In the latest blog celebrating collections around the UK, Adam, Visitor Services Assistant at The Harris Museum, Art Gallery and Library, discusses three fantastic works on show in a current exhibition.

The Harris Museum and Art Gallery, Preston, has a long connection to the Courtauld Gallery, as Courtaulds Ltd. formerly had a large factory in the city. The Artful Line exhibition at The Harris is the latest fruit of this partnership, and explores the process of drawing from a variety of angles.

My choices are all from this exhibition. I have not had the opportunity to visit the Courtauld Gallery in London and view the artworks there in person, and I believe it is impossible to fully appreciate a piece of art unless you have stood in front of it. I also had to include three pieces as favourites, as they are presented as a trio in the exhibition, and their thematic links would be lost if one was sidelined.

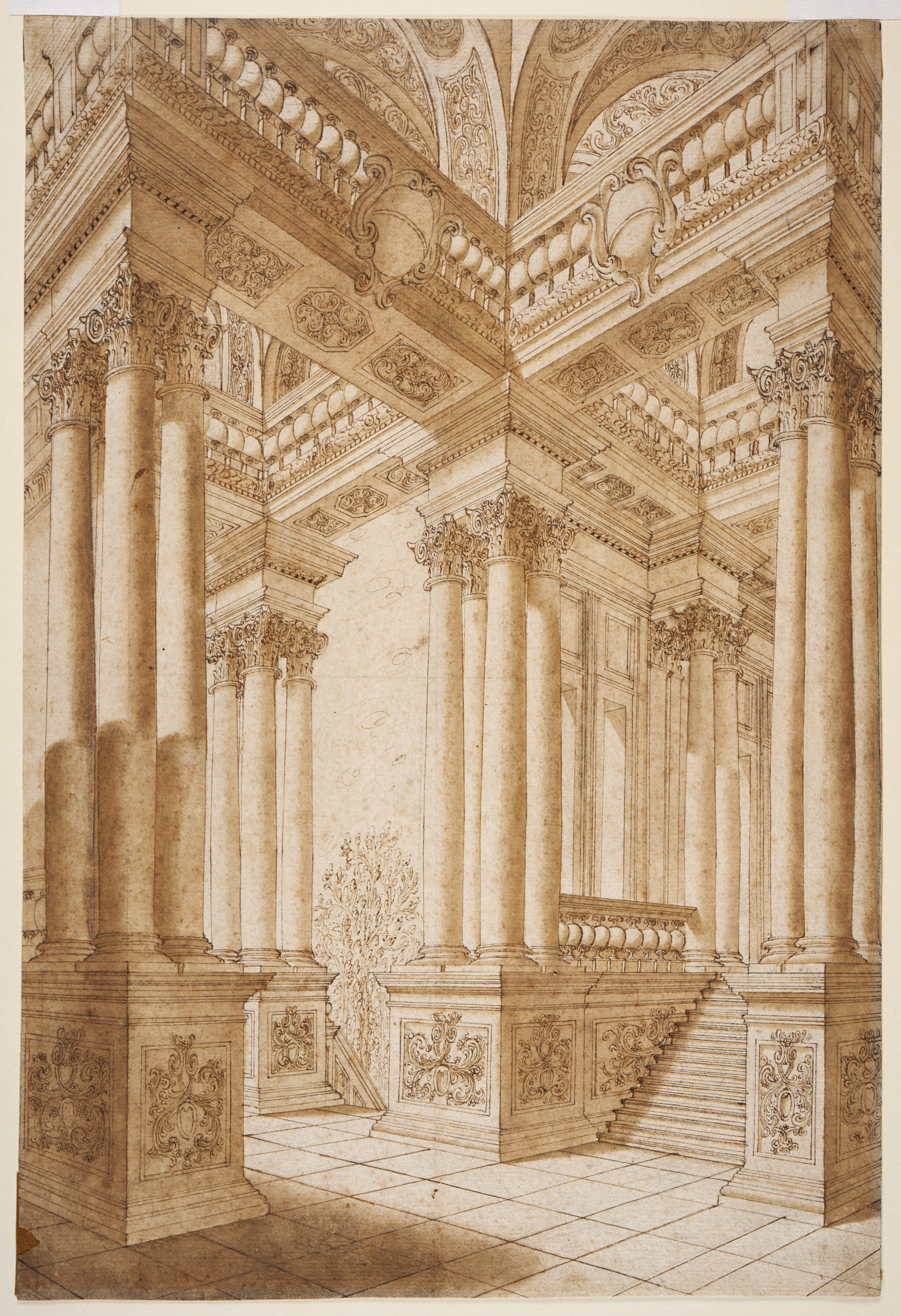

The earliest drawing of the three is Architectural Fantasy, from the school of Giuseppe Galli Bibiena, drawn in about 1740. The piece is an imaginary interior – possibly of a palace or a public building – whose architecture is extravagant to the point of absurdity. Clusters of Corinthian columns shoot upward to bulbous balustrades and Baroque cartouches, while two staircases lead to destinations unknown, but surely magnificent – a tree can be glimpsed behind one, suggesting an idyllic landscape. Yet a close inspection reveals all sorts of imperfections, from wonky urns to inconsistently-spaced flagstones. The contrast between the far view and close inspection enhances the sense that this was intended to be a whimsical drawing, more concerned with fancy than absolute precision. It is a pleasing contrast to the Harris building, which is a polished work of Victorian

neoclassicism.

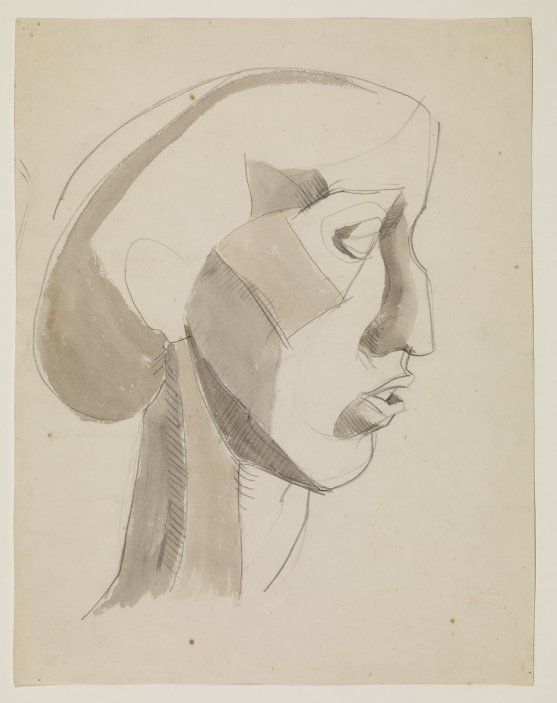

On the right of the group is Helen Saunders’ Vorticist Composition. A portrait by Saunders has already made an appearance in this series, but this piece was created at the height of the Vorticist movement. It is a small drawing, yet the confidence and boldness of its lines immediately draws the eye. The drawing has a strong sense of movement despite not being identifiable as any particular object; the influence of the Cubists is apparent, but the angularity and completely abstract nature of the piece sets it apart. A close examination

reveals that the hatching, while roughly done, is grouped into distinct blocks, giving a sense of order amid the overall disorder. I knew nothing about the Vorticists before the exhibition opened, and its inclusion has encouraged me to explore more of the works of this dynamic but brief movement.

