During the first years of The Courtauld’s Digitisation Volunteer program, Peyton Cherry wrote about how the project aims to capture materiality. Cherry emphasizes how “the physical properties of a cultural artefact have consequences for how the object is used” (Lievrouw, 2014: 24–5 in Cherry, 2019). In her blog post, she discusses how the digitisation project aims to contain as much of the materiality of the photographs as possible and to preserve context. Cherry outlines how the project seeks to keep texture, marks, or stains visible in order to reproduce “the materiality of touching, flipping through the collections” (2019). When I joined the Courtauld project a few years later, I hoped to extend her ideas further and contribute to the ideas about the project itself, by highlighting that the documentation of materiality also encompasses the evidence of decades of connections between the photograph and its use.

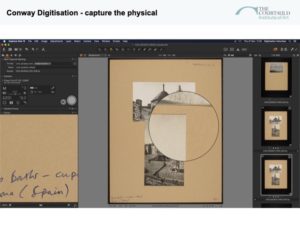

Cherry already outlined in detail the methods that The Courtauld uses for this digitisation project. The policy, with the salient points outlined below (Fig. 1), is a part of a method which ensures that the photographs and prints are not reduced to what our Head of Digital Media Tom Bilson calls “a point zero,” or a photograph contained within a timeless bubble which neglects context; Bilson’s approach to this project directly counteracts this trap in photographic theory. Again, this method is not about scanning the photograph, but photographing the photograph. In this way, the use of this object is also documented through its inclusion of handwritten notes by the photographer, labels written by curators, or numbers indicating categorization. Further, when photographing the collections for digitisation, raking light is often used to reveal a sense of depth through shadows and to illuminate small markers of use such as marks or tears. When the digitisation project includes each of these markers, the materials become signifiers of even more information, and document not just the subjects of the photographs but how everyone who has encountered that photograph has engaged with it.

Popular photographic theory follows Berger (1972) and Barthes (1977) to propose these photographs as moments frozen in time. This aligns with most reception theory, where photographs are a freeze frame fragment of time to be seen in the present. However, the methods and outcomes of this digitisation project emphasize that these are not frozen in time at all; instead these photographs are endurances which reveal our engagement with them through time. These photographs endure across time to show us that the collections refer back to themselves and to every time they have been used.

For example, the boxes containing the work of Tony Kersting boxes are labelled by his own hand, with his accompanying instructions regarding how he wishes his work to be published or cropped. Within these boxes there will also be unique identifying numbers, handwritten by volunteers, that are used to organize the collection. There may even be some small damage from an intern who was just learning how to handle museum artefacts or how to use the high-res camera. In the image below, we see that the digitised collection does not neglect to reflect on its own existence when it includes the record of its own organization and interactions (Fig. 2). Here the image contains the stories of contact between the photograph and the photographer, the individual curators, the museum structures, and the intern.

In another example, the photo below has two different styles of handwriting and a typewritten label (Fig. 3). These were likely all made at different times possibly by different people. This photograph is a part of the collection of images from the Ministry of Works documenting the damage from the bombings of WWII, with this specific photograph showing the damage to the parish church in Lambezellec, Brest. This Catholic parish still holds mass in 2021, though during the 2020 lockdown, there was an incident wherein the building was damaged again as some of the items were upturned and the lamp of the tabernacle was stolen (Ouest France 2020). Father Jean Baptiste Gless says that despite this incident, he will continue to leave the church doors open in the mornings so that people can come pray (Fig. 4).

In 2021, I came to the Courtauld project and added another tangible layer to this part of the Conway collection (Fig. 6). The layer I have added is of the undamaged church, before the bombing. Now, the image features both moments in time. This layer is not just the visible layer I superimposed but also the contribution to the knowledge around the histories of the photograph and collection. Each time we write about a photograph or engage with it in any way, we add to the histories and build upon those histories. Here, we play with time but we do not freeze it to what Tom Bilson calls “year zero.” This visual creation is especially interesting as it shows how this additive layering moves beyond the original image, stretching off the screen and reaching off the canvas.

On a theoretical level, I am also building on Cherry’s work in the same way that the collection builds on the work of hundreds of volunteers and in the same way that each engagement with the collection builds on earlier engagements. Ultimately, how the collection is digitised is not just about the photographs which end up digitised, but includes the entire history of how we have interacted with the photographs. Each engagement between curator or volunteer, writing labels or making small oily fingerprints, is a critical part of the material world created by the photograph which, through this long process of use, becomes less of an abstract digitised image and more of a museological object containing its own histories.

This project refuses to exclude evidence of its own existence. In digitisation initiatives, it is crucial to step back and look at the full scope of materiality to see how the collection is not simply materials but also the histories of how we interact with these materials. This project does that every time it records not just the numbers of archival boxes but pictures of those boxes. As Cherry (2019) suggests, the Courtauld collections are not simply photographs but cultural artefacts in and of themselves. Every picture which is not cropped, every edge revealing depth, points to the full histories of this collection and how every volunteer has become an integral part of that story.

Sydney Stewart Rose

References

Berger J (1972) Ways of Seeing. Penguin Modern Classics: London.

Barthes R (1977) The Rhetoric of the Image. In: Image, Music, Text, trans. Stephen Heath. Hill and Wang: New York.

Cherry P (2019) Journey Through Materiality – Communicating Familiarity And Distance. The Courtauld Digital Media Blog, July 1. https://sites.courtauld.ac.uk/digitalmedia/2019/07/01/peyton-cherry-journey-through-materiality-communicating-familiarity-and-distance/

“L’église Saint-Laurent dégradée à Lambézellec.” (2020, April 5) Ouest France. https://www.ouest-france.fr/bretagne/brest-29200/brest-l-eglise-saint-laurent-saccagee-lambezellec-6800809