Natasha Gertler guides us around the many minerals that decorate a lavish 16th century portable altar. Natasha researched and produced this project during her MSc in Science Communication at Imperial College, London.

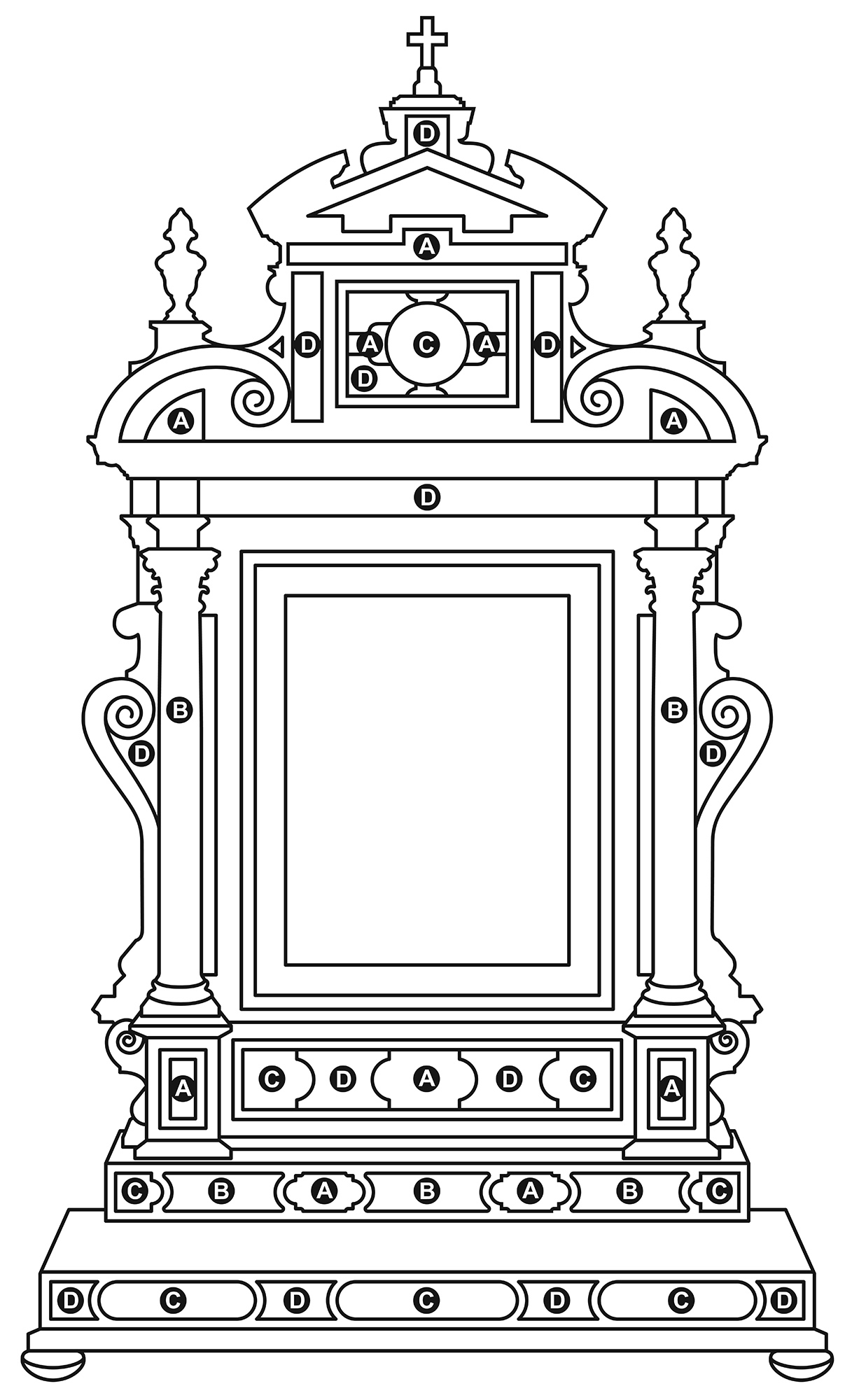

In Pieter Aertsen’s (1508–75) panel from 1530, Christ drops to his knees in agony, the weight of his cross too much to bear. When the artist painted this heart-wrenching artwork, he could hardly have known that centuries later, it would be placed in a frame that threatens to steal the show! This Roman baroque frame is a magnificent object in its own right. Here is the place to learn more about its meticulous craftsmanship and how one goes about identifying its multitude of semi-precious stones. We will discover which characteristics to look out for in lapis lazuli, amethyst, agate and Sicilian jasper.

