Ioanna Rapti

On the western border of the today’s Republic of Armenia, the site of Marmashen embodies the prestige of the medieval Bagratid kingdom of Ani carried through the centuries. Heavily damaged several times, most recently by the earthquake in 1986, the complex is worth noting for the respectful and responsible restoration by the Centro di Studi e Documentazione della Cultura Armena of Milano. Beyond its interest as a genuine monastic and rural landscape, Marmashen is important for its close connections with the city of Ani in terms of architecture and patronage. Marmashen significantly parallels the twofold development of the Armenian capital in the tenth and eleventh centuries and in the early thirteenth century.

Since the nineteenth century, Marmashen’s ruins attracted the attention of travellers and historians who recorded the popular explanation of the site’s unusual name as a derivative of the word for marble, although only the local ochre-orange tufa is used. The mention of Marmashen by Mxit’ar Ayrivanec’i, Samuel Anec‘i and Step‘anos Taronec‘i, all three writing in the eighties of the tenth century but from different perspectives, indicates its dynastic and political significance. This is further confirmed by the founder’s inscription which records in an elegant and careful script the completion of the main church the year 1029. Displayed as a legal document within the central blind arcade of the southern façade, this text yields the economic background of the monastery and its vocation to be a place of memory for the founder’s family. The re-foundation inscription carved on the northern façade records the restauration of the same main church in 1225 by Grigor and Gharib Magistros under the rule of atabeg Ivane and their project to recover the original splendour of the monastery and perpetuate ancestral memory.

At 35km north-east from Ani, Marmashen lies on the left bank of the Akhurian river, in the historical province of Shirak near the modern city of Gumri (Soviet Leninakan and former Alexandropol). The nearby village of Vahramaberd (2km to the north of the monastery) echoes the memory of Marmashen’s founder Vahram Pahlawuni and suggests the connection of the monastery with a fortified place, perhaps built on an ancient Urartean one. The location of the monastery overlooking a curve of the river interestingly recalls the location of Ani on the South on the other bank of the river. The water provides both connection and protection to the site which is further delimited by low hills to the south and east. The core of the monastic complex dominates a low river-level plateau. The orchards in its immediate surroundings to the South have perhaps grown in recent times[1] and do not seem to step on buildings while a ruined church and abundant fragments of tombstones suggest the existence of a cemetery to the north. It is uncertain when the monastery was surrounded by an enclosure which is visible in photographs of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

