This post contains spoilers from the film Passing.

Jazz, novelty, dynamism and the rebirth of Black culture… It was the 1920s and the Harlem Renaissance was in full swing. Mainly taking place in New York and spreading to the rest of the world, the era spanned from the 20s to 30s and beyond. However, behind the glitz and glamour was an era tainted by prohibition and racial tensions. An esteemed product of this age, which captured the psychology, and tensions of the era subtly yet brilliantly, was Nella Larsen’s novel Passing (1929), recently adapted to a Netflix movie in the same name, by Rebecca Hall as her directorial debut.

Larsen’s story is centred around the encounter of two childhood friends, light skinned, mixed race African-American women, Irene Redfield (played by Tessa Thompson) and Clare Bellew (played by Ruth Negga), in Harlem, as adults and the tensions that rise between them. The twist of the story is introduced when the two women run in to each other at a fancy tearoom at the Drayton Hotel in New York, mostly reserved for wealthy, white upper classes. As it is revealed that Clare is married to a racist, upper-class white man from Chicago, who is however oblivious to her race, it becomes clear that she is ‘passing’ as white because of her light skin tone.

Irene is a middle-class, responsible housewife and mother living in Harlem with her black, doctor husband Brian and two boys. She is fervently tied to her race and community, head of the ‘Negro Dance Committee’ and centres her life around trying to do ‘the right thing’. On the surface she is reserved and abides by morals and class boundaries. Clare on the other hand is reckless, selfish, and passionate, living her life on the edge. However, both characters are intricately complex, juggling with tensions within. Clare denies her roots, yet she also yearns for a sense of community, longs to go back to her own culture, and thus gradually seeps into Irene’s life. While Irene is angry at Clare for denying her race, for her insistence and success at getting what she wants no matter the cost and her relentless challenging of the status quo, she is drawn to Clare and her mystery. Her desire to adopt Clare’s ease and allure makes her unable to drive her out of her life.

Hall lifts Larsen’s words and creates a film that conveys her spirit, and feelings through incredible symbolism. She foreshadows events through objects, accentuates the characters’ distinctive personality traits through clothing, conveys the tension and drama between the figures through dramatic camera shots and music.

Larsen tells the story from the point of view of Irene, so events are mostly tinged by her feelings in the book. Irene’s internal angst which comprises the base of the novel, is poignantly picked up in the film through close-up shots that focus on her facial expressions. Her frustration is amplified through the black and white lens the film is shot in, the chiaroscuro effect that seems to sharpen when Irene is on screen, lighting one side of her face while casting the other side in stark darkness.

On the other hand, Clare, who is constantly described as a ‘vision’ or having a ‘glowing’ sense of beauty in the book, is bathed in a soft light, devoid of the shadows seen on Irene’s face, bringing the glow that surrounds her to Irene’s surroundings, which are often darkened.

At the beginning of the film when Clare and Irene first encounter one another, the close-up shots distinctly switch from one woman’s face to the other. This technique is repeated later when Clare comes to Irene’s house for the first time. Hall amplifies the fact that the two women are in fact mirrors but also complete one another.

Although the scene in the beginning where Clare is revealed to be married to a racist man and hiding her identity sets the tension of the film, the film is overall devoid of any overt scenes of violence related to racism. Instead, racial tensions that are boiling underneath, are conveyed through secondary sources. In one scene, Irene hears from Brian that one of her sons were called a ‘negro’ at school and in another Brian reads about a black man being lynched on the streets of New York, on the newspaper. Even Clare’s husband John’s prejudice is based on what he has read and heard about black people on the news rather than a personal experience, as it is revealed when Clare introduces him to Ruth at the very beginning of the film.

The film’s high symbolism translates to many elements being conveyed implicitly rather than blatantly. Irene who suspects Clare to be having an affair with her husband, sees them having an intimate conversation through the mirror in the living room in her house, however as she approaches them, the camera then pans right, revealing them to be standing further apart from one another, hence conveying Irene’s growing doubts and jealousy that also cloud her judgement through the symbol of the mirror.

The crack in Brian and Irene’s bedroom ceiling becomes a metaphor for the crack in their marriage which progressively grows as Irene’s suspicions regarding her husband and Clare having an affair deepens as the film progresses. The viewer is presented with individual shots of the couple gazing at that crack, mostly after they have a discordance, in different points of the film. The symbolism becomes more potent as Irene’s marriage becomes turbulent.

In another scene, just as Clare declares her longing to become part of the black community again, Irene drops her flowerpot out the window which symbolises her unease and reluctance in Clare’s sudden intrusion in her life.

