Audio Version

Read by Anna Thompson

Text Version

The Tate Archive holds some of the only remaining correspondence between photographer Paul Laib (1869-1958) and the artists who hired him: a misaddressed cream card dated July 1935 listing his telephone number, address in London’s South Kensington borough, and services offered. All in vibrant red ink: “Carbon Platinotype, ENLARGEMENTS, &c … Pictures carefully Photographed by Panchromatic Process. PHOTOGRAVURE.” (TGA 977/1/1/222)

E.Q. Nicholson, the eventual recipient of the note, was one of many clients Laib worked with over his five-decade career as a Fine Art Photographer in London. The title listed on Paul Laib’s stationery implied a role somewhat different than the common understanding of the term today. Whereas the contemporary use most often refers to an artist whose chosen medium is photography, fine art and people who made it comprise the subject matter of nearly all 22,000 images in the De Laszlo Collection of Paul Laib Negatives at The Courtauld.

I remember the initial thrill of coming across Laib’s photographs of studios, particularly Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson’s at No. 7 The Mall in Hampstead. There is something tantalisingly subversive about seeing well-known and well-loved works of art loved and known somewhere other than a gallery, somewhere where the rules of engagement with art might be relaxed. Hepworth and Nicholson hired Laib at various points in the 1930s to photograph their work. These weren’t snapshots, though – the depiction of possibility in these photographs, of the possibility of different kinds of interactions with art, was intended. Lee Beard, Sophie Bowness, and Chris Stephens all note in the exhibition catalogue for 2015’s Barbara Hepworth: Sculpture for a Modern World that photographs like this were a concerted effort to convey a more holistic aesthetic view – if anything, one that the artists had more control over than in a gallery. Textiles, sculptures, and paintings live alongside a spiky selection of cacti, works in progress, tools, and the ephemera of a filled, well-considered space.

With some more reading, trips to archives at Tate and the National Art Library, and discussion with colleagues here, I decided to expand on the idea that placing artworks in different contexts change how we feel about perceive them. Showing how Laib’s photographs depict a range of art-in-context, and how his unique occupation brought together photography, art, and the archival in an unexpected way – became the theme of the show, now up in the Book Library Foyer until September 27.

I had never previously considered the legions of photographers capturing the artwork we see in books, exhibition catalogues, lecture halls, and postcards. This is more than a little ironic considering that I and sixty other volunteers are taking on a similar role in our time at The Courtauld.

