Zaza Skhirtladze

Zaza Skhirtladze

The so-called Georgian Church is situated near to the main entrance (the Lion Gate) of the old city of Ani – on its south-west side, in the area of the ‘New City’, which is in the north-west part of the settlement. The old name of the church is lost. It is now known as the ‘Georgian Church’, due to the large number of Georgian inscriptions remaining on different sections of the building.

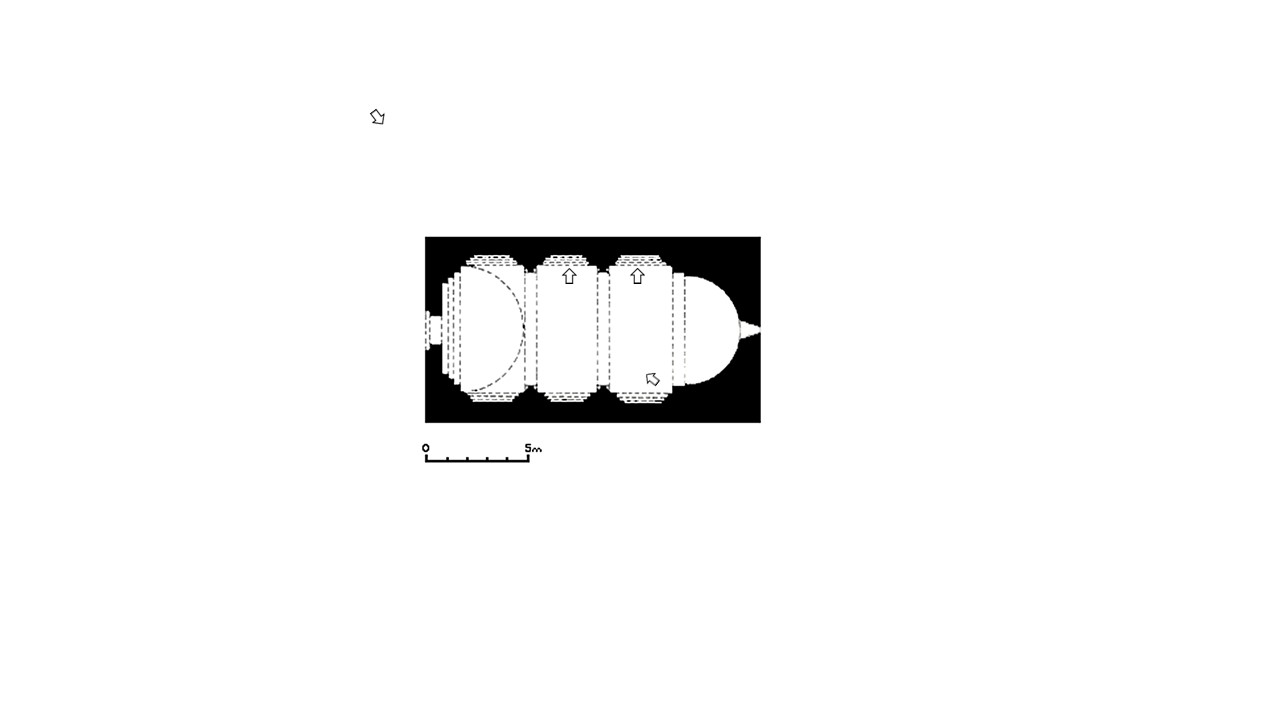

The church was a medium-sized (13.3 x 7.5 m), two-storey structure built with rose-red and well-carved tufa stones. Of the crypt on its ground floor , only the vaulted roofing remained by the early twentieth century. In old photos one can clearly see a trace of an arched structure on the west section of the south wall of the church, which perhaps served as a porch (a structure like a half-open gate) for the entrance to the crypt.

The upper church was a large, rectangular-shaped structure with a double-pitch roof. It had a single, relatively large nave ending in a semicircular apse to the east. It is likely that the only door by which to enter the church was in its west side. The internal space was divided by the arches reclining on pilasters. The side walls of the hall were decorated by semicircular blind arches (three on each wall); in the upper sections of two of them (the eastern and central ones) relief images are still preserved of the Annunciation and the Visitation. The carving style of the reliefs shows connections to the characteristic tendencies of eleventh-century Georgian reliefs/sculpture.

Only a fragmentary part of the north wall of the church still remains, erected with the piles of stones dispersed around; the wall was partly fixed with metal constructions in the 2010s by Turkish restorers.

The walls of the church were covered by Georgian carved inscriptions. They were first surveyed and studied by Nicholas Marr during the archaeological excavations led by him in the settlement. Today the inscriptions are only known through old photos and publications.

One of the inscriptions dating back to 1218 – a twenty line epigraphic document by Epiphane, the Catholicos of Georgia – was placed on the west section of the southern wall of the church. The inscription was placed on more than fifty facing stones. Nineteen lines of the inscription were in Georgian Asomtavruli whereas the twentieth line was in Armenian Erkatagir. During the excavations lead by Marr the stones with the inscriptions were moved to the storage building specially designed for archaeological discoveries, where they got lost during World War I (it is supposed that the museum staff buried the stones with other exhibits of the museum to save them during the war). In this regard, it is noteworthy that a few fragments of the inscription were found incorporated into the walls of the houses in the Ocakli village situated near the city of Ani. It seems that after the war the locals took the stones and used them to build their houses.

An epigraphic document of twenty three lines written in the Asomtaruli of Paron Sahmadan, dating back to 1288, was carved on the south wall as well. The inscription was already quite damaged by the time of the archaeological excavations led by Marr. The stones with inscriptions are in ruins nowadays. The photographic negative depicting the inscriptions from the 1910s is preserved in the photo-archive of the Art Museum, the Georgian National Museum.

Georgian inscriptions still remain in the interior of the church by the relief figures placed on the north wall, executed with white paint.

The date of construction of the Georgian Church is unknown. Based on historical context, along with the architecture of the structure and the artistic characteristics of its reliefs, it could be attributed to the mid-eleventh century. It is also possible that the church served as a seat of Ani’s Georgian Bishop for at certain times. It is also suggested that the date of the construction of the church might be connected to the donor activities of Queen Mariam, the daughter of Senakerim Artsruni, the king of Vaspurakan (1003-1021) and the mother of Bagrat IV, the king of Georgia (1027-1072) and that the church could have served as her personal crypt/burial site.

Interactive Plan