Hadi Safaeipour

Orbelian’s Caravanserai (Armenian: Օրբելյանների Քարվանսարա; formerly known as Sulema Caravanserai and Selim Caravanserai, Armenian: Սելիմ), is a caravanserai in the Vayots Dzor Province of Armenia, known as the best preserved caravanserai in the entire country and as an excellent example of Armenian secular architecture from the Middle Ages. It lies below the road just before the summit on the south side of Selim Mountain Pass (presently known as Vardenyats Mountain Pass), to accommodate weary travelers and their animals as they passed along the international trade route connecting with Lake Sevan. The caravanserai points north to Vayots Dzor and south towards the mountainous lands in Iran.

This monument, built by Prince Chesar Orbelian and his brothers in 1332 during the reign of Abu Said Khan II, played an important role in this region thanks to its location on an international trade route and to the character of Orbelian patronage. The Orbelians were a major feudal family in Georgia throughout the twelfth century. In 1177/8, their leader Ivane led his extended family into a power struggle between the deceased king’s young heir, Demetre, and the king’s brother Giorgi. Ivane’s son Elikum became an important official, converting to Islam and dying in one of the Persian atabek’s wars. He left behind a young son and a widow, the sister of an Armenian bishop of Syunik, who was forcibly married to a Muslim notable in Nakhchivan. This background allowed the Orbelians to play a mediatory role among the lands of Armenians, Georgians, and Persians as well as Christian and Muslim territories.