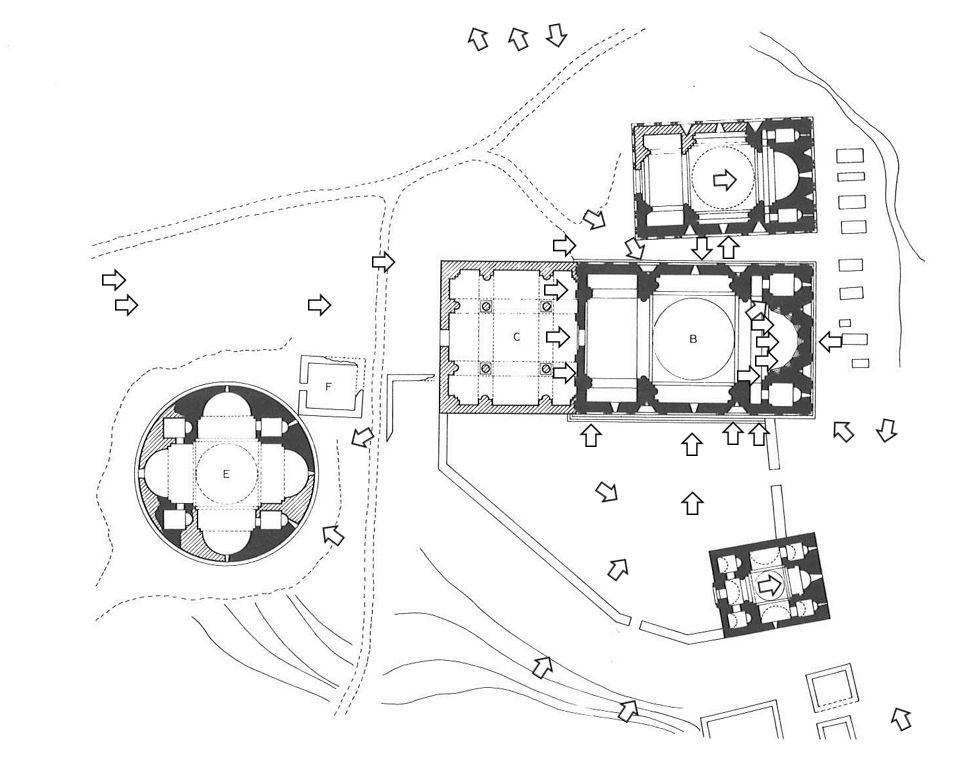

The complex comprises five churches located close to each other with the main church rising in the middle of the compound. The south church is a small cross-in-square building with plain façades and without exterior niches, topped by a high cylindrical drum supporting a conical roof. This modest and sober building (9×7.5 m) is adorned on its western façade by a window with an elaborate frame above a modest portal. On the northern wall, a second door faces the southern façade of the main church. This small south church, perhaps a chapel, may be identified with the church to which Samuel of Ani refers (between 986 and 994).

The Katholike was completed in 1029, since the inscription recording the building campaign and the endowment of the foundation must have been engraved to celebrate the consecration of the building. The inscription mentions that the work began in 986, but it is difficult to establish from where the complex started. The church stands on a stepped podium. The plan is a combination of a cross-in-square with the type of “domed hall” used in earlier periods (20x13m). The cupola and the drum sit on spandrels and their weight is divided among four arches stepping on the walls. The drum is cylindrical inside and 12-sided on its exterior: this is the umbrella-type cupola which occurs in the contemporary monastic church of Xckonk‘ and in the castle church of Amberd, built by the same founder. Inside the church, a spacious hall is dominated by the dome; a series of large arches and vaults shape the walls and lead towards the focal point of the sanctuary. This is a raised semi-circular apse accessible by two lateral stairs, perhaps repaired in the thirteenth century. On either side, two small chambers are connected to the hall by narrow vaulted passages. Throughout its lower zone, the curve of the apse is adorned by a series of elaborate double niches similar to those encountered in the cathedral of Ani.[2]

On the exterior, angular blind niches break the mass of the northern, southern and eastern sides and contribute to the elegance of the overall effect. Alongside with the fine blind arcades which harmoniously rule the façades, these are typical features of the Ani area. These arches are larger above the niches and highlighted above the central windows. Marks of a building adjacent to the western façade and the ruins on the ground betray the presence of a jamatoun (type A1), built or rebuilt in the thirteenth century. This likely housed the burial of the founder Vahram Pahlawuni.[3]

Very close to the northern side of the Kathoghike, a second church from the same period seems to replicate the main building in a smaller scale in terms of planning and decoration and with a simpler effect regarding the cupola. It has a simple cylindrical drum with a conical roof and similar decoration with blind arches, foliage, and interlaced patterns. A few meters west lay the remains of a fourth church, a rotunda, standing on a podium and encompassing four-apses around a central square and four smaller chapels radiating between them. A similar building is attested at the south-west of the Roman temple at Garni, while a rotunda raised on a pedestal with abundant mouldings is encountered at Xckonk‘ in a similarly short distance of the other buildings of complex. At the north-east edge of this church the ruins still visible are considered to belong to a burial chapel sometimes identified as mausoleum. Further north, the ruins of a small chapel indicate a free standing cross plan, likely contemporary to the complex.