Pietre Dure Decoration

This frame is typical of the richly decorated portable altars of the baroque period, which were commissioned by wealthy individuals for their private chapels. It was only in the late 1960s that the collector Count Antoine Seilern (1901–78) acquired it to serve as a frame for Aertsen’s double-sided painting. As well as Christ carrying the cross, the panel depicts the Annunciation. The frame is elaborately inlaid with an arrangement of coloured and patterned stones, using an Italian technique known as pietre dure. Translated as ‘hard rock’ in English, this practice originated in the 16th-century Florentine workshops of the Medici and refers to the inlaying of fitted, polished stones to create decorative compositions.

A video of the recreation of a pietre dure panel from a 17th century cabinet can be seen here:

[Video courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum. View on YouTube]Pietre dure is the beautiful result of the interplay of man and nature. Through cutting, polishing and delicate arrangement, the true beauty of nature’s wonders are revealed. Sometimes even coloured materials were placed behind translucent stones in order to enhance their sheen. This is probably the case for the lower wine-coloured band, where amethyst, a translucent mineral, seems to have been backed with a red material, producing a reddish-orange glow when illuminated:

At first, we thought that this backing could be a red metallic foil but it is in fact more likely to be a red resin, based on the very recent discovery of resin behind some of the amethyst pieces in the J. Paul Getty Museum’s extraordinary Borghese-Windsor cabinet, as shown below:

The Borghese-Windsor Cabinet goes on view today at the Getty Center. Anne-Lise Desmas, curator and department head sculpture and decorative arts, invites you to take a closer look at this magnificent work of furniture, sculpture and stone inlay (pietre dure) made in Rome about 1620 for Pope Paul V and later acquired by King George IV of England. The cabinet is now on view in the East pavilion at the Getty Center. Learn more about this important acquisition and plan your visit: http://bit.ly/2s4LLgV

Posted by Getty on Tuesday, June 13, 2017

Of striking resemblance to the Courtauld’s frame, in both their design and arrangement of the stones, are two portable altars of similar sizes in the collections of the Palazzo Pallavicini in Rome and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London (V&A). All of these frames are made in Rome and dated to the first half of the 17th century. Despite differences in their details, and the more elaborate decoration and richer appearance of the Pallavicini example, the pietre dure inlays are very similar. We can see a prominent use of lapis lazuli, amethyst, agate and some of the same varieties of Sicilian jaspers. It is intriguing to note that both the V&A and the Courtauld frames seem to exhibit the same amethyst inlay probably backed with a red substance (resin?), as mentioned above.

Rome, first half of the 17th century, ebony with pietre dure decoration of lapis lazuli, amethyst, agate and Sicilian jasper, 62 x 35 x 9 cm, Adoration of the Magi below two putti, oil on amethyst, Palazzo Pallavicini, Rome

Rome, first half of the 17th century, ebony with pietre dure decoration of lapis lazuli, amethyst, agate, Sicilian jasper and tortoiseshell, 50 x 31 x 7 cm, The Flight into Egypt, oil on lapis lazuli, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 1556-1856