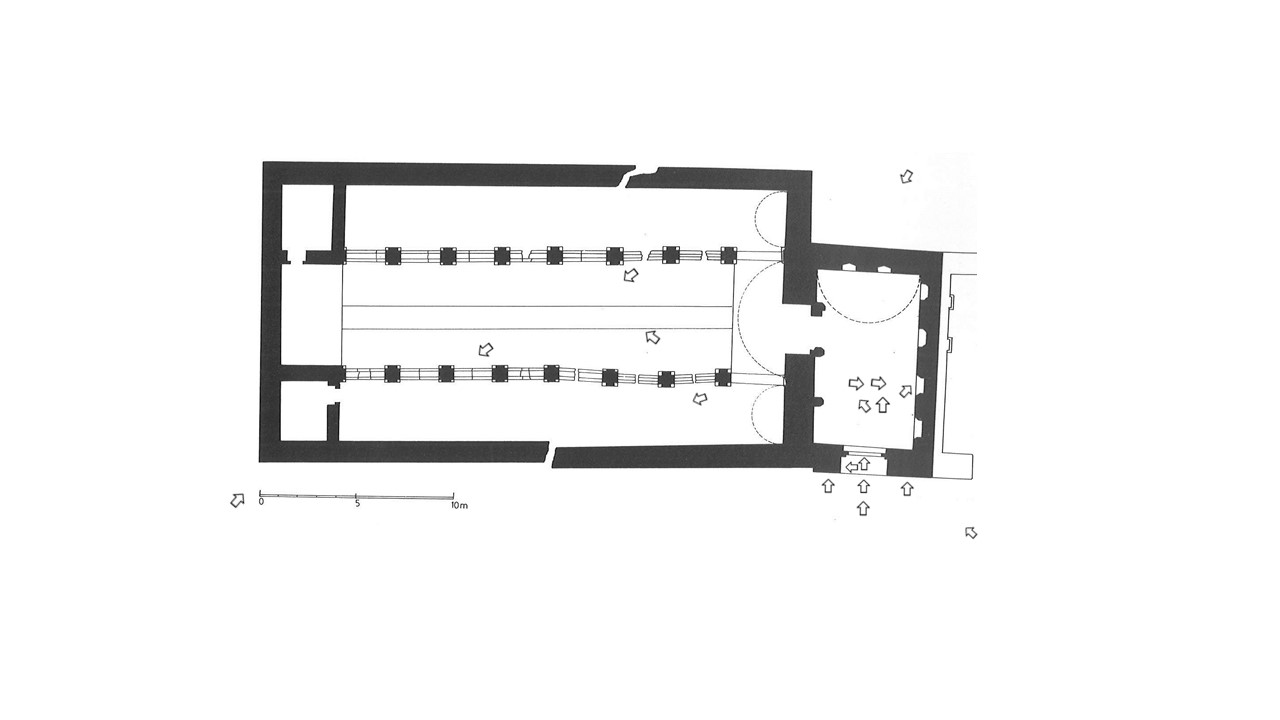

Unlike Anatolian caravanserais such as Karatay Han and Kayseri Sultan Han, the Selim caravanserai does not include a courtyard area, and the whole building is limited to the covered spaces including a large hall, which stretched from east to west, and a vestibule at the western end. This building adapted the caravanserai type to the harsh snowy and windy weather of mountainous lands and suited to the building’s location. This architectural pattern is also applied to the surviving Seljuq caravanserais in the mountainous lands of this region. The Nir-Pass Caravanserai, for instance – located by the route that connects Tabriz to Ardebil in Iran – is one of the Seljuq buildings which comprise covered spaces. The only entrance (1.65 x 2.0 m) to the hall of Selim Caravanserai is from the adjacent vestibule, a rectangular room (5.35 x 9.0 m) covered with a gabled shingle roof resting on three arches. On the east these arches rest on the window edges; on the west on polyhedral pillars.

The southern wall of the vestibule and the entry wall façade are among the few ornamented elements of the caravanserai. The entry façade consists of sparsely decorated walls and an ornate gable that are separated by a tree-tier muqarnas cornice. In the centre, the doorway is surmounted by a half-rounded lintel upon which a Persian inscription, now almost effaced by vandals, gives the date of 1326‑7. The whole façade is crowned with a six-tier muqarnas vault next to which are placed images of a lion to the left, and a bull to the right. There is another inscription written in Armenian at the eastern interior wall of vestibule, which in contrast with the Persian one is legible and reads the following:

In the name of the Almighty and powerful God, in the year 1332, in the world-rule of Busaid Khan, I Chesar son of Prince of Princes Liparit and my mother Ana, grandson of Ivane, and my brothers, handsome as lions, the princes Burtel, Smbat and Elikom of the Orbelian Dynasty, and my wife Khorishah daughter of Vardan [and …] of the Senikarimans, built this spiritual house with our own funds for the salvation of our souls and those of our parents and brothers reposing in Christ, and of my living brothers and sons Sargis, Hovhannes the priest, Kurd and Vardan. We beseech you, passers-by, remember us in Christ. The beginning of the house [took place] in the high-priesthood of Esai, and the end, thanks to his prayers, in the year 1332.

The hall is divided into three naves by seven pairs of pillars. At the end of the narrow aisles on the western side, small rooms were built for the men accompanying the caravan. The animals of the caravan were kept in the hall’s narrow aisles, where stone troughs were built between the pillars and where a pool of water could be found in one of the corners of the hall. The roof of the three-aisled hall is covered by means of three parallel vaults, with that above the central aisle being taller and wider than those of the two lateral aisles. The vaults are supported by arches stretching from pillar to pillar (in the central aisle) and from the pillars to the walls (in the side aisles). Oculi placed in the middle of three of the vaults served the purpose of letting in sunlight and fresh air, while also letting out smoke. Each oculus is decorated with a two-tier muqarnas cornice. These are the only other areas of the caravanserai that carry ornamentation besides the decoration found at the entry vestibule. The caravanserai was restored during the years 1956-1959. Ruins of a small chapel are still visible next to the vestibule, across the road from a spring.

Interactive Plan

Image Gallery

Bibliography

- 3dwarehouse. (2016, Jun 14) Selim Caravanserai. Retrieved from https://3dwarehouse.sketchup.com/model.html?id=dfd74b72d1b433a24f28170dea196580

- Kiesling, Brady & Kojian, Raffi. 2005. Rediscovering Armenia: Guide (2nd ed.). Yerevan: Matit Graphic Design Studio.

- Kleiss, Wolfram & Mohammad Youssef Kiani. 1983. Karevansara-haye-iran (Trans: Iranian Caravanserais), vol. 1. Tehran: Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization.

- Lane, George. 2009. Genghis Khan and Mongol Rule. U.S.A: Hackett Publishing.

- Orbelian, S. 1859. History of Sisakan Provience. St. Petersburg: Ehhers.

- —-. 1864-66. Histoire de la Siounie par Stephannos Orbelian, 2 Vols, Trans. M. F. Brosset, St Petersburg. Académie impériale des sciences.

- Runciman, Steven. 1988. The Emperor Romanus Lecapenus and his reign: a study of tenth-century Byzantium. U.K: Cambridge University Press.

- Siroux, Maxime. 1944. Les caravansérails d’Iran. Téhéran: De l’Organisation nationale de la protection du patrimoine.

- Thierry, Jean-Michel & Patrick Donabédian & Nicole Thierry. 1989. Les arts arméniens. New York: H.N. Abrams in association with Prelacy of the Armenian Apostolic Church of America-Catholicosate of Cilicia.

- Yavuz, Aysil Tükel. 1997. “The Concepts That Shape Anatolian Seljuq Caravanserais”. Muqarnas, Vol. 14. (1997), pp. 80-95.