We’ve been busy working on our dissertations, so we’re taking the opportunity to get to know the current MA Documenting Fashion students. Here, Claudia discusses Ossie Clark, military peacocks, and what artists wear.

What is your dissertation about?

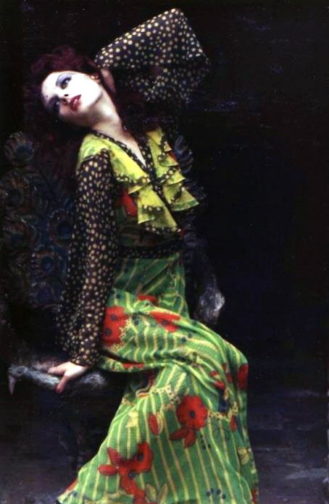

My dissertation centres around how temporality and nostalgia manifested in the designs of Ossie Clark and textile designer Celia Birtwell during the retro-mania of the late 1960s and early 1970s. From his seductive, transparent garments (often worn without underwear) to his hyper-feminine bias cut dresses, Clark was able to reflect contemporary notions of progressive female sexuality whilst simultaneously referencing past art movements and designers. Ranging from the Pre-Raphaelites to 1940s fashion, Clark and Birtwell’s past influences also translated into the fashion photography of their collaborative creations.

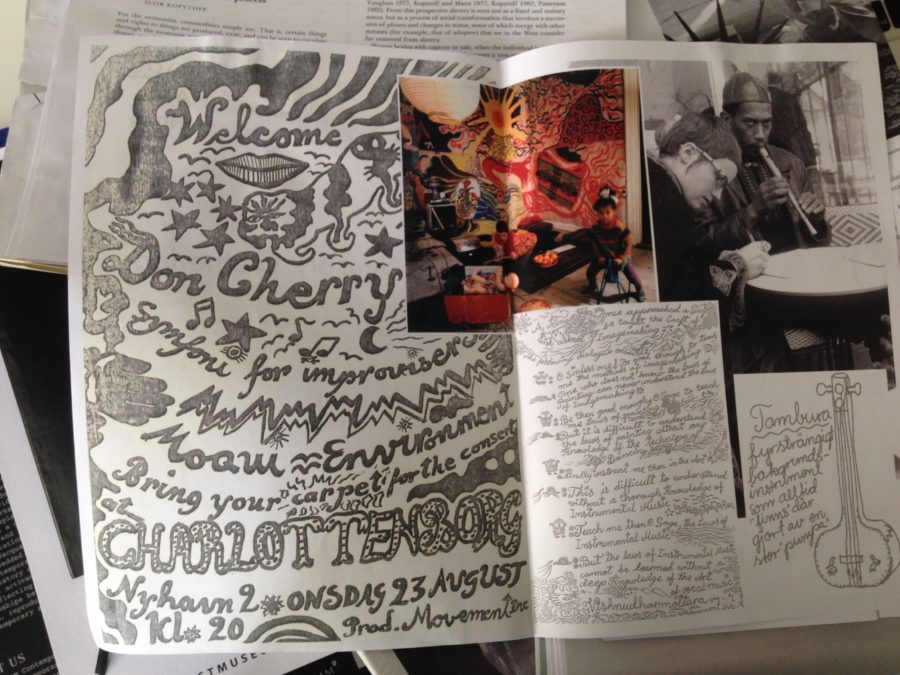

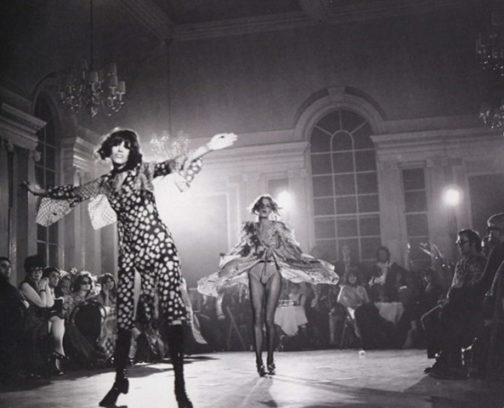

My virtual exhibition also focused on Ossie Clark, where one section, ‘Modern Retro’, sought to display the influence of history on Clark and Birtwell in an era of self-conscious modernity. I based my exhibition in Chelsea Town Hall, where Clark held some of his theatrical and often shambolic fashion shows. By the end of the project, I could really visualise the space and how the exhibits (and my imaginary visitors) would interact with each other.