Rocks and Minerals

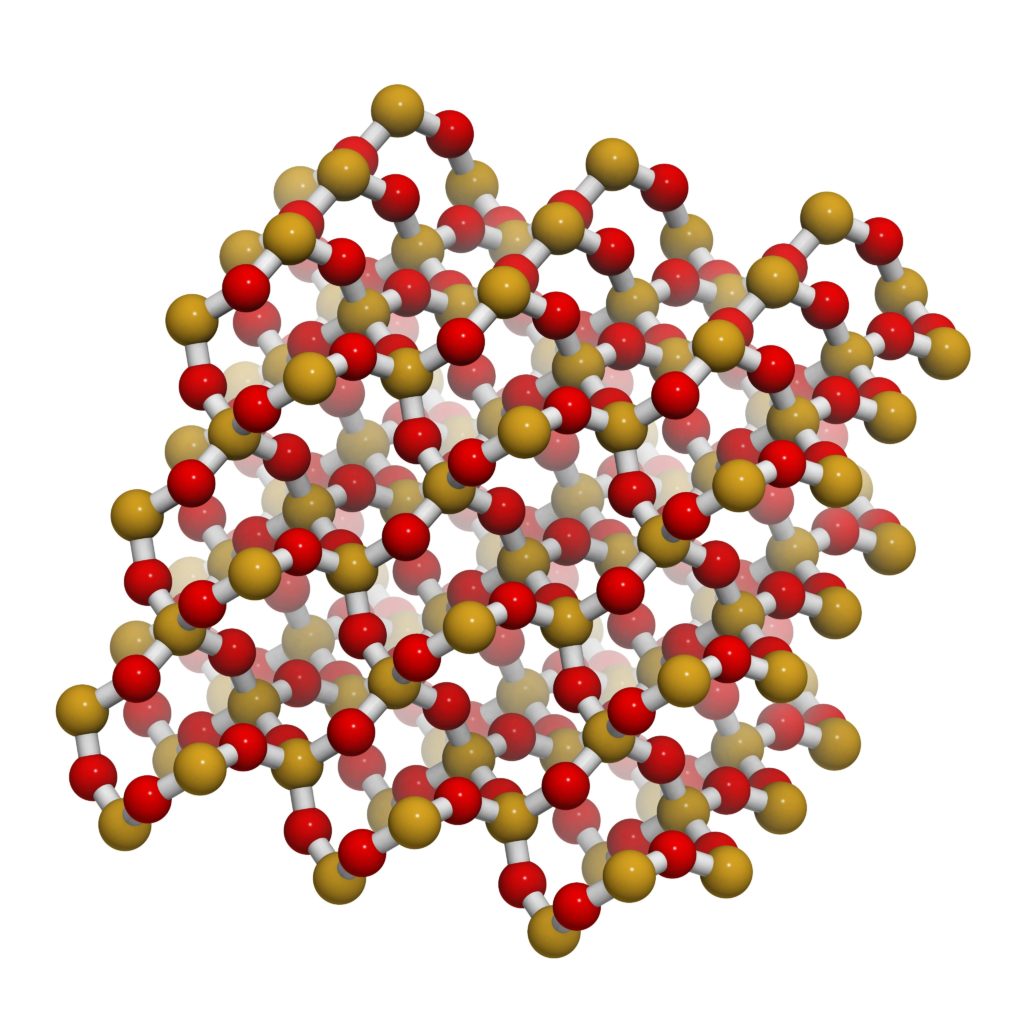

A rock is a natural composition of one or more minerals. A mineral is a naturally occurring, inorganic solid with a defined chemical composition and an ordered atomic structure. For example, quartz is a mineral with a chemical composition of silicon dioxide, SiO2, with the silicon (yellow) and oxygen (red) atoms ordered in a regular arrangement as shown below.

The term stone refers to a rock or mineral that has been subjected to human handling or use, such as in the technique of pietre dure, or more generally the inlay of hard stones into decorative compositions. The stones in the Courtauld’s baroque pietre dure frame are all the product of a geological process known as mineralization: the infiltration of silica-rich fluids through the cracks, fissures and cavities in solid rock. When cooled, these fluids solidify, precipitating crystals.

In order to accurately identify a stone, it is necessary to identify its constituent minerals. Amongst the physical properties used to distinguish minerals, only several can be observed non-intrusively: colour, lustre and transparency (see below). Other mineral properties include hardness, cleavage, fracture and streak, although these can only be investigated using intrusive techniques.

Colour

The mineral lazurite is always blue. However, some minerals can form in a variety of colours due to the inclusion of different chemical impurities, known as trace elements, in their atomic structure. For example, pure quartz or rock crystal is colourless, but it can also appear pink or red with the inclusion of iron in different states of oxidation. One such case is purple amethyst, which includes traces of Fe3+.

Lustre

The word ‘lustre’ describes the way in which light reflects off the surface of the sample of mineral or rock. This is a visual scale, whereby the surfaces of minerals can be described using terms such as ‘metallic’, ‘vitreous’ (glass-like), ‘waxy’, ‘dull’ or ‘adamantine’ (diamond-like).

