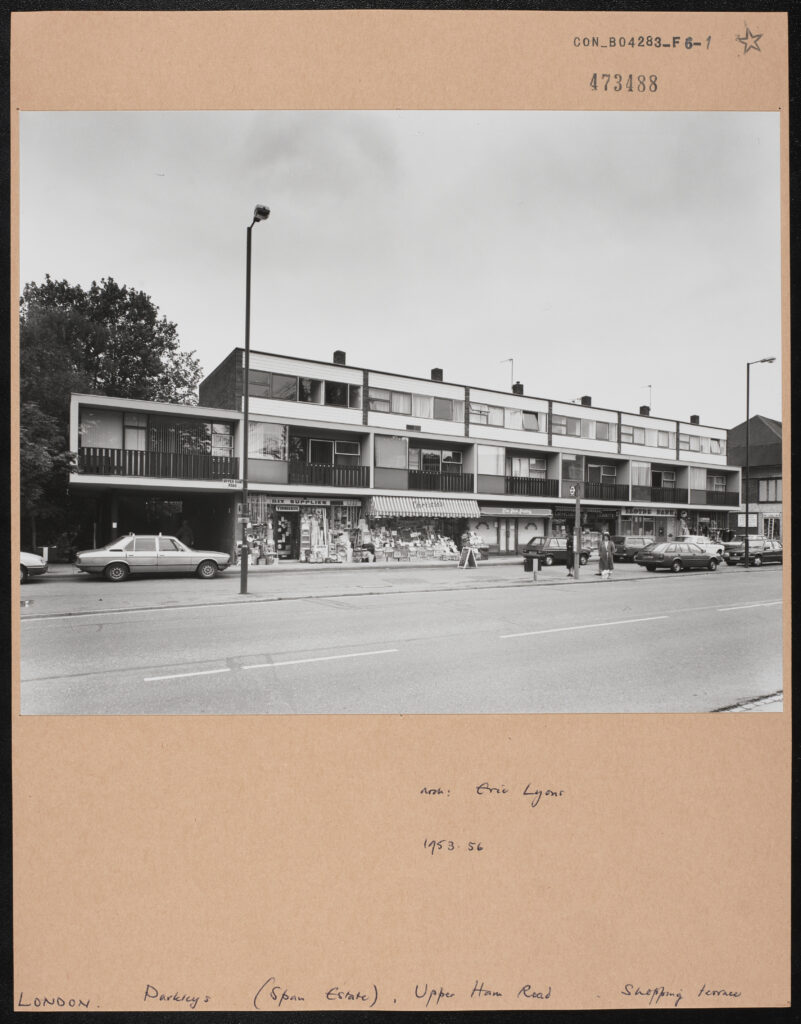

Black and white image of Parkleys Parade in 1955-56 Colour image of Parkleys Parade in 2023.

[CON_B04283_F006_001, The Parkleys Parade in Ham, pictured in 1955, Arch: Eric Lyons. 1955-56. London. Parkleys. Span Estate. Upper Ham Road. Shopping terrace, Conway Library] and in June 2023 (author’s own colour images throughout)

Community spirit lives on in post-war modernist developments

When Malcolm Singleton died in January 2022, hundreds of local residents lined the streets to applaud as he made his final journey past the shop where he had served them for more than 50 years. Malcolm was proprietor of the M&J Hardware store in the Parkleys Parade at Ham in the London borough of Richmond upon Thames, having worked for the previous owner Dorling’s since the age of 16. Richmond council went on to award Malcolm a posthumous honour for his outstanding contribution to community spirit and service to the local community.

Eric Lyons (1912-1980), architect of the Parkleys Parade and adjacent Span housing development, would certainly have approved. Lyons and architect/developer Geoffrey Townsend (1911-2002) founded Span Developments in 1957. Townsend had started his first architectural practice, Modern Homes, in Richmond in 1938. Lyons joined soon after having previously worked with Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus in Weimar, Germany, in the London practice of E Maxwell Fry.

