Oya Pancaroğlu

The church complex of Makaravank is situated on the wooded slope of Mount Paitatap, just 3km south of the village of Achajur (medieval Mahkanaberd). The buildings date from approximately the tenth century to the early thirteenth century. Although the name of the complex indicates a dedication to a Saint Macarius (possibly the fourth-century patriarch of Jerusalem who wrote a canonical letter to the Armenians), it is not entirely clear if this dedication applied to the oldest standing church at the site or perhaps to an even earlier monastic establishment that has not survived. The entire complex was surrounded by walls and is accessed by a tunnel-vaulted gate. Outside the gate at a short distance is a fountain of spring of water that may well have triggered the initial sanctification of the site. Some ruined structures within the walled site may be identified as service buildings.

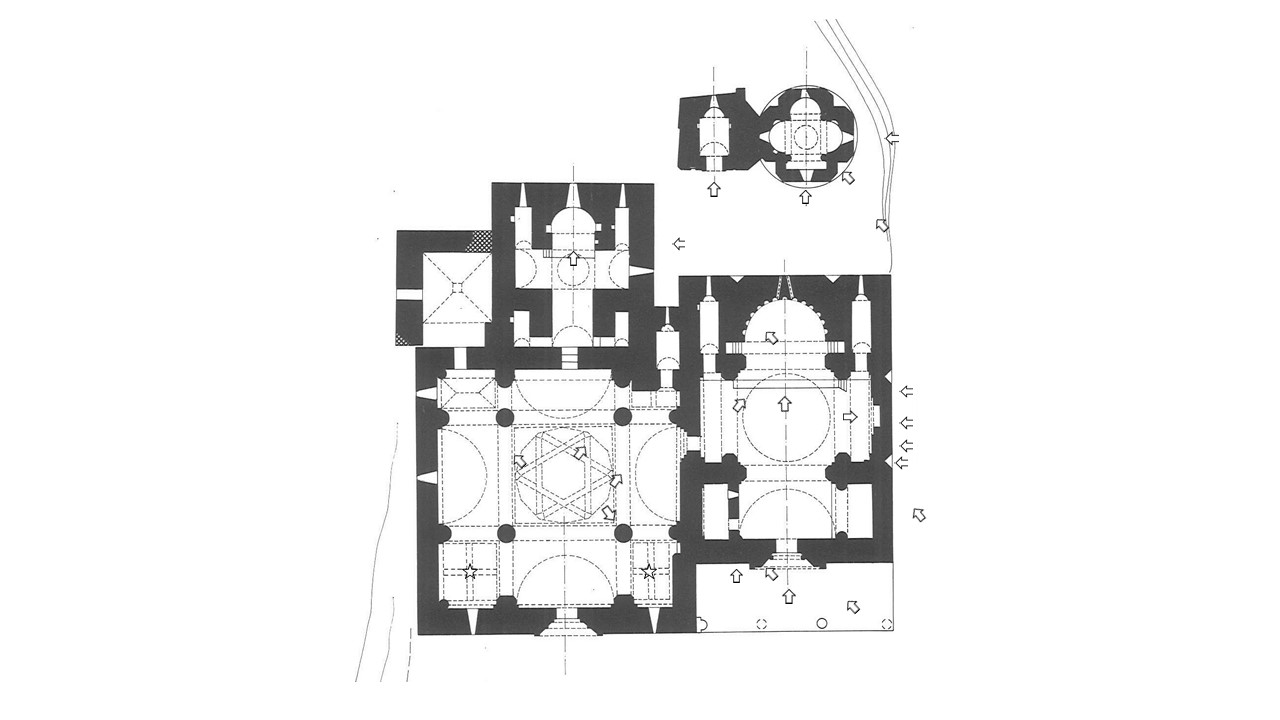

The oldest structure at the site is a small church with thick walls and an inscribed-cross plan usually dated to the tenth century. Although its original dome is not preserved, it was probably a high one, judging by the thickness of the walls. This church is preceded by and accessed from a zhamatun (or gavit) dated to the thirteenth century.

The second oldest church at the site is located diagonally to the southeast of the old church. This small octagonal church was built in 1198 and dedicated to the Holy Mother of God (Surp Astvatsatsin) by the abbot Hovhannes I in memory of his parents and brothers. Immediately to the north of this church is a small and undated chapel that is usually attributed to the twelfth or thirteenth century.

The principal church of the complex is also dedicated to Surp Astvatsatsin and is dated to 1205. Its builder is identified on a khatchkar as one Vardan, son of Prince Bazaz. This church has two entrances, one from the west side and the other from the zhamatun added later. Like the oldest church at the site, the principal church of Surp Astvatsatsin has an inscribed-cross plan topped by a high dome decorated with an arcade. Perhaps the most notable aspect of this church is the decoration of the front of the bema consisting of a rectangular panel filled with a matrix of eight-pointed stars.

The zhamatun was added to the west side of the old church no later than 1224 thanks to a donation from Prince Vache Vachutian, the main donor at Hovhannavank and Saghmosavank. It has a typical plan with four columns. Its central dome is not preserved but is presumed to have comprised six intersecting arches forming a hexagram.