Transparency

The transparency of a mineral describes the amount of light able to pass through the sample. It is classified into three categories: ‘opaque’, which allows no light through; ‘translucent’, which allows some light through; and ‘transparent’, which allows all of the light through.

Decorative Stone Identification

Identifying decorative stones, such as those used in The Courtauld Gallery’s pietre dure frame, may be one of those instances where scientific investigation is inappropriate. While geologists use destructive analytical techniques to accurately identify rocks and minerals from the field — smashing them open or finely slicing them to view under a microscope — these methods are not an option when considering valuable and historically important objects from a museum collection.

Moreover, even some non-intrusive techniques are not particularly useful for decorative stone identification. Most analytical techniques, such as X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) and Raman spectroscopy, provide information on either crystal structure or chemical composition. However, many materials that look very different may have essentially the same chemistry. For example, glass, quartz, amethyst, agate and jasper are all composed of silica (SiO2). Therefore, chemical techniques can tell us what a stone is, but can rarely tell us where it came from.

These limitations mean that decorative stones are usually identified by a combination of observation, connoisseurship and comparison with other stones of known provenance. An excellent resource for identifying decorative stones is the extensive Corsi collection. Composed of exactly 1000 polished stone slabs of uniform shape and size (145 x 73 x 40 mm), the collection was established by the Roman lawyer Faustino Corsi (1771–1846) by the first quarter of the 19th century and is now housed in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History.

Lapis Lazuli

Lapis is the Latin word for ‘stone’. Lazuli originates from the Persian word lazhuward meaning ‘blue’, and the Arabic word lazaward meaning ‘sky’. This rock is composed primarily of the minerals lazurite, pyrite and calcite. Pyrite has a metallic lustre, whereas calcite and lazurite have sub-vitreous lustres. All three minerals are opaque. Lazurite gives lapis lazuli its characteristic and highly prized blue colour, pyrite appears as golden flecks, often referred to as ‘the stars in the sky’, and calcite is present as white veins running throughout the rock. The more calcite in the chemical composition, the whiter the rock and the less valuable it is.

The highest-quality lapis lazuli is most commonly mined from Sar-e-Sang in the Badakhshan region of northern Afghanistan. It has been sourced there for over 6000 years. Nowadays, lapis lazuli quarries can also be found in the banks of Russia’s Slyudyanka and Malaya Bystraya rivers, as well as Lake Baikal.

Due to its intense blue colour, lapis lazuli has been extensively used for decorative purposes since antiquity. For example, the ancient Egyptians used it to embellish sacred objects, and the Babylonians shaped it into beads for adornments.

Lapis Lazuli for Pigment

Lapis lazuli was also widely used in Medieval and Renaissance paintings as a deep blue pigment known as ultramarine. For example, it was used to paint the blue clothing in Ortolano’s (fl. 1500–after 1527) Woman Taken in Adultery, of 1524–27, which is displayed near to the display case for our frame in The Courtauld Gallery.

In his celebrated craftsman’s handbook, Il Libro dell’Arte, Cennino Cennini (1360–1427) describes many different methods and techniques used in painting and decorating surfaces. Included in this manual is a detailed explanation of the long and arduous process required to prepare ultramarine pigment from rough lapis lazuli rock. Cennini’s admiration for the hue is evident in his claim that “ultramarine blue is a colour illustrious, beautiful, and most perfect, beyond all other colours; one could not say anything about it, or do anything with it, that its quality would not still surpass.”

A full version of this account, entitled On the Character of Ultramarine Blue, and How to Make it, can be found here.

Agate

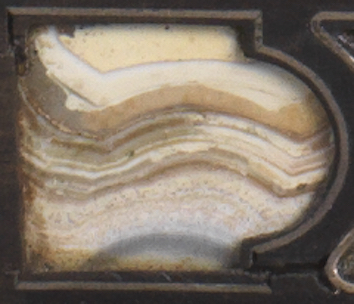

Agate is a variety of quartz, characterised by its concentrically banded appearance. Banded agate forms by the permeation and build-up of layers of silica in cavities within rocks. It is frequently found in basalts. The silica solution separates into layers, some containing water and others without, resulting in the distinctive concentric bands.