The palpable tensions between the women are also conveyed through a jazz piece titled The Homeless Wanderer that is repeated constantly in the film. The piano piece is a fluctuating one, harbouring a sense of melancholy, mystery, and an uneasiness, conveying the feeling of 1920s New York poignantly. However, this melody also mostly fills the intervals, repeated each time when Irene is seen walking home carrying groceries, passing the same brownstone buildings, or after a scene when Clare and Irene have an impactful conversation. On one side it emphasizes the monotony of Irene’s life. On the other, the piece becomes a metaphor for the masks both characters are carrying, the tentative balancing act they perform in keeping secrets, hiding their true selves. It becomes the voice of both characters, speaking what is unsaid, conveying feelings unexpressed.

The drama created through this music, the acute camera angles, and the sharp chiaroscuro emanates a Hitchcockian vibe in the film. The tensions rise as Clare increasingly infiltrates Irene’s life. With each move, gesture and gaze, the drama created through the music, the acute camera angles and sharp chiaroscuro carefully calculated by Hall, each scene becomes a perfect composition that reminds one of the theatrical and dramatic nature of the films of the 1920s and 1930s as well as American film noir. The drama, compressed feelings and tensions become even more amplified in the boxed, 4:3 ratio frame the film is shot in. The usage of black and white cinematography, while on the on side evoking the film style of the era, it more importantly, draws attention to the idea of race and skin colour. The idea of ‘passing’ is very clearly visualised as it becomes difficult to distinguish the skin colour of the two women from white men. It is an ingenious technique, in which Hall stated that she employed to draw the attention to the concept of race and its construction by the powerful figures in society to serve their needs while the fact in the matter is, the complex nature of race cannot be simplified and boxed into a category. She says: “After all, black and white film is not black and white, it’s a thousand shades of gray, just like everything else.”