The prominently inscribed dedication on the southern wall of the main church relates the complex to one of the most important and powerful families of the Bagratid kingdom. The Pahlawunis claimed their origins back to the Arsacid lineage of Saint Gregory the Illuminator and provided a series of archbishops and patriarchs. They survived the fall of the kingdom of Ani and developed into different branches through marriage to the ruling elites.[4] In 994 the founder’s father, Grigor-Abughamr, marked the fabric of Ani by a church known after his name and dedicated to Saint-Gregory (Abughamr) overlooking the bathhouse and the ravine at the west side of the city. The construction of Marmashen, intended to house the burial of the founder and his relatives, may be read as a break with the capital and at the same time an extension of the donor’s power and landholdings to the north of Ani. The fortress of Amberd, among the few surviving Armenian castles and another major landmark ascribed to the same Vahram Pahlawuni, indicates how the prince visualized his authority. This is also apparent in the endowments of Marmashen as numbered in the inscription: the monastery is given the houses and household of the donor’s family in the city of Ani, lands in several locations along the river leading to Mren, the cradle of the family, and eastwards to Ashatarak and Oshakan, in the vicinity of Amberd. The list of the properties bequeathed to Marmashen opens with Bagaran. For a short while a capital of the Bagratid kingdom in the second half of the ninth century, Bagaran lies in the lands of the Pahalwuni’s ancestors and thus enhances the endowment as a symbolic transfer of power. However, Pahlawuni donations are not limited to these new strongholds. They continue sponsoring at Ani, since in the early 1030s Vahram also gives two shops to his father’s foundation (St. Gregory Abughamenc) and in 1031 Vahram’s son donates the district of Karnut to the church of the Holy Apostles Ani.[5]

Although Armenian sources emphasize the importance of burial ad patres, memorials and funerary commissions indicate a dynamic geography of memory and ancestry.[6] Commemoration is not related exclusively to the burial but can occur separately and in different locations. In 1040, Vahram’s brother, the marzpan Prince Aplgharib Pahlawuni, built the church of the Savior at Ani located counter-symmetrically to his father’s church at the east end of the city. Although the church was not intended to house his grave, it was another statement of power with a dynastic dimension, impacting on the topography of the city. Marmashen’s distance from the city echoes a pattern of memorial patronage also expressed at Horomos and Sanahin, but also in other places and in later times. The burial inscriptions do not provide a clear evidence about the community of the dead housed there. The earliest tomb known only from the records dates to 1015 and belongs to Sophia, the founder’s wife. The connection of this grave and the ruined free-standing cross chapel is tempting but conjectural. A cross dating to 1021 gives the name of Matane who erected it, while the same year Vasak, Vahram’s elder brother was killed in battle. Except for the graves, the family, dead and alive, had a vibrant presence through the regular commemorations stipulated by inscriptions: six forty-day periods (Karasunk‘) equal almost the entire year except for the major feasts and the fasting before Christmas and Easter.[7] The later inscription, similarly establishes perpetual, daily commemoration.

Expanding the family’s geographical network with a place of memory patterned after the royal memorial monasteries, Vahram’s foundation at Marmashen is a statement of power in dialogue with the capital and its artistic traditions.

The second chronological inscription on the western part of the southern wall sheds some different light on the history of the monastery:[8] it records the donation of a village by Mariam, queen of the Abhazians and the Armenians, to the church of Saint Peter for the commemoration of her grand-mother. Mariam was the first wife of Georgi, king of Abhazia, Kartli and Kakheti, from the Iberian branch of the Bagratids (1014-1027) and regent of the future Bagrat IV (1037-1072). The citizens of Ani sought her protection after the death of Yovahnnes Smbat in 1040. On the eve of annexation of Ani to Byzantium and while imperial pressure on the Eastern frontier was increasing, the Georgian-Armenian Bagratid endowment of Marmashen may be understood as a measure to strengthen Ani through the control of a strategic spot on the Axurian.

