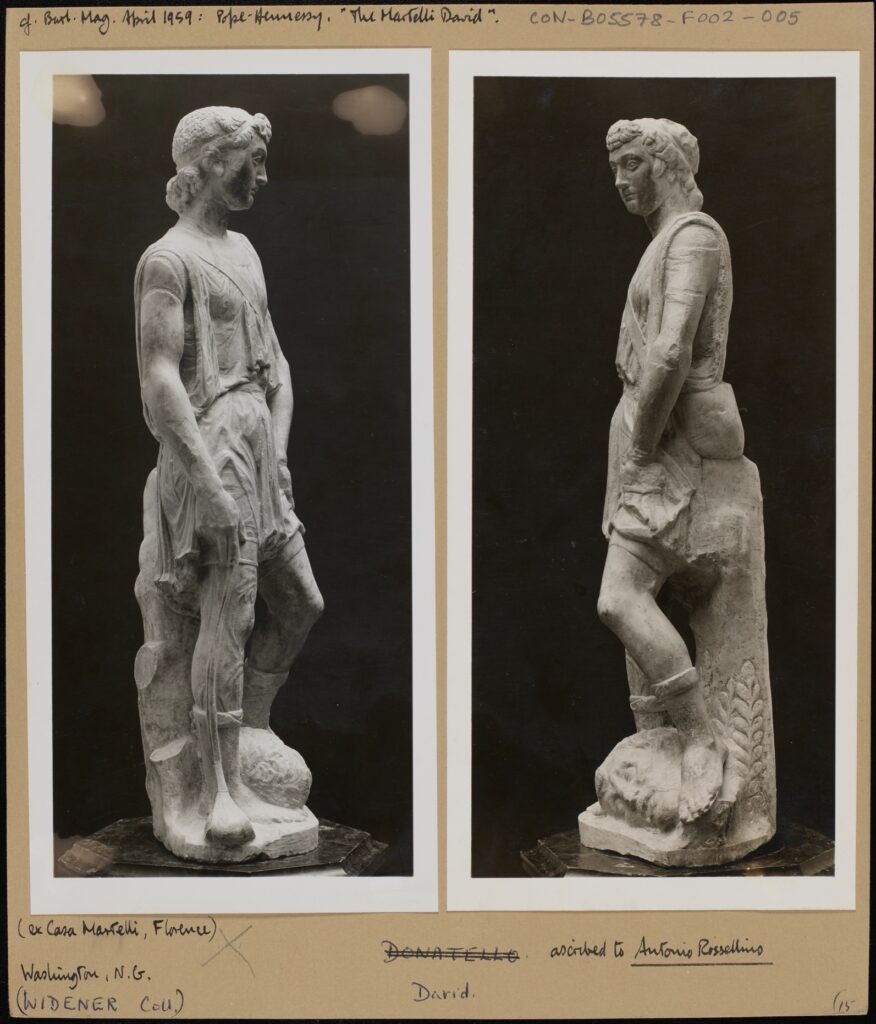

A black and white photograph mounted on card, depicting Michelangelo’s La Pietà. La Pietà. Michelangelo, Rome, St. Peters, 15th Century Italian Sculpture, CON_B05530_F001_015. The Courtauld Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-CC.

A black and white photograph mounted on card, depicting La Pietà, more specifically a detail of Jesus’ face. La Pietà Michelangelo Rome, St. Peters, 15th Century Italian Sculpture, CON_B05530_F001_035. The Courtauld Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-CC.

Susanne Lang

Lang was born in Vienna in 1907 and studied art history and ethnology at the Kunsthistorisches Institut. She graduated in 1931 and published her dissertation titled: “ Voraussetzungen und Entwicklung des Mittelalterlichen Städtebaus in Deutschland” (Determinants and Development of Medieval Urban Planning in Germany).

A black and white photograph mounted on card, depicting a stone sphinx. A. Neuturi. Sphinx signed and dated Fra. Pasquale 1286 (from S.M. del Grado) Museo Civico CON_B05180_004_004. The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

Lang was Jewish by birth and after the 1938 Anschluss when Nazi Germany annexed Austria she suffered persecution and exclusion because of her religion. She emigrated to England and formed a professional relationship with German art historian Nikolaus Pevsner. Although he had also been born Jewish, he had converted to Lutheranism at a young age, but had been forced to flee Germany due to the Nazi race laws.

They worked together on many books and during her time in London Susanne Lang worked closely with art historians and fellow academics at the Courtauld and Warburg Institutes. She retired to live in Israel and died in 1995.

So, four people whose photographs ended up in the Conway Library and whose lives were affected and changed forever by political upheaval beyond their control. There is however a twist in this story relating to another Dr whose photographs are also in the Conway Library.

Dr. Moritz Julius Binder

Binder was born in Stuttgart in 1877. He studied music at the Vienna Conservatory and then art history in Berlin.

In 1912 he became an employee of the Berlin Arsenal a Baroque style building erected in the early 18th century and which served as an armoury for the Brandenburg-Prussian Army and later as a museum.