Agates come in a wide variety of colour combinations, almost all of which are a result of the inclusion of iron oxides in its chemical composition. Agate can range from opaque to transparent and has a vitreous lustre. Several varieties were used as inlays on The Courtauld’s opulent frame, as seen in these images.

Whilst agate is now found commonly worldwide, Germany has long been one of the best-known historic sources of agate with over 50 quarries in and around the famous lapidary (stone-cutting) workshop of Idar-Oberstein. Situated on either side of the fast-moving Nahe river, Idar-Oberstein became one of the main stone-cutting centres in the late 15th century, since the high-powered water provided enough energy to turn the large sandstone grinding wheels that were up to 3.3m in diameter.

Agate has been valued for its hardness as well as its decorative properties, with uses including polishing gold. Small hand tools with differently shaped agate tips have been used for burnishing gold leaf for centuries up until the present day.

Amethyst

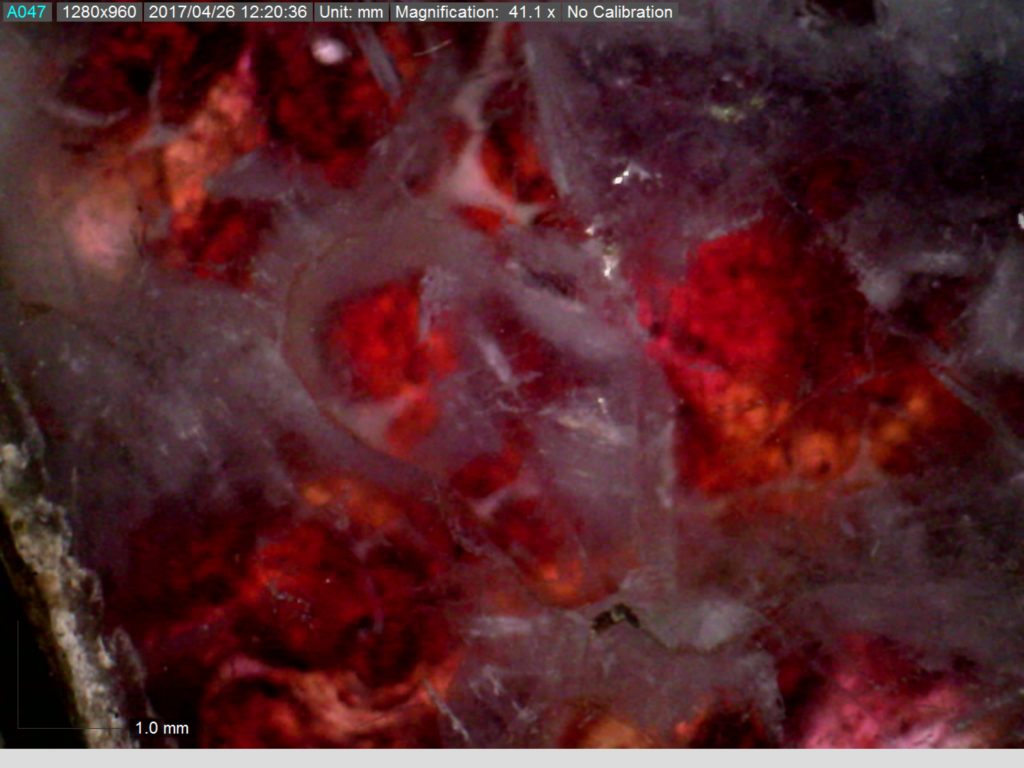

Amethyst is a purple variety of quartz. Its regal colouring appears in a range of hues, varying from light lilac to deep indigo depending on the abundance of iron in its chemical composition. It has a vitreous lustre and is translucent.

Amethyst often grows along the inner walls of hollow igneous rocks, known as vesicles. Vesicles are produced by bubbles of gas in magma or lava creating cavities in the rock when solidified. Small cracks in these rocks allow for liquid silica to seep in, which then precipitates crystals of amethyst.

During the 17th century, when this frame was made, amethyst was found in a multitude of European sources, particularly in Bohemia and the Black Forest. It then would have been sold to the famous lapidary workshops of Idar-Oberstein for cutting and polishing.