The strategic location of Marmashen on the fluvial way to Ani was also crucial for its later life in the thirteenth century. The long inscription on the northern wall of the main church bridges the gap between two centuries and claims the Pahlawuni connection of the site. The re-founders state their will to recover the original purity and glory of the ancestral building that was squatted by villagers who turned it into a kind of fortress. They explicitly refer to the inscription of Vahram and some of the lands offered to the renewed monastery, said to be family inheritance.[9] More interestingly however, the Pahlavid branch of the new patrons has merged with the ruling family of the Mkhargrdzeli, referred to in the mention of the atabeg Ivane at the very beginning of the inscription.

Unlike other monastic mausolea founded in the Bagratid period and occupied eventually by Armenian aristocracy, such as Haghpat and Sanahin or Horomos, which developed from an aristocratic memorial to an economic institution, Marmashen, almost surprisingly, does not seem to have attracted numerous later burials and related donations (unless we accept they disappeared or were buried with the gavit).

The elegance of the structure at Marmashen and the ornamentation of the buildings, particularly of the Katholike, have legitimately allowed to ascribe the complex to the “school of Ani” and to the quasi-mythical figure of the architect Tiridate. The kinship between the Marmashen Kathoghike and the homonymous cathedral at Ani resides in the umbrella shape of the dome, the broadness of the interior, the use of decorative arches, and limited place for ornamental patterns. Recent scholarship has suggested a conscious appropriation of the Roman-classical architectural tradition and explained the 12-faceted dome as the projection of the proportions of late antique buildings.[10] Common trends also occur at Xcknonk‘ and Bagnayr closer to Ani and, at some point, in the main churches of the monasteries of Sanahin and Haghpat. The fact that none of the buildings underwent heavy restorations to update them according to the mainstream decorative patterns but instead kept close to all its central medieval parallels may point towards both a sense of “classicism” and a venerable memory of the holdings.[11]

Standard plans such as the cross in square, the radiating apses within a rotunda, and the domed hall are carefully related between them and to their natural environment. This allows variety and establishes an internal hierarchy which raises the question whether a specific liturgical ceremonial, a use of Ani may have underpinned such a pattern of aristocratic monasteries. As shapes and bearers of ornaments these standard forms do at the same time refer to the churches that defined the cityscape of Ani. Marmashen can be considered as a part of the monastic shield raised around the Bagratid capital with Horomos, Bagnayr, Xcknonk‘. In the context of the early thirteenth century, inscriptions, donations and a series of manuscripts sketch a dynamic network around Ani and expanding all over Armenian lands. According to the colophon of a Gospel book written in Rome in 1239, a native or coming from Marmashen, Sargis Marmashenc’i, is the father superior of the Armenian house of the Holy See.[12] This is an important insight to the monastery’s importance at the crossroads of religious and trade roads.

[1] Lynch I, p. 131, notes the bleak surroundings of the monastery.

[2] For examples outside Ani see Cuneo 1992, p. 434.

[3] A burial identified as his is a 19th century reconstruction. The 13th c. inscription locates his grave in the church, meaning perhaps the gavit.

[4] Toumanoff, Les dynasties de la Caucasie chrétienne, Rome 1990 : table A XXXII, p. 517 ; for the various branches and marriages see tables 53-64. A Pahlawuni branch merges with Mkhargrdzeli is attested until the 19th c.; Toumanoff, Studies in Christian Caucasian History, Washington 1963, p. 206-207.

[5] K. J. Basmadjian, Les inscriptions arméniennes d’Ani, de Bagnair et de Marmashen, Paris 1931, nos 10 and 11.

[6] A. Manuk-Khaloyan, In the Cemetery of their ancestors, REArm 35, 2013, p. 131-202.

[7] Mahé, in Horomos, p. 375, p. 402 no 4

[8] Lynch p. 132 notes an inscription inserted on the west (south-west) with the date 1021.

[9] Azata already mentioned in the first inscription, Mermet, and a church of Saint Stepanos in the city.

[10] A. Khazarian, Marmashen, Cahiers archéologiques 57, 2016-2017 (sous presse).