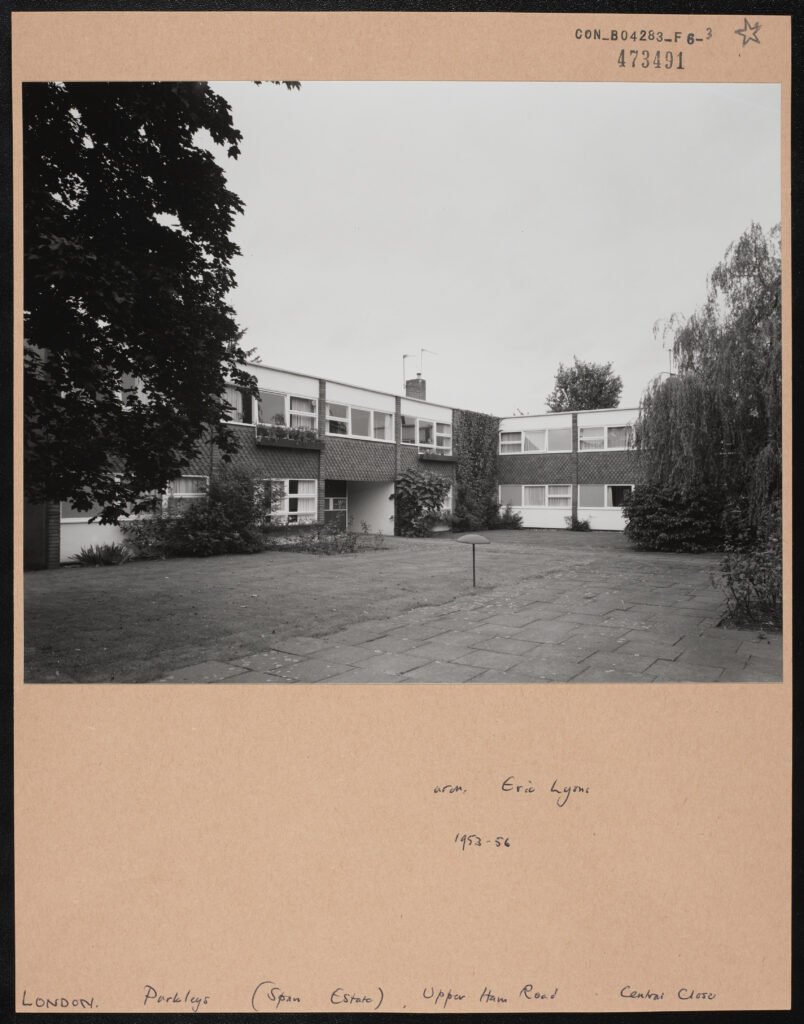

Black and white image of Central Close Parkleys in 1953-56 Colour image of Central Court Parkleys in 2023. Communal spaces are a key feature of the Parkleys scheme and look remarkably similar in 2023.

[CON_B04283_F006_003, Arch: Eric Lyons. 1955-56. London. Parkleys. Span Estate. Upper Ham Road. Central Close. Conway Library] and in June 2023.

In the 50s and 60s Span was to build more than 2,000 homes in around 70 developments in London, Surrey, Kent and East Sussex. Together, Lyons and Townsend shared a vision of social housing of modernist design in harmony with the suburban environment. Their mission was to provide affordable housing that ‘gave people a lift’ – after the Second World War, people were looking for a socially conscious society, better living conditions and a better standard of living. The architectural historian Tom Dyckhoff has said that the aim of these ‘design classics’ was to ‘span the gap between jerry-built suburbia and architect-designed pads’. He described them as sharp, modern designs with space, light and well-planned interiors, plus lavishly landscaped communal gardens designed to foster a sense of community.