I wanted to convey the impression of an immersive, multi-sensory experience, where people could flow freely through the space. My visitors would be given headphones which would react to each display, playing music to coordinate with each exhibit. I hoped to create a solo, silent Ossie rave to help transport visitors to Swinging London. Having scratched the surface in my virtual exhibition, it’s been really interesting delving deeper into themes of history and continuity in my dissertation research.

What is your favourite dress history photograph?

To save this from turning into an Ossie Clark rant, I’ll opt for one of Horst P. Horst’s neoclassical images, featured in Vogue from September 1937. The model, adorned in a silvery gown by Madeleine Vionnet, seems to simultaneously embody a classical goddess and a modern woman. Posed to statuesque perfection, her bejewelled wrists, held above her modestly lowered head, are clasped together like the fastening of a necklace, metamorphosing her iridescent body into a precious pendant. Alternatively, the vertical pleats of her dress could also transform her into a Corinthian column. The outline of her thigh shimmers under the studio lights, hinting at the sensual body beneath. I love how tactile this image is. Just from looking at it, we get a sense of exactly what it would feel like to wear this dress and to have each delicate pleat ripple across the body.

What is your favourite thing that you’ve written/worked on/researched this year?

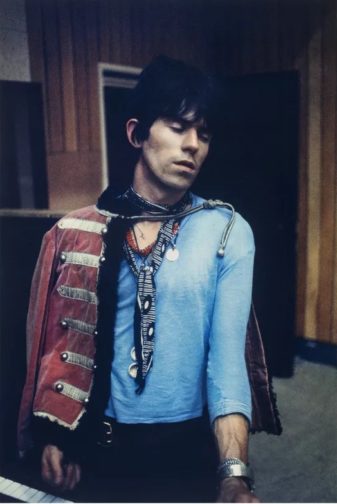

I really enjoyed my essay on how military uniform was appropriated by The Rolling Stones and The Beatles in 1966 and 1967. The fact that such archaic and hyper-masculine garments were incorporated into progressively androgynous, peacocking menswear reveals an interesting point of tension in regards to modernising masculinity. The Beatles and The Stones arguably brought this counterculture style of dress to the forefront of contemporary consciousness, asserting their flamboyant individuality, which, ironically, created an impression of uniformity within, and between, both bands.

What is your favourite thing you’ve read this year?

Charlie Porter’s What Artists Wear is something that I keep coming back to (mainly just to flick through the pictures). Porter highlights how the physical intimacy of clothing offers a more personal perspective on world famous artists, from Louise Bourgeois wearing her own latex sculptures, to Frida Kahlo’s politically-charged adoption of, and self-documentation in, men’s suits. I enjoyed how Porter centres debates around female artists’ bodies, which have been historically restricted by clothing. Dress has the destructive potential to limit bodily autonomy and, by extension, creative output. Yet, at the same time, dress becomes a canvas on which artists express themselves, a means to connect with viewers of their work, as well as autobiographical evidence of their life. It really makes you question what you choose to wear.

What are you wearing today?

I wish I was wearing my Anna Sui charity shop find (it’s either a short dress or long top, the jury is still out). Sui is an admirer of Ossie Clark’s work, and the clashing purple floral patterns could have been inspired by Celia Birtwell’s prints, and the flowy sleeves and handkerchief hem are quite Ossie-esque. It’s been fun wearing this to get into character to write my dissertation. I would have worn it over mauve flares, also from a charity shop, and my pistachio-green cowboy boots, you guessed it, from Shein. I jest. They’re from Oxfam.

What I’m actually wearing is an old Breton-striped top of my mum’s which is literally falling apart at the seams, old baggy shorts, and a straw cowboy hat. I look like a distressed, marooned gondolier. For context, I’ve been hacking away at my dissertation in the garden, not that that excuses my dishevelled appearance. Oh, and I’m also sporting some men’s clogs that have become communal gardening shoes. My tortoise is affectionately head-butting one clog as the opening act of his mating ritual. Aside from that, he’s been a very devoted research assistant. He’s wearing his custom-made tortoise-shell print shell suit which I’ve never actually seen him take off…

By Claudia Stanley

Please join us Friday 29 June, 2018 at the Courtauld Institute of Art 10:30am-12:00pm for a live recording of The Conversations with Jason Campbell & Henrietta Gallina podcast, open to all free admission

Please join us Friday 29 June, 2018 at the Courtauld Institute of Art 10:30am-12:00pm for a live recording of The Conversations with Jason Campbell & Henrietta Gallina podcast, open to all free admission