Preliminary Sketch for ‘A Broken Set of Rules’ is the final drawing. It was created by Deanna Petherbridge as part of her 1984 commission to design the sets for the Royal Ballet production of the same name. Its large size and stark lines give it a commanding presence, but one which harmonises with the drawings that flank it. Petherbridge’s style combines the assertiveness and abstraction of the Vorticists with the keen eye for detail of the Architectural Fantasy, and the result is a disordered jumble of columns, architraves, and pediments, all jostling for position and teetering on the edge of collapse. I’m a particular fan of the semi-transparent column in the centre of the drawing, which passes through another in a way M. C. Escher would have been proud of.

When taken together, the three paintings form an interesting response to the values of classical architecture. Architectural Fantasy undermines the seriousness of classicism, related as it is to the theatrical illusion and impermanence. Broken Set of Rules takes this further, distorting the familiar elements of classical architecture and encouraging the viewer question the values such architecture often projects – power, confidence, and tradition. Finally, Vorticist Composition rejects tradition entirely, and presents a fresh way of viewing space. As The Harris itself is a classical building these responses are particularly pertinent – many recent developments in the building have focused on making its austere Victorian spaces more approachable for modern visitors, while at the same time its self-assured exterior has become an iconic feature of the Preston skyline.

Before working at The Harris I had not given much thought to the process of curating when visiting galleries, and this exhibition has given me a small insight into the work that goes into creating meaningful relationships between artworks. At first glance these drawings did not seem to have anything in common with each other, and it is only after contemplating them that I began to understand why they had been hung as they had. All

in all, I’d go so far as to say The Artful Line is the first exhibition I’ve understood, rather than simply looked at.

Find out more:

All of the works in The Artful Line exhibition are available to view in an online tour, Deanna Petherbridge talks about her work in a blog for the exhibition, and Ketty Gottardo, Martin Halusa Curator of Drawings, talks about Helen Saunders in a film for the exhibition and Open Courtauld Hour’s event about women artists.