Polina Ivanova

Çifte Minare Medrese, also known as Hatuniye Medrese, is located in central Erzurum, within the citadel walls (içkale) next to the 12th-century Ulu Camii (Great Mosque). With a perimeter of 35 x 48 m, it is the largest surviving Seljuk-era medrese in Anatolia.

The date of the construction of this monument has long been debated. According to the unconfirmed report of a local informant, cited by the nineteenth-century scholar François Alphonse Belin, the medrese at some point possessed a Persian inscription saying that it had been constructed in the year 351/962 and that its builder had come from Khwarezm and settled in Erzurum at the time of one Sultan Melik Han. According to the report, the inscription was stolen during a Russian occupation of the city. The veracity of this information has been called into question by later scholarship and various dates have been proposed, mostly placing it within the thirteenth century. Aptullah Kuran suggested that the medrese must have been built in the place of a smaller Saltukid-era building in the late thirteenth century by Hudavend Padishah Hatun, the wife of Ilkhanid prince Kaykhatu who was ruling Erzurum from 1285-1291. Other scholars, such as Michael Rogers, dated it earlier to approximately the mid-thirteenth century.

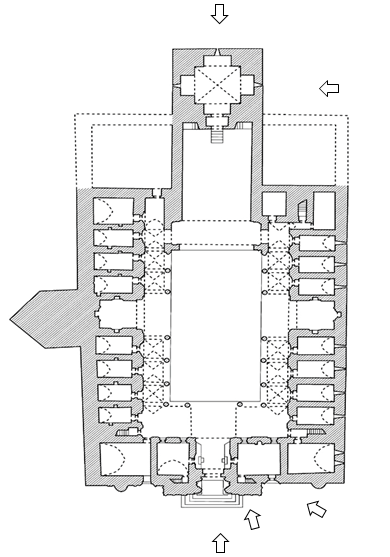

Çifte Minare medrese is a stone structure built on a four-iwan plan centred around an open courtyard. The central court measures 30.5 x 12.2 m and is framed by two-storey porticos to the east and west. Each portico has two rows of six pointed arches, the fourth arch extending over two floors and forming the entrance to the side iwans. There are eight cells on each of the floors along the east and the west walls (four on each side of the iwans, sixteen in total), connected by small internal staircases.

While the interior courtyard is perfectly rectangular, the external eastern wall diverges to the side a little, so that the cells on the southern side of the iwan are almost a metre longer than those on the northern side. Kuran suggests that this irregularity is due to the fact that the medrese was built adjacent to the citadel wall and that the building later had to be turned a little in order to observe the correct direction of the qibla.

The building is perhaps best known for its extremely ornate portal. The entrance gate is framed by a deep muqarnas niche. The niche is placed under a blind arch between two jambs framed by five rectangular bands of increasing width. The minaret pedestals are decorated on the front and sides with symmetrical relief sculptures inscribed in pointed blind arches and rectangular frames. The relief composition can possibly be interpreted as a tree of life. The tree stems from a crescent resting upon two joined chimaera tails and is formed by date leaves opening up like a fan. The relief on the front of the minaret pedestal to the right of the entrance also features a double-headed eagle. The minarets are made of brick, their surface formed by sixteen convex flutings inlaid with turquoise glazed tiles. The bases of the minarets are decorated with circular medallions inscribed in squares, similar to those on the Çifte Minare Medrese of Sivas.

A türbe (mausoleum), known as Padişah Hatun Türbesi, opens off the south side of the building. Built on a 13.5 x 13.5 m square foundation, it is considered to be the largest of medieval Anatolian mausolea. It has two floors, the lower serving as a crypt and the upper as a masjid. A door in the back of the southern iwan leads to the crypt, while the entrance to the masjid is accessed through symmetrical double-sided stairs. The türbe is a dodecahedron resting on a square foundation topped with a conical roof. Its entrance was originally framed by a portal, which no longer survives. According to local tradition, it too was taken away by the Russians. The western wall of the türbe has a narrow corridor leading outside, which allowed visitors to enter it without having to pass through the medrese. A simple sarcophagus is found in the southern wing of the upper floor today but it is considered to be a later addition; no sarcophagus is found in the crypt.

Interactive Plan

Image Gallery

Bibliography

- Belin, F. A. ‘Extrait du journal d’un voyage de Paris à Erzeroum’, Journal Asiatique 4e, série XIX (1852), 365-378, pls. I-III.

- Blessing, P. Rebuilding Anatolia after the Mongol Conquest: Islamic Architecture in the Lands of Rum, 1240-1330 (Farnham, Surrey & Burlington, VT, 2014), 123-165.

- Kuran, A. Anadolu Medreseleri, vol. 1 (Ankara, 1969), 116-123.

- Rogers, J. M. ‘The Çifte Minare Medrese at Erzurum and the Gök Medrese at Sivas: A Contribution to the History of Style in the Seljuk Architecture of 13th Century Turkey’, Anatolian Studies 15 (1965), 63-85.

- Ünal, R. H. Çifte Minareli Medrese: Erzurum (Ankara, 1989).