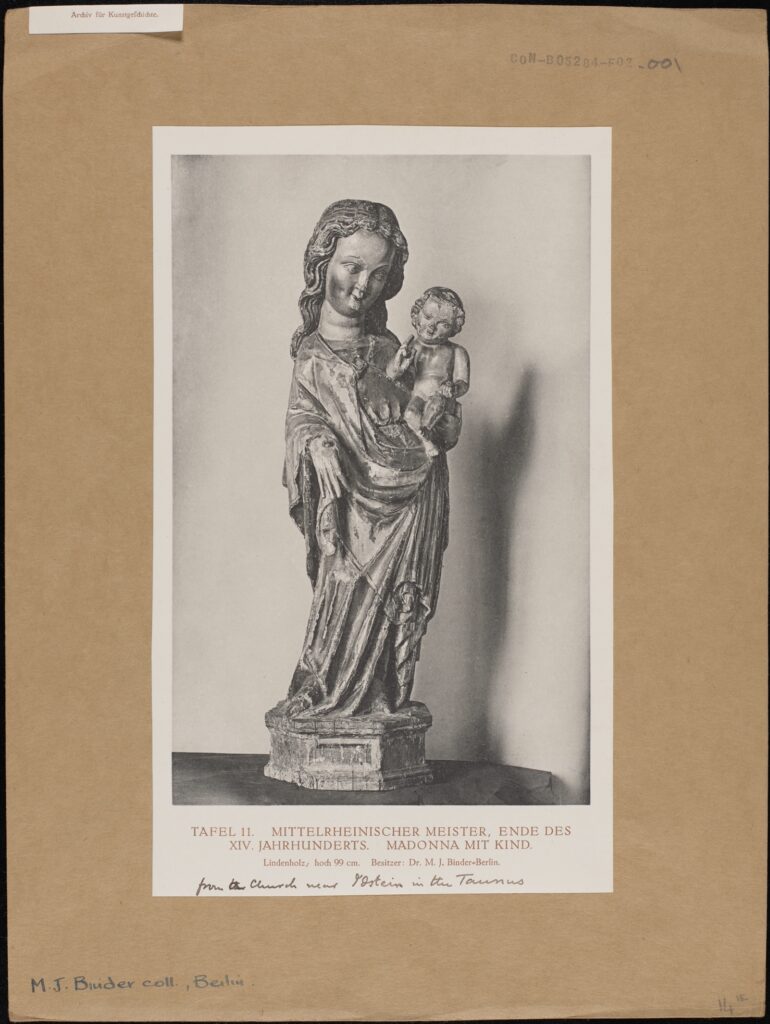

A black and white photograph mounted on card, depicting a wooden sculpture of the Madonna and Child. Tafel II MITTLERHEINISCHER-MEISTER. ENDE DES XIV JAHRHUNDERTS. MADONNA MIT KIND Lindenholz, hoch 99cm. Besitzer: Dr M.J. Binder – Berlin. from the Church near Ostein in the Taunus. MJ Binder coll, Berlin CON_B05284_F002_001 The Conway Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, CC-BY-NC

He was appointed as the Director in 1913 – a post he held for twenty years until he was dismissed under the new Nazi law aimed at ‘restoring professional civil service’ It was essentially a means of getting rid of people of Jewish or other ethic origins or those whose political views and actions were at odds with those of the National Socialists. There is no evidence that Binder was Jewish but his museum policies were criticised by far right circles, most likely due his buying and displaying what was viewed as ‘Degenerate Art”.

Reichsmarshall Hermann Göring was one of the most powerful members of Hitler’s regime and the man who instigated the policy of eliminating Jews from German economic and social life. He was also an avid ‘amateur’ art collector who became a professional looter of art from countries invaded and conquered by the Nazis before and during WWII.

During his time as a museum director, Binder had become a close friend of influential German publisher Dr Helmut Küpper and his wife, the Russian artist Paraskewe “Baika” Bereskine. “Baika” had painted the portraits of Hermann Göring’s first wife Carin who died in 1934 and his second wife Emmy and had become a favourite of the Reichsmarschall whose patronage was very useful to her.

By coincidence, Binder advised a Berlin art dealer who sold paintings to Göring. It was through this dealer Johannes Hinrichen and “Baika” Bereskine that Binder was introduced to Göring around 1935 and he is thought to have acted as a Consultant on which pieces of art were worth buying or stealing from the properties of people who had fled Germany or suffered worse fates at the hands of the regime.

In 1938 he was dismissed by Göring following disagreements about the authenticity of certain works of art and replaced by Walter Andrea Hofer. who became Director of Göring’s art collections. Hofer did not have the breadth of knowledge that his predecessor had so he often asked him for advice on what to buy or “steal”. During the war Mauritz Binder left Berlin to avoid Allied bombing raids and moved to live in the countryside. He died in January 1947.

Swarenski, Scharf, Nathan and Lang may or may not have known each other but they are all linked by their religious and cultural beliefs which brought persecution and danger to their lives. Binder on the other hand, either through choice or as an act of self preservation actively assisted the main perpetrators of their persecution by identifying works of art, some of which would have been in the private collections of Jews or Communist sympathisers which were then ‘stolen’. Most of these artworks were either not recovered or returned to their owners or families so Binder and others bore a great deal of responsibility.

Five individuals connected by chance and coincidence and thanks to the Digitisation Programme we are able to preserve some (at least) of their work and legacy where it was once at risk of being erased.

John Hurst

Digitisation Volunteer, July 2023

Why I volunteer…

Why I volunteer…