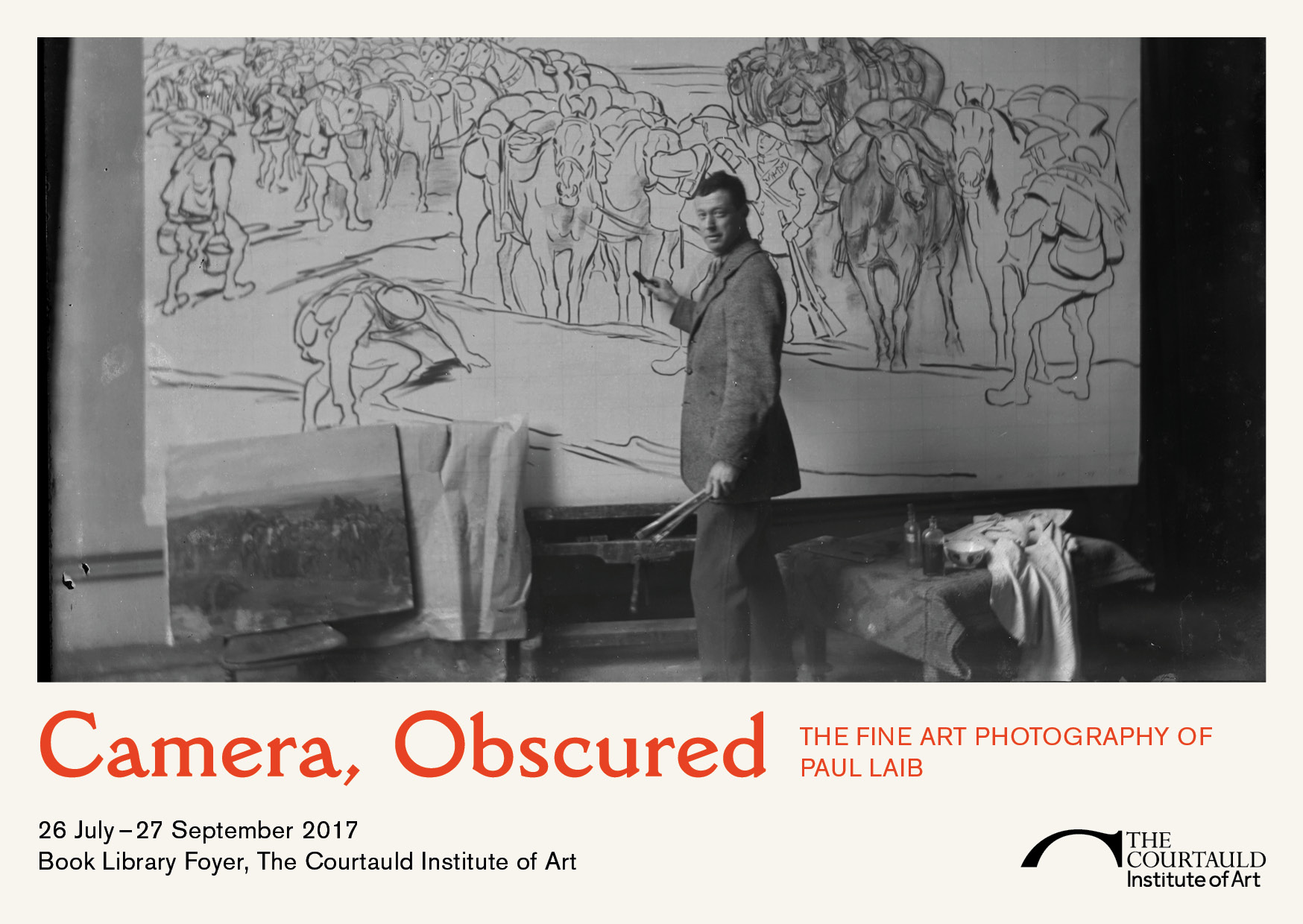

The title of the exhibition – Camera, Obscured: The Fine Art Photography of Paul Laib – is a reference to the different relationships at play between artworks and photography in his archive. As I write in the introductory text for the piece, sometimes an image itself reminds us that we’re looking at a staged photograph, something that took scheduling, supply sourcing, and time to plan. Paintings were secured on easels and sculptures on pedestals to ready them for a photo. Further reminders of the presence of the photographer include graphic white strokes across many of the images – Laib placed tape directly on the negatives to mark where the images would be cropped.

In other photographs from the archive, the physical presence of the camera is less obvious. This is particularly the case for photographic reproductions intended for publication – a copy of Art Now: An Introduction to the Theory of Modern Painting and Sculpture (1933), generously lent by the Courtauld Institute’s Book Library, is open to a photograph of Barbara Hepworth’s sculpture “Reclining Figure” – while staged in a very thought-out way, the presence of a photographer is less obvious, thus “Camera, Obscured”.

To give visitors even more of a sense of how these photographs live as physical objects before being digitised in our studio in the Witt Library and printed, some of the glass plate negatives and the boxes they have been stored in since the 1970s are included in the exhibition.

Many thanks to everyone who has helped source negatives in the archives, point me towards references, set up the show, and supported in ways large and small – hopefully this will be the first of many exhibitions to come out of the rich photo archives we are digitising.

— Mary Caple

Camera, Obscured: The Fine Art Photography of Paul Laib is on show until 27 September in the Book Library Foyer at The Courtauld Institute of Art.