******

The variety of twelfth- and thirteenth-century figural sculptures at Makaravank is perhaps the most intriguing visual aspect of this monastic complex. The exterior of the small octagonal church dated 1198 has a bird grasping a dragon-like snake above the north window; a pair of confronted lions above the south window; and a pair of bird images on its southwest façade. On the south façade of the principal church is a sculpture of a bird with prey perched atop a small structure located just beneath the rectangular window, with the head of the bird cutting into the intricately carved frame of the window. The entrance façade of the zhamatun has the most prominent paired figural sculpture placed on either side of the rectangular window above the portal frame. On the left is a lion-bull combat and on the right a sphinx moving to the left. Further to the right of this ensemble is a small window that is decorated with a pair of birds above its arch. Another window of the same size and shape is placed symmetrically to the left of the portal but it is decorated with a pair of floral rather than figural carvings. Images of paired or single birds, sphinxes, harpies as well as fish are reiterated in the interior of the principal church of Surp Astvatsatsin on the rectangular panel in front of the bema. The matrix of eight-pointed stars in two rows of twelve in this panel also include an image of a man standing in boat and another of a man coming out of the mouth of a fish, the latter undoubtedly a reference to the story of Jonah. An inscription that reads eritasard (meaning “young”) inserted as a three-line tablet to the right of the man in the boat (possibly a reference to Noah) may perhaps be the artist’s signature although this remains unverified.

These figural sculptures raise a number of issues that are not easy to resolve but that nonetheless illuminate the challenges inherent to much of medieval figural ornament, be it Armenian, Byzantine or Islamic. A chronological overview of the architecture of Makaravank opens up the question of whether these images should be considered separately from each other or collectively. Given that the construction of the structures postdating the oldest church (which appears to be devoid of any figural sculptures) is spread over the course of only about a quarter of a century (from 1198 to about 1224), it would seem reasonable to suppose a deliberate continuity starting with the small octagonal church and continuing with the principal church and finally ending with the zhamatun. That is to say, the idea of figural ornamentation apparently introduced at the site by the small octagonal church may have been intentionally picked up by the builders/patrons of the later two structures, perhaps to maintain a visual continuity between the buildings and the identities associated with them. It may also be that the continued interest in figural decoration was made possible by continuous access to the same craftsmen or workshop although evidence for this has not been put forward.

Confronted with such a configuration of figural images, it is easy to fall into the act of cherry picking those examples that seem to be more “significant” than others in terms of iconography and meaning. For example, the images identified as that of Jonah and Noah (?) on the bema decoration of the principal church draw attention to themselves on the basis of their seeming narrative connections. However, it should be noted that these two images are not visually elevated above the remaining twenty-two eight-pointed stars that contain non-human figural images and geometric and/or vegetal motifs. In fact, it would almost appear that there is no hierarchy or order to the configuration of these stars with regard to the designs contained within them. Thus, a methodological quandary emerges when the detection of specific iconography is counteracted or frustrated by what appears to be artistic ambiguity concerning the “significance” of that iconography.

A similar problem arises with the two sculptures above the entrance to the zhamatun. The lion-bull combat on the left can be “read” as an image derived from the astrological/astronomical representation of Leo and Taurus around the spring equinox. The “combat” aspect of the iconography is related to the changing visibility of these two constellations with Leo rising and Taurus descending before the spring equinox and the opposite occurring after the passing of the equinox. As a signal of the beginning of the agricultural calendar, the combat of Leo and Taurus is as much an expression of the cyclical nature of time as it is of the inevitable rotation of power. The pairing of this image with a sphinx, however, is not easily resolvable. Whether the pairing of these images had a particular meaning or not remains unanswered. Even in the possible absence of a narrative or symbolic connection between the two, it must be conceded that these images have equal visual weight, not unlike the twenty-four eight-pointed stars in the principal church.

These issues, however thorny they may be, can be embraced as an invitation to pay closer attention to the particular ways in which figural sculptures at Makaravank form part of a visual grammar. One observation is the concomitance of symmetry and asymmetry in the disposition of these images. On the small octagonal church, the image of a bird grasping a snake on the north side seems to be balanced by the two lions on the south side. However, this directional equivalence is undermined by the two bird images on the southwest side, creating an asymmetrical deployment of figural sculpture on the building. On the façade of the zhamatun, the right-side window is decorated with two birds but the left-side window has floral decoration. Inside the principal church, the altar panel is governed by the strict geometry of the matrix of eight-pointed stars, but there is no apparent symmetry, order or hierarchy with regard to the figural and non-figural motifs contained within them.

Another, perhaps not unrelated, aspect of the figural sculpture is its relationship to the architecture. Almost all of the exterior sculpture is associated with windows, being placed on top, below or beside the various window framing devices. One exception to this is the pair of bird images on the southwest façade of the small octagonal church. This relationship between figural sculpture and windows is certainly not unique to Makaravank. Nevertheless, the particularly close association between windows and figural sculpture here is especially noticeable on the south façade of the principal church where the head of the bird of prey cuts into the lower frame of the window. The fact that the bird is perched on a miniaturized architectural element further strengthens the notion that such figural sculpture should be considered in tandem with the composition of the church building.

Interactive Plan