A model for modern living

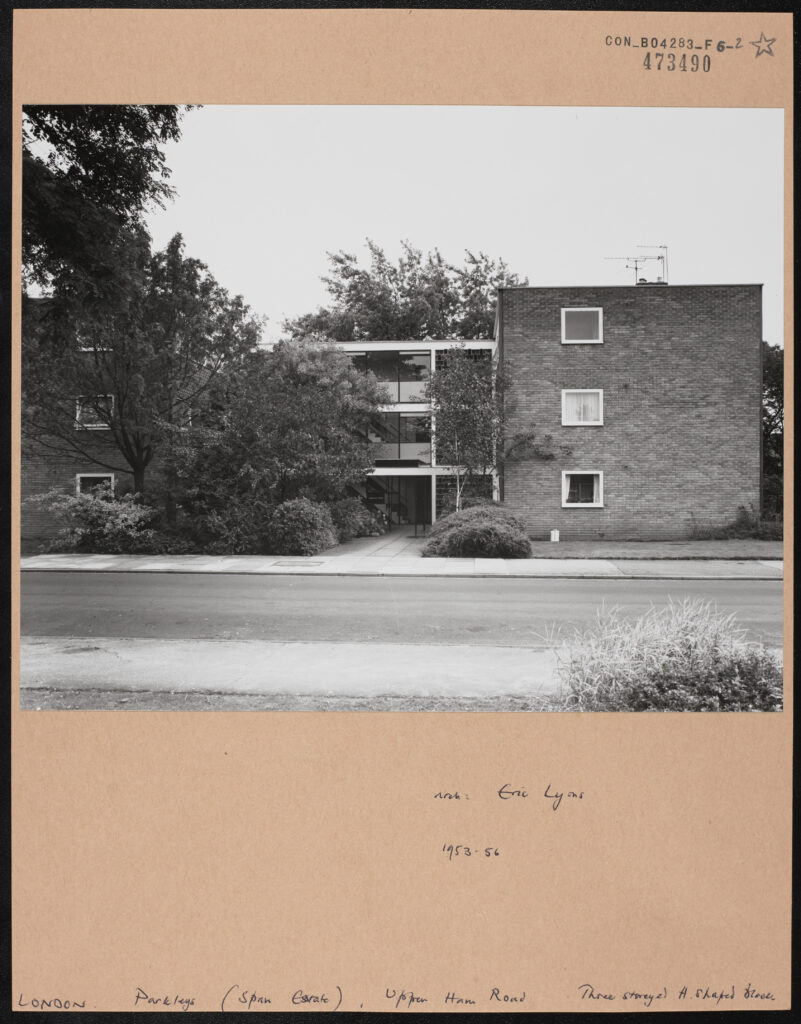

Parkleys (1954-1959) comprised 175 flats across 15 two and three-storey blocks, including garages, a garden with sculpture and the six shops and maisonettes in the Parkleys Parade on Upper Ham Road. The Span ethos was reflected in communal gardens and shared courtyards offering opportunities for social interaction, attractive public areas, car-free zones and children’s playgrounds. Residents’ societies were formed, described in the sales brochure as helping ‘to create and preserve an intelligently friendly atmosphere’. Townsend himself managed the Parkleys residents’ society until it became established.

Landscaping was considered as important as the buildings themselves, softening and obscuring the housing densities and intended to appear mature from the outset. ‘As a designer, I have always been interested in place rather than one-off buildings on isolated sites. That’s why I’m interested in landscape,’ said Lyons.

The scheme won several awards and established Span’s reputation for what today might be marketed as ‘lifestyle housing’. Parkleys was Grade II listed in 1998 by English Heritage and designated a conservation area by Richmond council in 2003.

Black and white image of Parkleys court in 1953-56 Colour image of Parkleys court in 2023. In Span developments landscaping was designed to be mature from the outset and is still an important feature today.

[CON_B04283_F006_002, London. Parkleys. Span Estate. Upper Ham Road. Three-storeyed H shaped block. Arch: Eric Lyons. 1955-56. Conway Library, Courtauld Institute of Art]