Nowadays, the largest commercial sources of amethyst are Brazil, Uruguay, Siberia and North America. The largest amethyst geode (a rock cavity lined with crystals or other mineral matter) in the world is the Empress of Uruguay, which reaches 3.27 metres in height and weighs over 2.5 tonnes.

Sicilian Jasper

Referred to as diaspri di Sicilia in Italian, Sicilian jaspers are very hard and occur in a multitude of colour and pattern variations, making them ideal stones for ornamentation. Today they are no longer commercially quarried, but around 300 varieties of Sicilian jasper have been identified in the Baroque churches of Sicily. Reaching their heyday in the 17th and 18th centuries, Sicilian jaspers were mined mainly in the province of Palermo, particularly near the towns of Giuliana and Bisacquino.

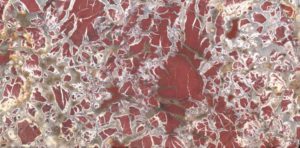

Jasper is a variety of opaque cryptocrystalline (the crystals cannot be seen, even under a microscope) quartz formed by silica-rich fluids percolating through fissures in limestone rocks. They come in an abundance of colours, with the red variations attributed to the presence of hematite and yellow to the presence of goethite. Brecciated jasper, which has a fragmented appearance, has formed due to movements of the rock, perhaps triggered by earthquakes. Like agates, jaspers can range from opaque to translucent and have a vitreous lustre.

Thanks to the comprehensive Corsi collection mentioned above, it is possible for specialists to identify varieties of Sicilian jasper used on decorative pieces. Present in The Courtauld’s baroque frame are inlays of diaspro di Palermo, which is a brecciated jasper with orange, red and colourless fragments (see Corsi 776 below), and two types of diaspro di Giuliana, one of which is a brecciated red jasper with rims of opaque white quartz (see Corsi 745 below), the other being a banded version of yellow and green layers (see Corsi 764 below).

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr Ruth Siddall, Senior Lecturer in Earth Sciences at UCL, and Monica Price, Collections Manager at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, for their invaluable expertise in decorative stone identification, their continued guidance and their generosity in lending us rock and mineral samples from their collections for the display. I also wish to thank the following scholars for their time and knowledgeable insight: Professor Aviva Burnstock, Professor and Head of the Department of Conservation and Technology at The Courtauld Institute of Art; Silvia Amato, PhD student and Technical Assistant at The Courtauld Institute of Art; Graeme Barraclough, Chief Conservator at The Courtauld Gallery; Matthew Thompson, Gallery Technician at The Courtauld Gallery; Dr Emma Passmore, Senior Teaching Fellow in Earth Sciences at Imperial College London; Nadine Gabriel, MSci Geology student at UCL; the furniture historian, Simon Jervis, as well as the frame historian, Lynn Roberts.

Bibliography

Bonewitz, Ronald Louis. Rocks & Minerals: The Definitive Visual Guide, 2nd ed. London: Dorling Kindersley Limited, 2008.

Cennini, Cennino. The Craftsman’s Handbook : The Italian “Il Libro Dell Arte”, trans. Daniel V Thompson Jr, 1st ed. New York: Dover Publications, 1960.

González-Palacios, Alvar. ‘Concerning Furniture: Roman Documents and Inventories’. Furniture History, Vol. 46 (2010): 1–135.

Koeppe, Wolfram, and Annamaria Giusti. Art of the Royal Court: Treasures in Pietre Dure from the Palaces of Europe. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008.

Pabian, Roger K., Brian Jackson, Peter Tandy and John Cromartie. Agates: Treasures of the Earth. London: Natural History Museum, 2006.

Price, Monica T. Decorative Stone: The Complete Sourcebook. London: Thames & Hudson, 2007.

Price, Monica T., Lisa Cooke. ‘Corsi Collection of Decorative Stones’, accessed 12 June 2020, http://www.oum.ox.ac.uk/corsi/

Swynfen Jervis, Simon. ‘Review of Arredi e Ornamenti alla Corte di Roma by Alvar González-Palacios’. The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 148, No. 1239 (2006): 422–23.

worked on this project during her MSc in Science Communication at Imperial College, London.