[11] Cuneo 1992, p. 436 privileges continuity than imitation and observes that kinship between the Ani cathedral and Marmashen may reside on their 13th c. restorations.

[12] A. Mat’evosyan, Colophons of the 13th century, Erevan 1984, no 172, p. 216-217.

Interactive Plan

Image Gallery

Bibliography

- Alishan, G. Širak. Tełagrut‛iwn patkerac‛oyc‛ (Shirak. Illustrated Topographical Study) (Venice, 1881), 147-154.

- Balasanyan, H. ‘Marmašeni čartarapetakan hamalirǝ ew vimagrerǝ’ (‘The Architectural Complex of Marmashen and Its Inscriptions’), Etchmiadzin monthly 6-7 (2008), 118-126.

- Balasanyan, H. ‘Vahramaberdǝ orpes Marmašen k‛ałak‛i miǰnaberd’ (‘Vahramaberd as Citadel of the City of Marmashen’), Kantegh 3 (2008), 154-159.

- Cuneo, P. ‘L’architecture monumentale du Chirac’, Archéologia 126 (January, 1979), 34-41.

- Donabédian, P. ‘The Architect Trdat’, Ani. World Architectural Heritage of a Medieval Armenian Capital, P. Cowe, ed. (Virginia, 2001), 53.

- Eghiazaryan, H. ‘Marmašeni vankǝ ew nra vimagrut‛iwnnerǝ’, (‘Marmashen Monastery and Its Inscriptions’), Etchmiadzin monthly 5 (1957), 35-43.

- Harutyunyan, S. ‘Vahramaberd-Marmašen-Tirašeni patmut‛iwnic‛’ (‘From the History of Vahramaberd-Marmashen-Tirashen’), Patmabanasirakan handes (Historical-Philological Journal) 3 (2008), 110-120.

- Matevosyan, K. ‘Samvel Anec‛in ew nra šarunakołnerǝ mi k‛ani vank‛eri kaṙuc‛man masin’ (‘Samuel Aneci and His Continuators about the Construction of Some Monasteries’), Etchmiadzin monthly 2 (2012), 14-16.

- Mxit‛arean, A. Tełagrut‛iwn Marmašinoy vanac‛n i Širak (Topography of Marmashen Churches in Shirak) (Vałaršapat, 1870).

- Saghumyan, S. Marmašeni vank‛ǝ (Marmashen Monastery) (Vagharshapat, 1998).

Inscriptions

- Alishan, G. Širak. Tełagrut‛iwn patkerac‛oyc‛ (Shirak. Illustrated Topographical Study) (Venice, 1881), 148-151.

- Basmadjian, K. ‘Les inscriptions arméniennes d’Ani, de Bagnair et de Marmachên’, Revue de l’Orient Chrétien 7:27 (1929-1930), 233-251 (reprinted with the same title: Paris 1931).

- Eghiazaryan, H. ‘Marmašeni vankǝ ew nra vimagrut‛iwnnerǝ’ (‘Marmashen Monastery and Its Inscriptions’), Etchmiadzin monthly 5 (1957), 41-43.

- Orbeli, H., Надписи Мармашена (Inscriptions of Marmashen), Orbeli I.A. Selected Works (Yerevan, 1963), 440-450 (first published under the same title in series Armenian Epigraphic Monuments 1, Petrograd 1914).

- Orbeli, H. Corpus Inscriptionum Armenicarum, Volume I. Ani City (Yerevan, 1966), 17, pl. V.

External links

http://www.virtualani.org/marmashen/index.htm

For old pictures, see Rensselaer Digital Collections (taken from: Parsegian, V. L. Armenian Architecture [microfilm]: a documented photo-archival collection on microfiche for the study of Armenian architecture of Transcaucasia and the Near- and Middle-East, from the medieval period onwards, with foreword by André Grabar (Zug, 1982)

http://library.rpi.edu/architecture/update.do?artcenterkey=83