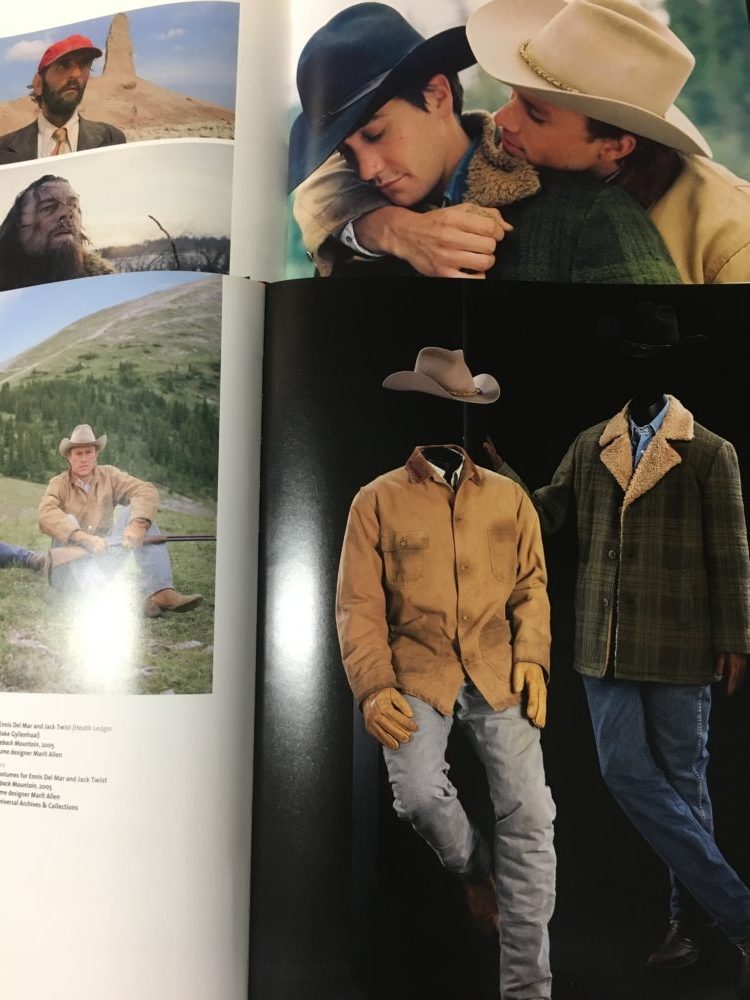

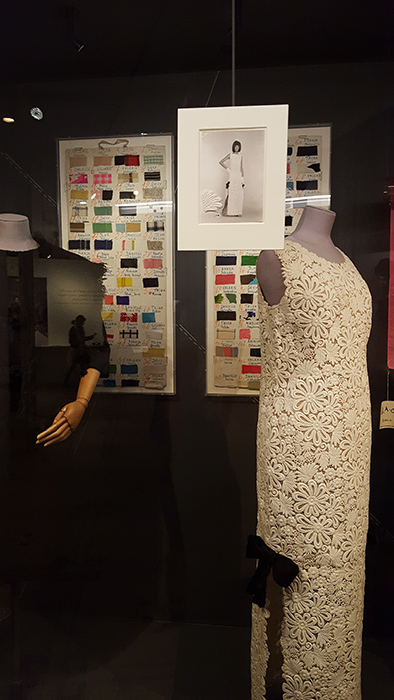

The film becomes a distinct character study. The one aspect sacrificed for the black and white lens is the incredibly vibrant and colourful dresses of characters that are drawn specific attention to in the book. Instead, the two women’s identities are constructed through their silhouettes, the style of their dresses and more specifically, by their hats.

Irene, from the very beginning of the film enters the scene with a brimmed hat that covers half of her face. Throughout the film, she rarely goes out without a brimmed hat. The hat indicates Irene’s closed off nature and her reserved manners. It becomes much like a shield that she hides behind to protect herself from the rest of the world and to hide her race. This is further accentuated by her slumped posture and her modest, conventional outfits that mostly cover her shoulders. Even when she wears an evening gown with straps that exposes her shoulders, she wears gloves that cover more than half of her arms, always shielded from contact with outside world. Contrastingly, Clare rarely wears a hat. The ones she wears occasionally, always reveal her face. Her upright, firm posture is accentuated through her outfits that always seem to have bold shoulders. Whether it’s an evening gown, a coat, or a day dress, they stand out distinctly either through their cutting, the pattern of the fabric or embellishment, emphasising her strong stance, her confidence despite her precarious position. Although Clare is the one at risk ‘passing’ as white, it’s Irene who hides behind her hat, concealing her identity. The clothes distinctly stand in for the characters themselves.

Perhaps the film’s most striking scene comes towards the middle when Irene and Clare are out at the dance organised by the ‘Negro Dance Committee’. Irene makes a comment whilst observing Clare dancing, from the corner, saying: “We’re all of us passing for something or other. Aren’t we?” She condones Clare yet she undeniably envies her as she reminds her of her own inability to be reckless. Clare’s desperate, incessant, and fierce attempts to go back to her roots and immerse herself in her own culture, reminds us of the inevitability of the illusion of pretence fading, as the innate desire to be true to oneself surfaces which Clare quite unapologetically reflects. Both characters, on the surface, seem to belong to distinct categories. However, as both characters yearn for the position of the other, it is revealed that those categories are society’s circumstantially imposed labels. The story shows the consequences of living in a society were racism looms large, hiding one’s identity to ‘pass’ as something that is acceptable by the society.

The story struck a personal chord with Hall whose mixed-race grandfather had ‘passed’ as white in 30s. The making of the film became a cathartic experience for Hall as she described the process illuminating and clarifying regarding her own past and decent.

The film underlines Larsen’s idea, that the concept of ‘passing’ is not specific to an age or a race in its core but rather how people everywhere, at every age, at one point or another comply with society’s desires, rules, and beliefs to blend in, to ‘pass’. Yet it also shows the misery this creates and its unsustainable nature as it goes against human nature to be free.

Both Thompson and Negga give superb performances, breathing life to Larsen’s complex characters, conveying feelings of frustration, yearning and desire through mere glances. With nostalgic costumes, the jazz music that plays over shots of brownstone buildings of the city, the dramatic close-ups and the chiaroscuro effect, Hall captures the spirit of a bygone age, transporting us back to New York in the 20s.

Passing is streaming now on Netflix

By Ipek Birgul Kozanoglu

Sources

Larsen, Nella, Passing, Signet Classics, 1929

https://www.history.com/topics/roaring-twenties/harlem-renaissance

https://www.britannica.com/event/Harlem-Renaissance-American-literature-and-art

https://www.goldenglobes.com/articles/rebecca-hall-bows-passing

https://www.goldenglobes.com/vertical-gallery/passing-vibrant-shades-grey

https://www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2021/11/netflix-passing-rebecca-hall/620651/

https://www.digitalspy.com/movies/a38207513/passing-review-netflix-tessa-thompson-ruth-negga/

https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/awards/story/2021-11-23/passing-ruth-negga-rebecca-hall

https://www.indiewire.com/2021/10/passing-rebecca-hall-interview-1234674475/