A benchmark for 20th century apartments

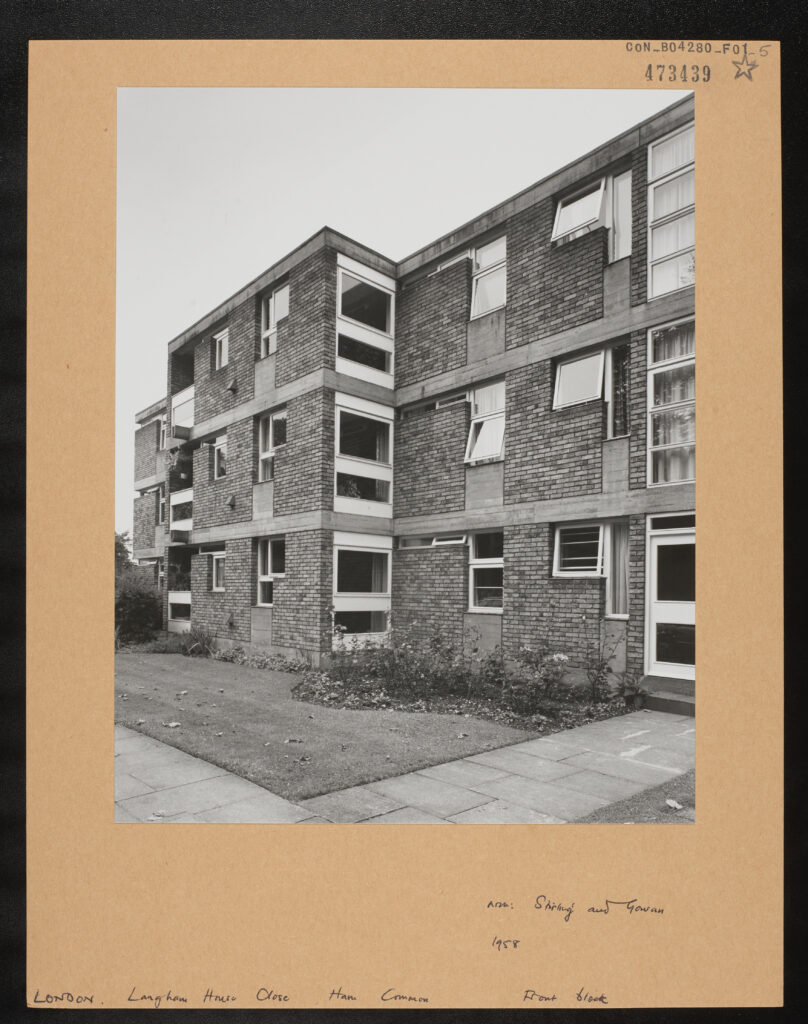

Parkleys is not the only development in Ham of architectural note and photographed for the Courtauld’s archives. 1957-58 saw the addition of the nearby Langham House Close scheme by James Stirling (1926-1992) and James Gowan (1923-2015). The buildings were the architects’ first major project together and were described by the 20th Century Society as ‘a benchmark against which all other apartment blocks can be measured’.

Black and white image of Langham House Close in 1958 Colour image of Langham House Close in 2023. Stirling and Gowan’s Grade II* listed Langham House Close, pictured in 1958 and in June 2023.

[CON_B04280_F001_005, London. Ham Common. Langham House Close. Front block). Arch: Stirling and Gowan. 1958.]

While the Parkleys scheme influenced the Langham House Close design in terms of height, construction and price, Stirling and Gowan aimed for ‘something that was just as modern but more distinctive’ and with greater innovation in the interior spaces. The brutalist design was inspired by Le Corbusier’s Maisons Jaoul (1954-1956) in the suburbs of Paris, while aiming to remain sympathetic to the adjacent Georgian building, Langham House, on Ham Common. The blocks were Grade II listed in 1998 and upgraded to Grade II* in 2006.

An enduring appeal

Today, their mid-20th century design makes flats in both developments popular purchases and they are regularly featured on property websites such as The Modern House. Both look remarkably similar to how they were pictured in the Courtauld archives in the 1950s. Their location close to Ham Common, between Richmond Park and the River Thames, has enduring appeal and the juxtaposition of mainly Georgian architecture on Ham Common makes for an interesting contrast and comparison in style. Both estates have their own official websites.

Parkleys still has a strong community feel, with its pleasant communal areas and initiatives such as the Ham Parade Market which is run by local residents. Langham House Close retains its brutalist charm. Although ‘private’ and ‘no public access’ signs make it less welcoming to non-residents or passing fans of post-war modern architecture, visits can be arranged by appointment.

The Parkleys Parade has fared less well in recent times. In mid-2023 Malcolm Singleton’s shop remained empty and there were units to let. The local council has plans to enhance the environment of the parade with wide pavements, trees and places to sit and rest.

Around the corner, the spirit of community lives on in these pioneering modernist estates, nearly 70 years since the first residents moved in.

Colour image of M&J Hardware in 2023

The M&J Hardware premises in Parkleys Parade in June 2023.

Bibliography

Eric Lyons & Span. Edited by Barbara Simms, RIBA Publishing 2017.

Let’s move to…a Span estate. Tom Dyckhoff. Guardian 26 May 2007. https://www.theguardian.com/money/2007/may/26/property.lifeandhealth

Ham Is Where The Heart Is: https://hamiswheretheheartis.com/

Parkleys Website: https://www.parkleys.co.uk/

Langham House Close website: https://www.langhamhouseclose.com/

Alison Ewbank

Digitisation Volunteer